« indietro

Computational methods of literary criticism: an example of use in Marco Polo’s Devisement du monde

di Dominique Lapierre,

Dominique.lapierre@iut-tlse3.fr

Jamie Tehrani

Abstract:

Textometry has developed powerful techniques for analysing large bodies of text using distant reading. For their part, many scholars in Literature stick to close reading. Inspired by the work of Anthropologist Jamie Tehrani on a famous fairy tale a new approach was taken using phylogenetics which reconciles close and distant reading. This method was applied to four episodes of Marco Polo’s Devisement du monde. Using software originally dedicated to genetics, it was possible to outline a cartography of the narrative structures and to underline their parenthood.

Few authors from the Middle Ages have left as much legacy as Marco Polo: of his account in Kublay Khan’s Mongol Empire, one hundred and forty three manuscripts (MSS) have survived from seven centuries of copying and re-writing. About twenty six versions, written in thirteen languages, some translated in Latin – which was rather uncommon – before being re-translated in vernacular languages: a real nightmare for any searcher who intends to tackle a classification founded on a lost original manuscript. In his time, Luigi Foscolo Benedetto did it successfully, and his «Integrale Edizione» of Marco Polo’s texts remains an authority today [1]. However, uncertainties about the material used for each version are still numerous, for most of the classification was based on the incipit of the MSS. Following the works of Consuelo Wager Dutschke and Christine Gradat on the reception of Marco Polo’s texts [2], and Damon Mayaffre on logometry [3], this article stands at the crossroads of multiple branches of humanities such as History, Medieval literature and Ethnography. The focus is the religious and cultural diversity pervading a text which, according to the language it was copied into, bore the names – among others – of The Book of Marvels, The Description of the World or Il Milione. For the purpose of this study, fourteen versions of The Devisement du Monde were selected. Written in Old French, Venetian, Tuscan, Italian, Latin and English, they contrast in their content according to the audience they were addressed to. Inspired by the work of anthropologist Jamie Tehrani on a famous fairy tale [4], and in collaboration with him, a new approach was taken using phylogenetics. Originally directed to the study of parenthood among species, phylogenetics has been put into the service of humanities and found a favourable outcome. In a preceding study, phylogenetics had been tested on one episode – the Miracle of the Mountain – and showed results matching the current classification of Marco Polo’s text tradition. For this diachronic study of the text, four episodes dealing with miracles were selected. In extending this method to other episodes, the aim was to challenge the previous results with a larger panel and to demonstrate the use of phylogenetics applied to Marco Polo.

