« indietro

Measuring the average population densities of plays

A case study of Andreas Gryphius, Christian Weise and Gotthold Ephraim Lessing

di Katrin Dennerlein

Universität Würzburg,

katrin.dennerlein@uni-wuerzburg.de

Abstract:

This paper is about computing the average population density of the stage (average configuration density) for 32 plays of German early modern period. As this value is likely to map the communicative structure of comedies and tragedies it is tested if plays of these genres from Andreas Gryphius, Christian Weise and Gotthold Ephraim Lessing differ significantly in this respect. The results of this case study show promise for investigations in a bigger corpus of German drama of that period. After this first, deductive approach the second one will be inductive. It is about learning what the plays in the quartile with the highest configuration density have in common.

During the last two decades a rise in the use of quantitative, mostly digital methods in writing literary history can be observed. In 1998 Franco Moretti displays the settings and origins of the characters of novels with the help of different kinds of maps in his Atlas of the European Novel 1800-1900 [1]. Coining the term ‘distant reading’ in Conjectures on World Literature in 2000, he elaborates on that concept in Distant Reading (2013) analysing the texts and the metadata of large corpora [2]. In Graphs, Maps, Trees (2005) Moretti points the attention of literary scholars to new forms of visualizing the results of distant reading [3]. In replenishment of the maps already used in his Atlas of the Novel he relies on graphs to compare numbers of novel publications in Japan, France and Italy. Histograms are taken to prove his hypothesis that there are new subgenres of the novel every 25 years. With the help of trees from evolutionary biology he displays canonical and non-canonical aspects of detective novels. While Moretti mostly enlarges the corpora and displays results of traditional questions and investigations in more or less unusual ways for literary history, Stephen Ramsay is drawing on findings which can only be achieved with the help of algorithms in Reading Machines: Toward and Algorithmic Criticism (2011) [4]. A scholar combining the analysis of large corpora and close reading methods of textual analysis is Matthew Jockers. In Macroanalysis he works on a collection of mostly British, Irish and American novels from the 18th and 19th century and relates publication phases to geographical regions [5]. He also moves on to the content by using stylometry, topic modelling and network analysis. With these approaches he shows the influences on Herman Melville’s Moby Dick as well as its outstanding elements, distinguishing it from other examples of the novel of that time [6]. The new digital approaches thus cover all levels of writing literary history: analyses of single works, of (sub)genres, of outliers of a genre and of periods and developments. There is a high awareness of the fact that it is necessary to show the relevance of the analysis of large corpora with regard to traditional approaches in literary criticism, i.e. to mediate between close and distant readings. Jockers, for instance, emphasizes the fact that the results of algorithmic processing are far from being read in terms of simple, direct understanding but are to be analysed thoroughly.

The above mentioned studies on computing literary history are rather broad concerning the methodological approaches and periods of the literary history they cover. At the same time they are quite restricted with regard to the genres they analyze: they all deal with novels. This is why the following paper aims at exploring dramatic texts with digital methods [7]. One computable aspect of high importance to dramatic texts are the encounters of characters on stage in different con stellations. Beyond single encounters of characters it seems to be interesting to look at the average population density of a play to gain insights into its communicative characteristics [8]. As a case study of German drama in the 17th and 18th century this value shall be computed and interpreted for comedies and tragedies of the early modern German authors Andreas Gryphius (1616-1664), Christian Weise (1642-1708) and Gotthold Ephraim Lessing (1729-1781). The results are analyzed first with a deductive then with an inductive approach. At the beginning it is asked if the different communicative structures of comedies and tragedies map distinctive ranges of configuration density. The inductive approach then, is about learning what the plays in the quartile with the highest configuration density have in common and if it leads to new insights investigating those plays together [9].

In 1970 Solomon Marcus propounds the idea of computing dramatic texts with algebraic methods in his book Mathematische Poetik [10]. As a basic value he charts the scenic presence of characters of a play, visualized in a configuration matrix for every single text [11]. The matrix holds one row for every character and one column for every scene. If a character appears on stage, it is registered in the corresponding cell. Based on these matrices Marcus computes for instance, the co-presence of characters, their lack of encounters or their scenic presence over long periods as well as the overall configuration density of a play [12]. The latter is the result of dividing the number of cells holding a 1 by the total number of cells (i.e., the number of characters multiplied by the number of scenes). In other words the configuration density indicates how many of the potential character entrances have actually been realized. It can therefore be designated as a measure of a play’s ‘population density’. If every character appears on the stage in every scene, the play has a maximum configuration density value of 1 but this is a very rare exception.