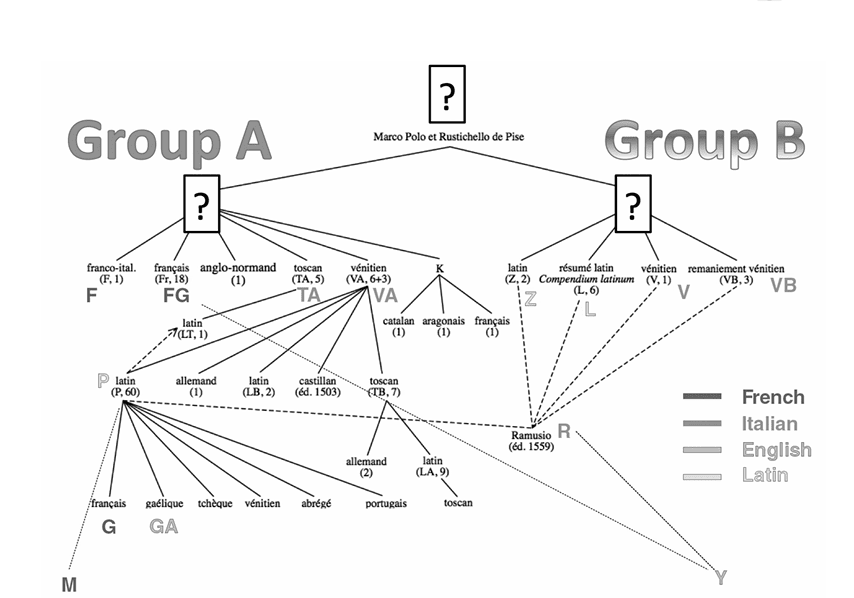

The tradition of Marco Polo’s texts can be divided into two main groups – A and B. The original manuscript. dictated by Marco Polo to Rustichello da Pisa is lost, and moreover so are the two subarchetypes from which these two groups derive. However, the selected corpus represents the major versions of both A and B (see graph 1). Before any interpretation, a short presentation of each version composing this corpus is necessary to fully understand the implications of the final results.

Graph. 1. Marco Polo text tradition, adapted from Christine Gadrat’s sketch.

Sources

Sources

Group A (French, Tuscan, Venetian, Latin and Gaelic)

The French versions don’t derive from a unique archetype and are not related together directly. However, they have much in common and are relatively close to the original manuscript. which was written in French. F – also called Franco-Italian – is the most famous version of group A and for many scholars the favourite candidate for being the closest version to the lost original [5]. This assumption is based on the fact that it is written in French and that it is one of the most complete. How ever, it is not exempt of mistakes and italicized words, and other versions like French (FG), Tuscan (TA), and Venetian (VA) propose a better lection. Besides, it is sometimes less complete than Latin (Z), which is classified in group B. FG – also labelled Fr – shares the same ancestor as F but was re-written in ‘proper French’ and cleared from italicized words. Well-known for their rich illustrations, the MSS. of this version largely circulated within the French and English aristocracy from early 14th C. Among the thirteen surviving MSS., the latest critical edition of this version was chosen here [6].

Italian versions are composed of a Tuscan – TA – and a Venetian version – VA. TA counts five surviving copies. The manuscript elected for this work is TA2 [7], which despite some missing parts at the beginning and at the end, seems to be more conservative. It can be dated from the first part of the 14th C. This version is characterized by many omissions and abridgements, among which historical chapters about the Mongols. Some words are simply “tuscanized” without being re ally translated, as if the copyist didn’t understand the original text. VA – also called Milione – has produced an important number of translations in Latin, Tuscan, Spanish and German. The MS. we opted for is VA3 [8] and was copied in mid 15th C. Like in TA the text was reduced and some historical chapters are missing and others abridged. Comparing the remaining copies of VA to their translated works is a difficult task because the latter were based on MSS. closer to the original manuscript than the surviving VA copies.

The following versions derive from the versions here above. P– Translated into Latin from a Venetian copy, P was written in the first part of the 14th C. and then circulated quickly throughout Europe beyond the 15th C. Its success was accompained by many translations plus abridged versions [9]. P is noticeable for the changes made by its author – a Dominican priest named Francesco Pipino – who rearranged Marco Polo’s account into three books [10] and added depreciative comments on Eastern religions and towards muslims. It is probable that P used VA as a basis for his MS., though this assumption has been contested [11]. GA – Composed of a unique manuscript, this Gaelic version dates back to the 15th C. Written in Ireland, it contains other historical pieces in Gaelic and religious works [12]. The author who is unknown, largely adapted and made noticeable changes to the content of the Devisement du Monde. This work is divided into three books – like in P – and some parts seem to be directly borrowed from Hay ton’s Fleur de l’Orient. G – stands for the first edition in French, due to Estienne Groulleau in 1556 [13], and is based on a Latin version of the Devisement du Monde published in 1532 [14]. M – The last French edition which serves this study dates back to the 19th C. and was written by Eugène Müller [15]. Like in the three above versions – GA, G and P – Müller adopted the division of Marco Polo’s work into three books.

Group B (Latin, Venetian)

Group B (Latin, Venetian)

This group is composed of two Latin versions – Z and L – and of two Venetian versions – V and VB. The versions of this group are similar in the way that they are shorter versions of the text, but also present ad ditional material.

Z – L. Benedetto considered Z [16] as closer to the original manuscript than F, for it contains information that is found in no other version. Z dates back to the mid 15th C. but was discovered in Toledo at the beginning of the 20th C. L – This version seems to be more a shortened version of Z than a summary of the latter. One particularity of this version is that the copies made in Italy display chapter headings whereas the copies originating from Northern Europe have none [17]. V – Copied in late 15th C., V was probably made from a transcript of L or Z. Actually, there are spelling mis takes related to misunderstandings of the Latin translation [18]. There is only one extant manuscript [19]. Its content is reduced and sometimes elements which are developed in several chapters in the other versions are compacted here into one chapter. This version shares common points with Z but some elements are not found either in Z nor in F. What makes it more troubling is that there is no mention of this version from any known manuscript of the Middle Ages [20]. VB – Out of the three surviving MSS., two of the VB MSS. were copied in the second part of the 15th C. One belonged to Ramusio’s son and might have previously belonged to his father. This version is a re-writing of the Devisement and parts are omitted, inverted, cut or added and bear no chapter headings [21]. The narrator Marco Polo appears more frequently – Io Marco Polo – and Rustichello is not mentioned in the prologue [22]. In this manuscript one finds more dialogues and monologues than in any other version. Historical chapters have been omitted or suppressed, but geographical details have remained.

Compilations & translations (Italian, English)

Compilations & translations (Italian, English)

R – Giambatista Ramusio published the first edition of the Devisement in 1559 [23]. In the introduction of his second volume named Navigazioni e viaggi, Ramusio indicates that he used several MSS. to achieve his work, including a Latin version. Y – The last version used in this study was compiled by Sir Henry Yule [24] in the 19th C. and was based on FG and R. Yule’s English translation, whose sources were well known. It was used here to check the results of the phylogenetic approach.