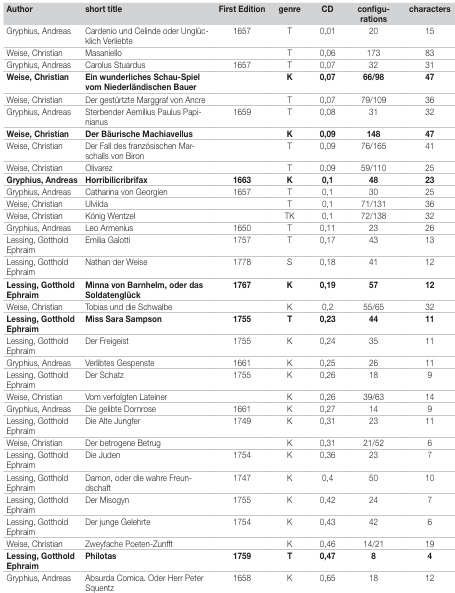

Affiliated research – mostly from the 70s and early 80s – uses Marcus’s mathematical approach for the analysis of two up to a dozen texts [13]. Configuration matrices there prove their usefulness in text analysis because they fasten and simplify the overview of a character’s first or last presence, co-presence or avoidance of other characters [14]. Hartmut Ilsemann takes on the ideas of Solomon Marcus in the 1980s to explore Shakespeare‘s plays [15]. He finds out that the configuration density is one aspect of genre-distinct quantitative patterns for comedies, romances, trag edies and history plays [16]. These findings are the starting point for the following case study in 13 tragedies, 17 comedies, one tragicomedy and one ‘Schauspiel’ of the German authors Andreas Gryphius, Christian Weise and Gotthold Ephraim Lessing (see Table 1). In social sciences a case study is an investigation with few examples which may be studied in detail and in their specific context, usually preparing an extensive study of one aspect with many items [17]. It serves to develop hypotheses for the analysis of large corpora. In the present study the above mentioned authors were chosen for a case study because they fulfill two criteria: they have written several comedies as well as tragedies and, at the same time, are canonical for the literary histories of German drama of the 17th and 18th century [18].

In a first, deductive approach my hypothesis holds that the average configuration density values of the comedies in the corpus are considerably higher than those of the tragedies [19]. This seems fairly plausible given some characteristics of tragedies and comedies already known: Firstly, tragedies more often feature monologues because they provide the ideal occasion to reflect on jealousy, hate and guilt and plans of murder and suicide. A general lack of communication, or communication difficulties, secondly may be associated with the fact that fewer characters feature on stage. In comedy, however, protagonists more often encounter each other. Typical comic effects such as confusions between characters or characters exchanging roles as well as asides, or speeches delivered ad spectators are staged in the presence of several characters and may result in a comparably high configuration density. Thus, the investigations in configuration density are not meant to substitute existing research on those genres but to complement it [20]. It is obvious that genres are not to be reduced to one single aspect but are characterized through a series of characteristics [21].

Before starting there is a structural problem to be solved: the 32 dramatic texts of the corpus show quite different structures with regard to units of the plot [22]. While the plays of Andreas Gryphius do have no subdivision into scenes but are only divided into acts [23], the plays of Weise and Lessing are subdivided into scenes. Nevertheless the last two also show differences in that the scenes of Lessing equal configurations, i.e. stable constellations of characters following the rules of French classicism, whereas in Weise’s plays characters are entering and leaving the stage within scenes. In the case of Lessing every configuration equals a scene whereas a scene of a play by Weise may contain several configurations. As most of Gryphius’ plays have neither scenes nor configurations and as it makes no sense to attribute arbitrary scene division to the plays by hand, the dramatic texts by Gryphius and Weise were subdivided into configurations as well. In other words: every time a character enters or leaves the stage a new configuration has to be stated and the presence of characters noted. As there is no way to do this electronically it was done by hand [24]. Only in the case of Lessing configuration den sities were computed with a Python script evaluating the scene divisions and speaker information already tagged with TEI markup in the electronically available texts [25].

II

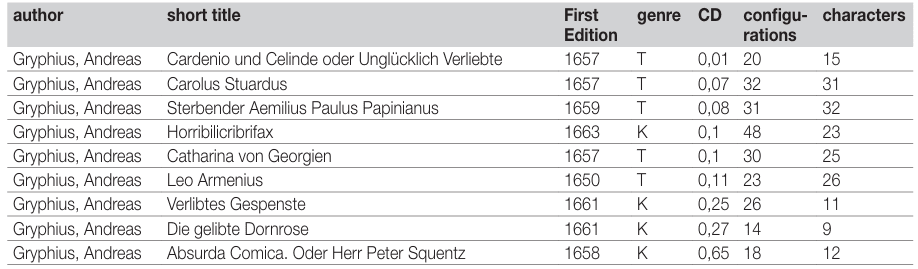

The plays by Andreas Gryphius (1616-1664), premiered between 1650 and 1674 and first printed between 1650 and 1663 show a range of configuration density values from 0.01 to 0.11 for tragedies and from 0.1 to 0.6 for comedies (see table 2). There is a comparatively clear demarcation line between tragedies with configuration densities ≤ 0.1 and comedies ≥ 0.25 with the exception of the comedy Horribilicribri fax Teutsch. It deals with the topic of pretending and being in terms of love affairs, reputation and material goods exemplified in several parallel actions. This entails an episodic structure with sequences of meetings of one character with several counterparts often featuring only two or three of the 23 characters of the play. By the way, this example thus exemplifies the observation of Manfred Pfister that a low configuration density is a hint at an episodic structure [26]. Gryphius’ plays also feature the lowest as well as the highest configuration density values of the whole corpus. The dramatic text with the lowest configuration density by far, the tragedy Cardenio and Celinde (1657), follows the dramaturgy of the Jesuit play in changing different sinful constellations of desire into sudden religious epiphany [27]. It contains four Reyen, i.e. choruses, sang by four different sets of allegorical characters who do not participate in the main action, a fact that lowers the configuration density significantly [28]. The remarka bly high configuration density of Absurda Comica Oder Herr Peter Squentz accounts for the fact that the biggest part of the troupe of Peter Squentz is always on stage, rehearsing and arguing about its performance which is staged in front of the courtly audience dur ing 17 of the 18 configurations. Showing more than half of the dramatis personae on stage in almost all configurations makes the average population density rise up to 0.65.