Method

Method

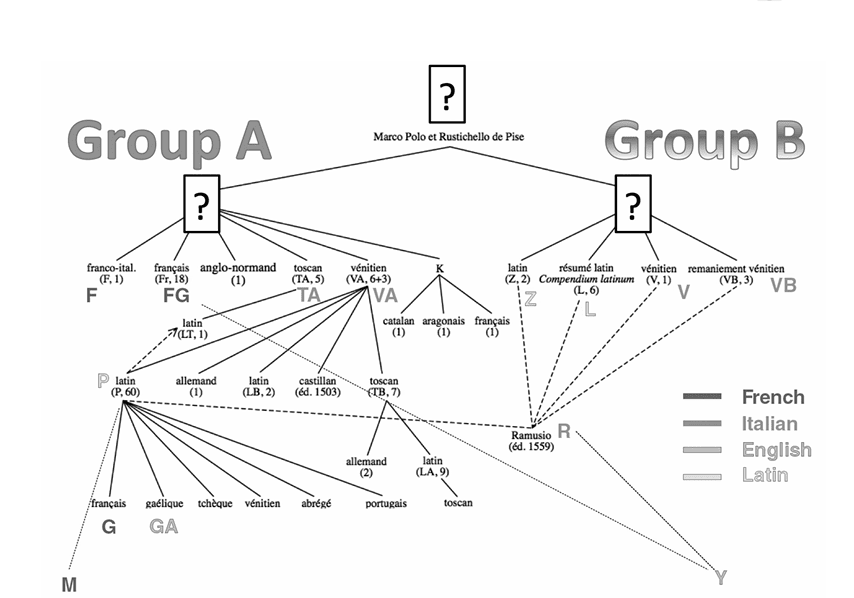

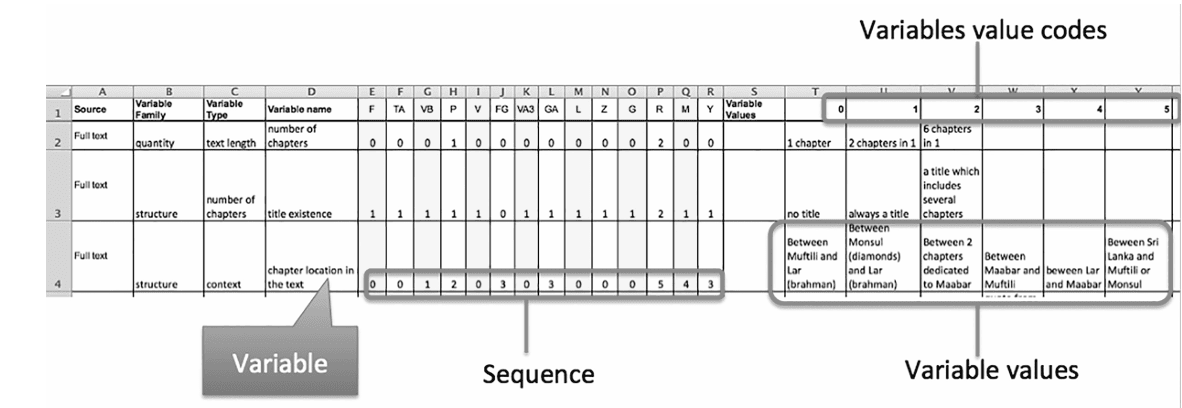

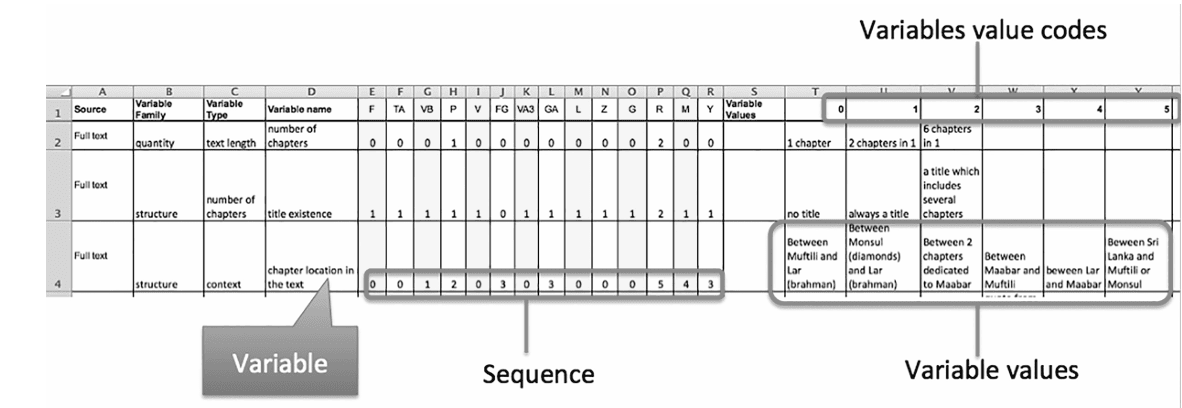

The modus operandi consists of both close reading and data processing. First, a number of variables are selected so that all the versions can be analysed in the same way. They are of two kinds: on the one hand syntactic variables and on the other hand semantic variables. The syntactic category includes formal aspects, such as the location of the episode in The Devisement, the number of chapters dedicated to it, the existence of chapter headings, and the number of words dedicated to the story. In the semantic category, one can find an swers to the basic Wh’s and How’s questions. Who? What? When? Where? How? Why? The set of versions will be aligned and each variable – ‘trait’ or ‘character’ in phylogenetics – will be entered in a nexus file (matrix like) and coded (see graph 2). According to the episode, between 37 and 51 of these variables were used [25]. Aligning the texts is equivalent to aligning biological sequence data. Each sequence of variable values will then be processed with software generating graphs which are then be interpreted.