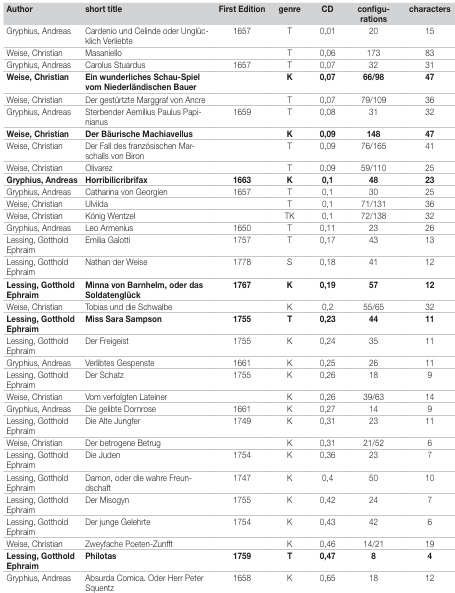

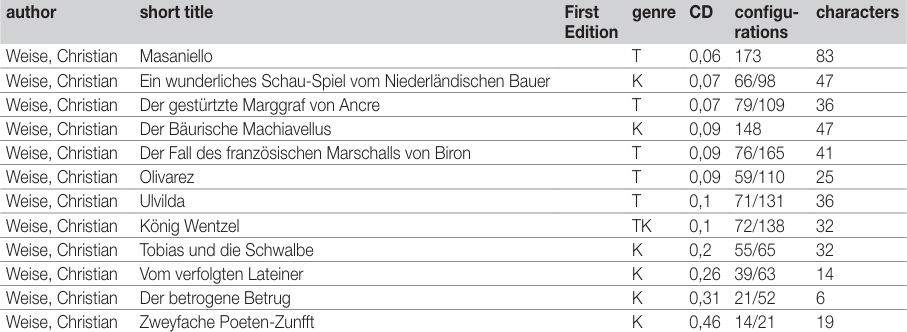

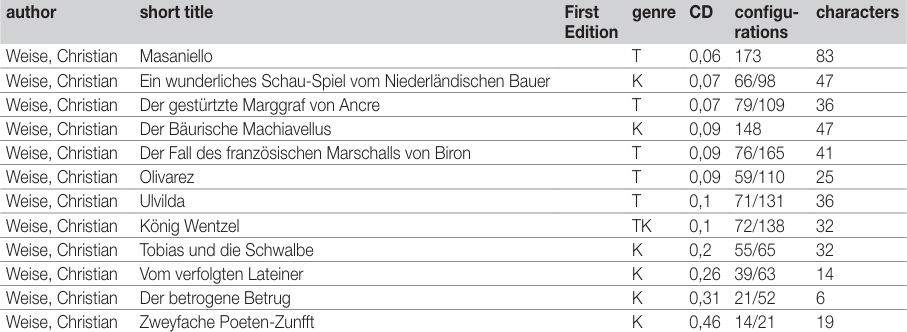

The dramatic texts by Christian Weise (1642–1708), premiered between 1670 and 1686 and first printed between 1681 and 1700 show a range of configuration density values from 0.06 to 0.1 for tragedies and from 0.07 to 0.46 for comedies (see table 3) [29]. Weise writes all his 60 plays as a schoolmaster in Zittau where he organizes a three day-performance with a biblical play, a historical play and a comedy every year [30]. As every pupil had to appear on stage and speak a few sentences, and as the plot was not to become too complicated or prolonged by several encounters of the characters, there are quite a few characters in every play appearing on stage only once, meeting only one or two others. These characteristics may explain their comparatively low configuration density. Although there is only one text bearing the term ‘domestic tragedy’ in its subtitle (Masaniello. Ein Trauerspiel) several other plays are categorized as tragedies. What they have in common is the fall or death of the protagonist in the main plot as well as the appearance of comic scenes doubling the message given in the serious parts in a more simple, entertaining way to make sure the pupils would catch the point [31]. What is striking at first sight is that here we can find two comedies in the domain of tragedy: Ein wunderliches Schau-Spiel vom Niederländischen Bauer und Der bäurische Machiavellus. The fact that both of them have 47 dramatis personae leads us to the general question if plays with high numbers of dramatis personae always show low configuration densities. Sorted by the number of characters the corpus divides into a group with a high number of dramatis personae (25 up to 47 characters), with configuration densities ≤ 0.1, and another group with less characters show ing values ≥ 0.2. It should be examined further if this hypothesis holds for all of Weise’s plays. For a large corpus of German plays, it might show that there is an absolute number of dramatis personae beyond which configuration densities tend to show low values just because of the many characters’ participation. Plays with a high number of characters but low configuration densities may be identified as starring groups of characters (choruses, talking groups, background actors).