Graph. 2. Matrix with encoded variations of the text

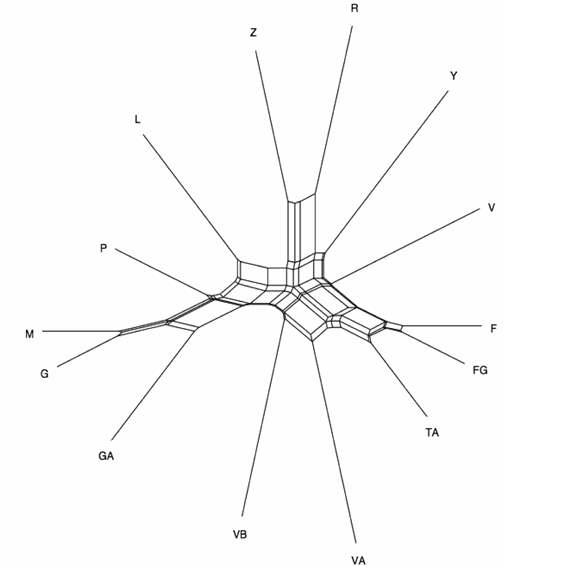

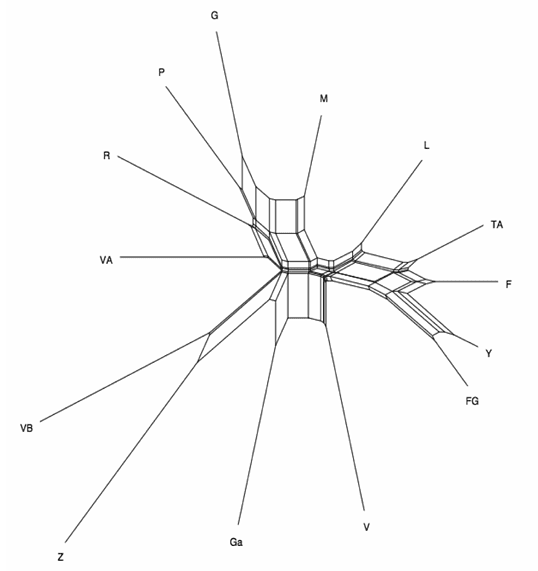

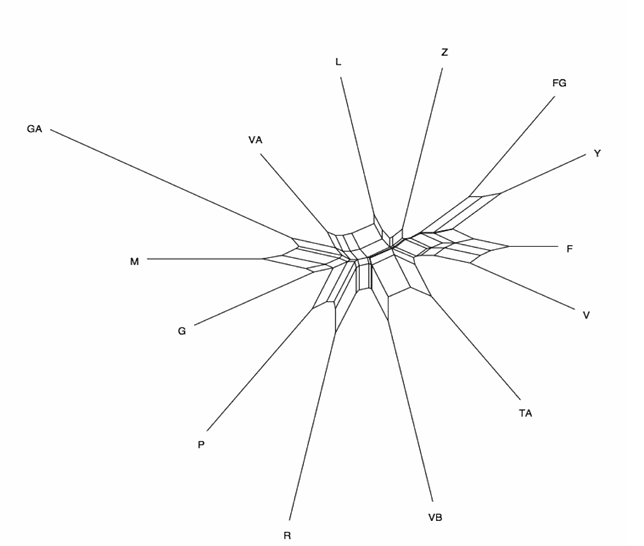

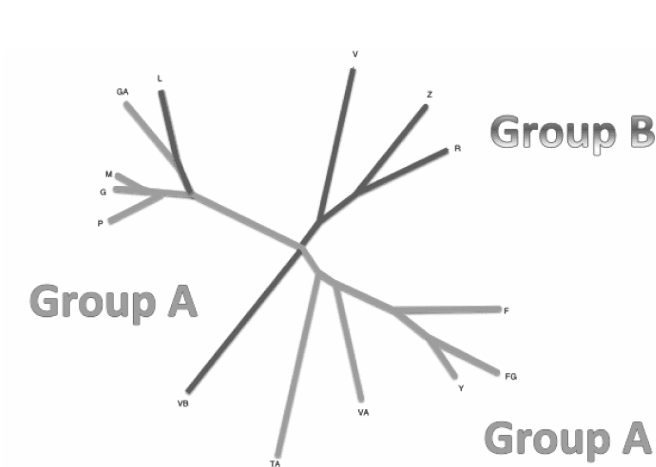

For the purpose of this study, several methods em ployed in phylogenetics were solicited. The first one consists of calculating the average number of mutations (changes of variables) required to get from one version of the tale to another using the software SplitsTree4 [26]. This method is distinct from genealogy as it is not meant to reconstruct an evolutionary history but rather to represent the conflicting signals in the data-set. These conflicting signals due to “contamination” – or mix of ver sions deriving from several ancestors – will be revealed in NeighborNet [27] graphs. NeighborNet is able to represent multiple conflicting relationships, which appear as «boxes» in the network. In case of several potential ancestors for a manuscript, the structure will show a specific web-like pattern [28]. On the contrary, whenever the graph will show a tree-like shape, the chances that the MSS. derive from a common ancestor will be higher.