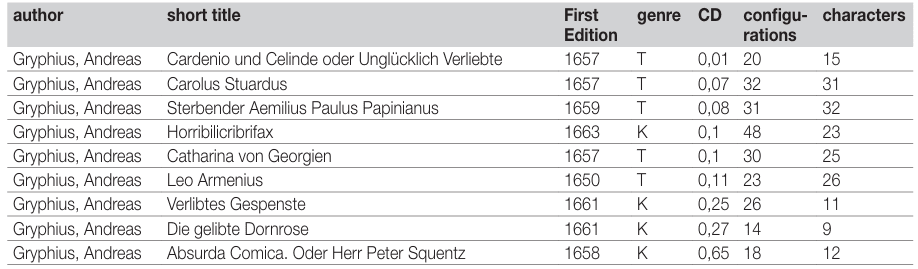

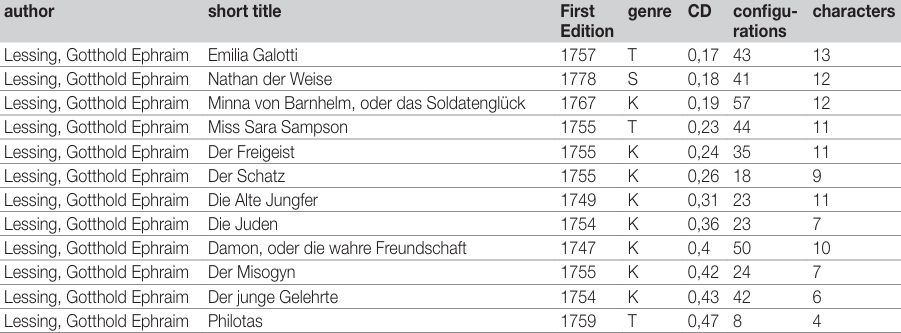

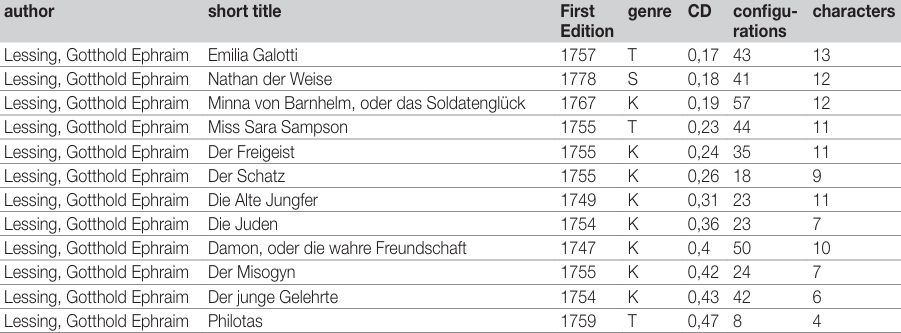

The plays by Gotthold Ephraim Lessing (1729 1781), premiered between 1747 and 1783 and first printed between 1747 and 1779 show a range of configuration density values between 0.17 and 0.47 for tragedies, and between 0.19 and 0.43 for comedies (see table 4). Here we can see a change in dramaturgical methods which manifests itself in a general rise of the configuration density. While plays by Gryphius start from configuration densities of 0.01, by Weise with 0.07, the lowest configuration density of a dramatic text of Lessing is 0.17. With the orientation on French classicism, promoted by Johann Christoph Gottsched and his followers from 1730 onwards the number of characters is reduced significantly. At the same time the episodic and repetitive structures of plots favoured by so called baroque writers, give way to single plots, carefully motivated [32]. These dramaturgical changes together with the emphasis on rationality during the Enlightenment, also produce plays concentrating on moral conflicts. This is the case for example, for the only outlier of a tragedy in the domain of comedies with a value of 0.47 [33]. In this play four characters are featuring in eight scenes. The main character is reflecting on his capture in two monologues and during six dialogic scenes. He is particularly scared by the idea to face his father as a loser but finally agrees to an exchange of prisoners. He takes the opportunity of the absence of interlocutors to commit suicide. The importance of discussions of moral aspects may also explain the relatively high configuration density of the tragic play Miss Sara Sampson. Looking at Lessing’s comedy with the lowest configuration density, Minna von Barnhelm, helps us to learn even more about the content structures corresponding to configuration density. Minna von Barnhelm is conceived when Lessing wants to turn away from the deriding comedy in the style of the Gottsched school. While Gottsched wants to righten the spectator by letting him reflect on a ridiculous protagonist [34], Lessing does not believe in the positive effects of negative examples [35]. In his opinion comedy is to teach the spectators to depict ridiculous and exaggerated behavior under all circum stances. This is why Major von Tellheim in Minna von Barnhelm is painted not only negative in his haughty behavior towards Minna but is also portrayed to be an exemplary character [36]. Some scenes with side characters only serve to illustrate repeatedly his kind-hearted ness. See for example the encounters with his servant Just, with his former subordinate Werner and widow Marloff, and, for the other protagonist, the one-time appearance of the gambler Riccaut de la Marliniere as an evidence that Minna’s passion for gambling not only yields the tantalizations of Tellheim but also charitable actions. Having fulfilled their function the side characters then do not enter the stage again. These aspects as well as the unique appearance of Minna’s uncle, serving as a deus ex machina, are responsible for the relatively low configuration density of that play.

A résumé of the results with regard to genre differ ences in the whole corpus (see table 1) looks as follows: comedies tend to show higher values than tragedies. In the entire corpus, comedies range from 0.07 to 0.65 while tragedies range from 0.01 to 0.47. Disregarding the outliers (Horribilicribrifax, Niederländischer Bauer, Bäurischer Machiavellus, Minna von Barnhelm, Miss Sara Sampson and Philotas) there is a tendency for plays figuring a configuration density ≥ 0.2 to be comedies whereas lower configuration densities are a hint for a plot with tragic conflicts and a bad ending. Moreover it is striking that there are more comedies with low values than tragedies with high values. The most important coefficients to lower the configuration densities of comedies considerably proved to be an unusual high number of dramatis personae as well as functional characters only starring in part of the plot. On the contrary, increasing the configuration densities for tragedies seems to be related to the rising importance of moral conflicts in the plot. The only example of that phenomenon is Lessing’s Philotas. As these results are only based on a small number of plays it seems desirable to test them on larger corpora, as for example all the dramatic texts from the 17th and 18th century available in the German Textgrid Corpus [37]. The outliers in configuration density then may prove as statistically irrelevant outliers but this question has to be postponed for later studies [38].