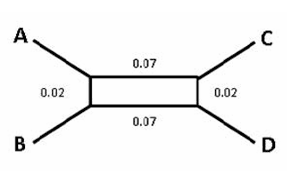

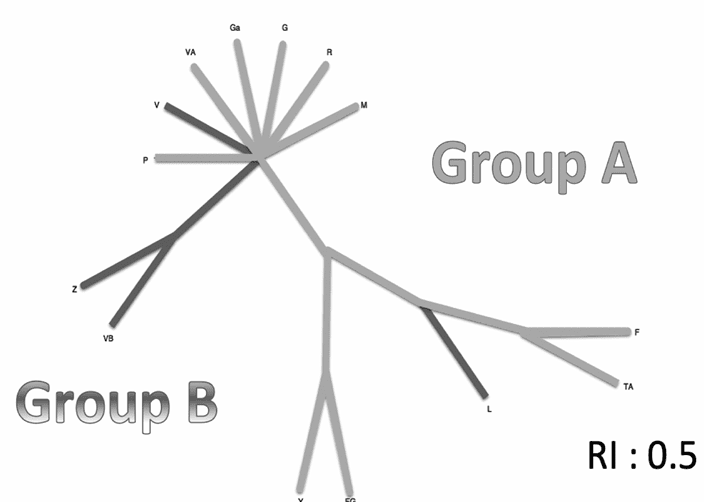

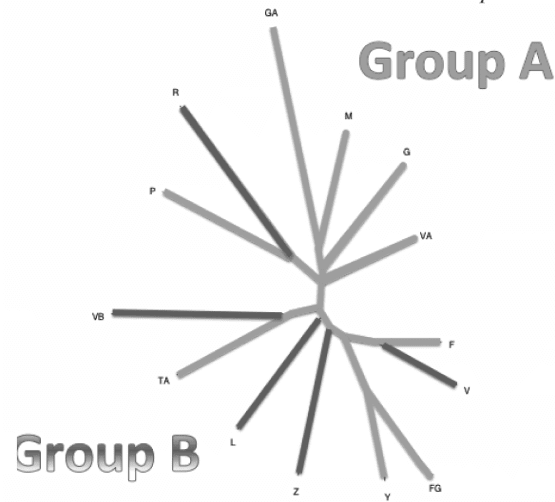