Apart from this deductive method of investigation there is a second approach of interpreting the data in this paper. As it seems likely that those plays with a high configuration density (the eight plays in the fourth quartile of the data, see table 1) have something in common they should be looked upon together in more detail in a last step. They are treated by author because this seems to be the most meaningful method. Lessing’s Die Juden is about the investigations into who has assaulted the baron in the beginning and who rescued him. Damon Oder die wahre Freundschaft deals with the fraud of Leander who does not tell his friend Damon that the ship of Leander has sunk with all his charge. Hiding this also from the widow who wants to marry either Damon or him depending on the size of their estate Leander quickly obliges his friend Damon to help each other in case the other would fall in financial trouble one day. The discussion about wealth, fidelity and reconciliation are conducted altogether. In Der Misogyn Hilaria crossdresses as Lelio to dissuade Wumshäter (Women’s hater), the father of her beloved Valer from his misogyny. In the end Wumshäter admits to accept a daughter in law if she would resemble Lelio to the point. In Der junge Gelehrte there is no difference in knowledge but the need to correct the ideas of certain characters be it the focus on property or fame or the fixation on marriage. The comedies of Lessing show a tendency to discuss moral topics and aspects of behavior in attendance of the respective characters. Whereas all of the aforementioned plays use differenc es in knowledge to amuse the spectator, Philotas is an example of a disguise in a tragedy ending seriously. The concealment of his thoughts offers the possibility for the protagonist to feign good will while actually pursuing and fulfilling the plan to commit suicide. To conclude, in the plays of Lessing the high presence of the characters on stage is about unveiling stereotypes by actions or discussing concepts like friend ship, gender, conscience, passion, rationality and justice. Besides that we can find non-moralistic topics and motives in the two comedies of Weise in the last quartile: in the case of Der betrogene Betrug, variating the theme of the golden pot of Plautus’ Aulularia, all the characters try to hide or find a hidden treasure and are therefore keeping secrets before each other. [39] The discrepant awareness of the characters on stage at the same time rises the fun of the spectator. In Die zweyffache Poetenzunft of the same author the high configuration density does not correspond to a specific action pattern. Here the members of two guilds are competing rhetorically in inventing their respective patron, their emblem, and their posts. The main point is their competition in making (bad) verses by trying to avoid loanwords in vain. Doing so they show up on the stage together for the most time of the play. [40] The only play by Andreas Gryphius in the last quartile Absurda Comica oder Herr Peter Squentz has already been treated above. As mentioned there the high configuration density is due to the subject: a performance of a play in front of an audience which stars most of the characters during all configurations.

Isolating plays with a high configuration density thus forms into three groups of plays: firstly, there is a group of plays where an observer is installed with in the fictional world. These plays are about hearing and seeing each other, competing (often on a theatre stage) or just fulfilling a task properly. Secondly, there are plays about objects to hide and to seek, identities to uncover in an action oriented manner. Thirdly, there are plays which are about serious concepts to be discussed from different angles by the major part of the characters. These findings are a hint that the inductive approach to plays with a similar configuration density leads to correlations of the average population density with topics and forms of literary history.

This paper started with thoughts on ‘distant’ vs. ‘close reading’ and ‘analysis’ vs. ‘reading’. The results may be related to these concepts as follows: the distant reading, i.e. the digitally assisted computation of the configuration densities had to be combined with close readings to make sense of the numbers. The results can in no way be simply read but demand a sound analysis whose main features where only to be sketched in this paper.

Table 1. Configuration densities of plays by Andreas Gryphius, Christian Weise and Gotthold Ephraim Lessing (outliers marked boldly).

Table 1. Configuration densities of plays by Andreas Gryphius, Christian Weise and Gotthold Ephraim Lessing (outliers marked boldly).

Table 2. Configuration densities of plays by Andreas Gryphius.

Table 3. Configuration densities in plays by Christian Weise.

Table 4. Configuration densities in plays by Gotthold Ephraim Lessing.

Note

Table 3. Configuration densities in plays by Christian Weise.

Table 4. Configuration densities in plays by Gotthold Ephraim Lessing.

Note

2 F. Moretti, Conjectures on World Literature, in «New Left Review» 1 (2000), pp. 54-68; Id., Distant Reading, London, Verso, 2013.

3 F. Moretti, Graphs, maps, trees. Abstract models for literary history, London [u.a.], Verso 2005. For a discussion of this book see for example J. Goodwin and J. Holbo (eds.), Reading Graphs, Maps, Trees. Critical responses to Franco Moretti, Anderson (South Carolina), Parlor Press 2011, http:// www.parlorpress.com/pdf/ReadingMapsGraphsTrees.pdf (08.12.2015).

4 S. Ramsay, Reading Machines: Toward an Algorithmic Criticism, Urbana (Ill)., Univ. of Illinois Press 2011. He tries to answer, for example, the question, if it is possible to under stand the characters of Virginia Woolf’s The Waves as different aspects of a mind with the help of lists of distinctive words for each character generated by algorithms.

5 M.L. Jockers, Macroanalysis. Digital Methods and Literary History, Urbana-Chicago-Springfield, University of Illinois Press 2013.

6 The following publications are focused on the connection of digital methods and literary history (novels, literary and scientific journals) as well: L. Tatlock and M. Erlin (eds.), Distant Readings. topologies of German culture in the long nineteenth century, Rochester, Camden House 2014; S. Allison, R. Heuser, M. Jockers, F. Moretti, M. Witmore, “Quantitative Formalism: An Experiment” Literary Lab Pamphlet 1 (2011) http://lit lab.stanford.edu/LiteraryLabPamphlet1.pdf (08.12.2015); R. Heuser, L. Le-Khac, “A Quantitative Literary History of 2,958 Nineteenth-Century British Novels: The Semantic Cohort Method”, Literary Lab Pamphlet 4 (2012) http://litlab.stan ford.edu/LiteraryLabPamphlet4.pdf (08.12.2015); M. Algee Hewitt, M. McGurl, «Between Canon and Corpus: Six Perspectives on 20th-Century Novels», Literary Lab Pamphlet 8 (2015), http://litlab.stanford.edu/LiteraryLabPamphlet8.pdf (08.12.2015).

7 Recently there have been efforts to gain an overview of rese arch projects in the field (see for example the Minutes of the Workshop Computer-based analysis of drama and its uses for literary criticism and historiography on http://comedy. hypotheses.org/12 (08.12.2015) and especially the research discussed in part I).

8 This goes back to a concept of Solomon Marcus (see part I of the paper).

9 I am very grateful to Manuel Burghardt, Thomas Crombez, Hartmut Ilsemann and Christof Schöch for discussing this paper with me.

10 S. Marcus, Mathematische Poetik, Frankfurt am M., Athenäum, 1973 [first published Bucuresti, Editura Academiei. 1970]).

13 Poetics and Mathematics. Special issue of the journal «POETICS», Mouton, The Hague, no. 10 (1974); The formal study of drama. POETICS 6, 3/4 (1977); The Formal Study of Drama, II. POETICS 13, 1/2 (1984).

14 The configuration matrix became better known through Manfred Pfister’s book The Theory and Analysis of Drama, first published in German in 1977 (M. Pfister, The Theory and Analysis of Drama, Cambridge u.a., Cambridge Univ. Press, 1993, p. 239).

15 H. Ilsemann, Shakespeare disassembled. Eine quantitative Analyse der Dramen Shakespeares, Frankfurt am M., Peter Lang 1998.

16 H. Ilsemann, Shakespeare disassembled, cit., pp. 266-275. The tool he developed unfortunately does not read xml but demands a proprietary markup: http://dramenanalyse.de/da/jsp/ (08.12.2015).

17 See P. Swanborn, Case Study Research. What, Why and How? (Los Angeles, SAGE, 2010), 2. To be precisely, this is a ‘multiple case study’ because each of the 32 plays counts as a case.

18 See R.J. Alexander, Das deutsche Barockdrama, Stuttgart, Metzler 1984; P.-A. Alt, Tragödie der Aufklärung. Eine Einführung, Tübingen and Basel, Francke 1994; E. Catholy, Das deutsche Lustspiel. Vom Mittelalter bis zum Ende der Barockzeit, Stuttgart, Kohlhammer 1969; E. Catholy, Das deutsche Lustspiel. Von der Aufklärung bis zur Romantik, Stuttgart, Kohlhammer 1982; G.-M. Schulz, Einführung in die deutsche Komödie, Darmstadt, WBG 2007.

19 See for work on genre characteristics with other digital methods: C. Schöch, «Corneille, Molière et les autres. Stilometrische Analysen zu Autorschaft und Gattungszugehörigkeit im französischen Theater der Klassik», in C. Schöch and L. Schneider (eds.), Literaturwissenschaft im digitalen Medienwandel Mainz, Berlin 2014, pp. 130-57. http://web.fuberlin.de/phin/beiheft7/b7i.htm (8.12.2015). Whereas these papers rely on algorithms clustering texts with regard to their most frequent words (MFW) Michael Witmore and Johnathan Hope used the tool Docuscope to tag a corpus with 200 millions of English words with a grammatically, semantically and rhetorical category system consisting of 101 functional linguistic categories called «Languages Action Types» (LAT). For Docuscope, see D. Kaufer, S. Ishizaki, B. Butler, J. Collins, The Power of Words: Unveiling the Speaker and Writer’s Hidden Craft, New Jersey-London, Lawrence Erlbaum Associates 2004, for results of the LAT-Analysis of Shakespeare’s play, see, for example, M. Witmore and J. Hope, «Shakespeare by the Numbers: On the Linguistic Texture of the Late Plays», in S. Mukherij and R. Lyne (eds.), Early Modern Tragicomedy, London, Boydell and Brewer 2007, pp. 133-53.

20 Fotis Jannidis coined the term ‚Kontrollpeilung‘ (monitoring position fixing) for the possibility of complementing, supporting and correcting findings of traditional philological research with the help of digital methods (see F. Jannidis, «Methoden der computergestützten Textanalyse» in Methoden der literatur- und kulturwissenschaftlichen Textanalyse, ed. Vera Nün ning, Stuttgart, Metzler 2010, pp. 109-32, here p. 118.

21 See for instance the multidimensional concept of genre in: D. Biber and S. Conrad (eds.), Register, Genre and Style, Cambridge, Cambridge University Press 2011.

22 Andreas Gryphius comedy Verlibtes Gespenst. Gesang Spiel/Diegelibte Dornrose. Schwertz-Spill is computed as it were two plays. It is actually a twofold play with separated plots where I,1 of the first play is followed by I,1 of the second one and so forth.

23 An exception is his tragedy Leo Armenius which is subdivided into scenes, which follow the idea of configurations.

24 Experiments with Machine Learning-Algorithms trained to identify character movements plotting the stage instructions proved to be highly complicated and still need intensive work (see K. Dennerlein, «Automatic recognition of structu ral aspects of a play – The scenic presence of characters computed with the help of machine learning», in History of Comedy. (Digitally assisted) History of German comedy in the Old Empire in 17th and 18th century (December 2015) http:// comedy.hypotheses.org/.

25 Textgrid Collection (https://textgridrep.de [08.12.2015]).

27 See N. Kaminski, Der Liebe eisen-harte Noth. ‘Cardenio and Celinde’ im Kontext von Gryphius’ Märtyrerdramen, Tübin gen, Niemeyer 1992, pp. 153–162.

28 It may be discussed if it is right to term this play a tragedy. Gryphius himself states in the preface that the characters are almost too little in status for a tragedy, that the rhetorical style is too low and that it is not about a state affair (see A. Gryphius, Gesamtausgabe der deutschsprachigen Werke, ed. Marian Szyrocki und Hugh Powell, Tübingen, Niemeyer 1965, vol. 5 Trauerspiele II. ed. Hugh Powell, p. 148.).

29 The selection of plays from the large œuvre of Weise follows the frequency of references in existing research on his plays.

30 C. Weise, Sämtliche Werke, ed. John D. Lindberg, Berlin New York, de Gruyter 1971 ff., vol. 11, p. 166; K. Zeller, Pädagogik und Drama. Untersuchungen zur Schulcomödie Christian Weises, Tübingen, Niemeyer 1980.

31 While Peter-André Alt takes the existence of the comic scenes as a counter-argument for classifying these dramatic texts as tragedies it seems to make more sense to accept that there were almost no dramatic texts without comical elements atthat time (see P.-A. Alt, Tragödie der Aufklärung, cit., p. 48). The configuration density of the one play explicitly identified as tragicomedy does not mark it to be exceptionally different from the tragedies either (the subtitle contains the expression “Eine Misculance, von der alsogenannten Tragoedie und Comoedie”).

33 See the chapter «Aufklärung durch moralische Analyse. Les sings Philotas» in W. Ranke, Theatermoral: moralische Argumentation und dramatische Kommunikation in der Tragödie der Aufklärung, Würzburg, Königshausen & Neumann 2009, pp. 396-470.

34 J.C. Gottsched, Versuch einer Critischen Dichtkunst (Unveränd. photomech. Nachdruck der 4. ver. Aufl. Leipzig 1751, Darmstadt, WBG 1962) [First Edition Leipzig 1730]), p. 643.

35 G.E. Lessing, «Hamburgische Dramaturgie», in G.E. Lessing, Werke, Bd. IV Dramaturgische Schriften, München, Hanser 1973, pp. 230-720, here p. 363; for the interrelation of the ory and dramatic structures see also A. Kornbacher-Meyer, Komödientheorie und Komödienschaffen Gotthold Ephraim Lessings, Berlin, Duncker & Humblot 2013, pp. 268-302.

37 For this corpus see footnote 25.

38 See the paper T. Crombez, K. Dennerlein, Configuration Density and Genre in Early Modern Drama (French, English, German, Dutch). [work in progress]

39 Vgl. D. Fulda, Schau-Spiele des Geldes. Die Komödie und die Entstehung der Marktgesellschaft von Shakespeare bis Lessing, Tübingen, Niemeyer 2005, pp. 303-26.

40 In Vom verfolgten Lateiner by Christian Weise we have a combination of the action-based and the discursive variant by the way: most of the time members of the court and their families discuss about future spouses. Then, in the fourth act students dress two chimney sweepers as noblemen, to later qualify as spouses for the daughters in unmasking the pretended betrayal.

¬ top of page