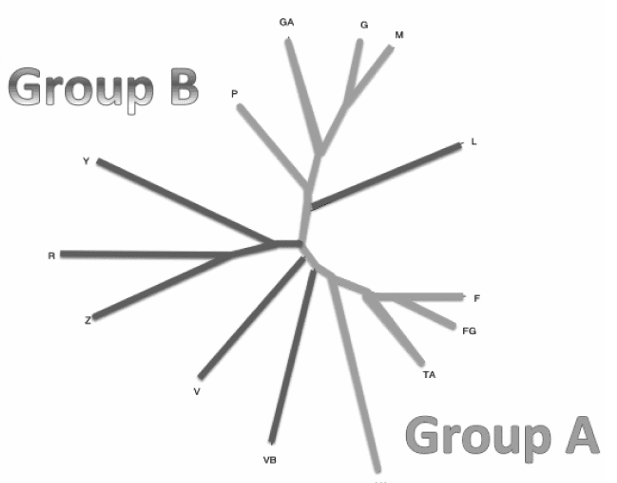

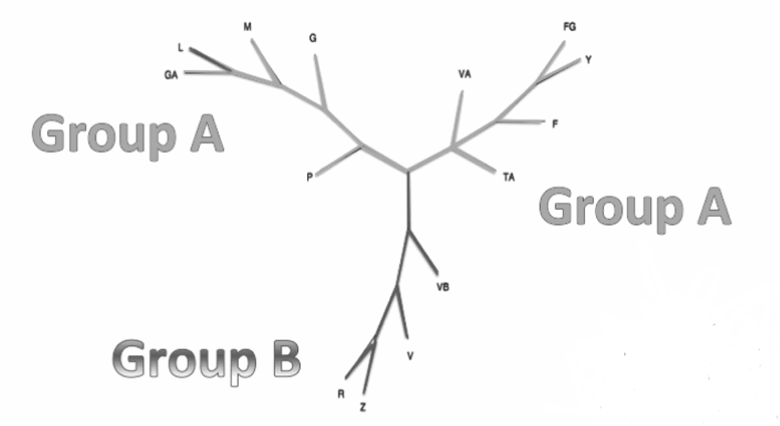

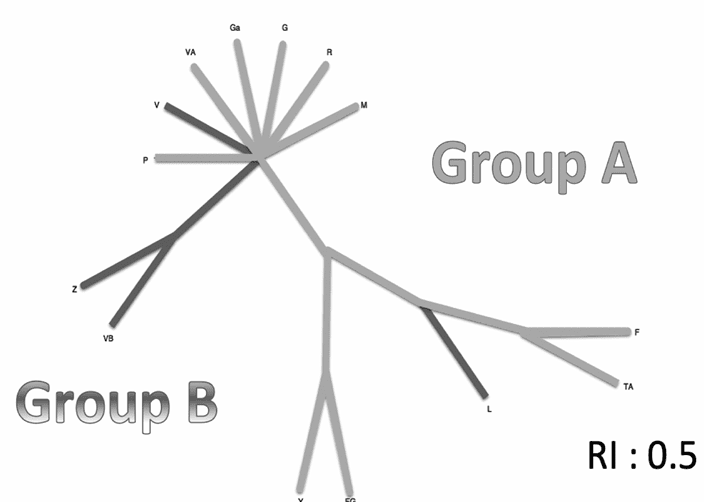

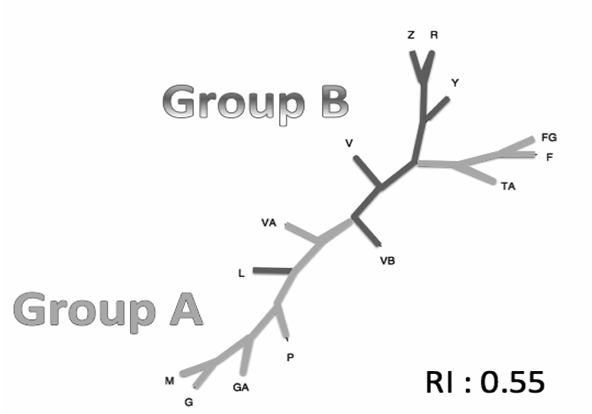

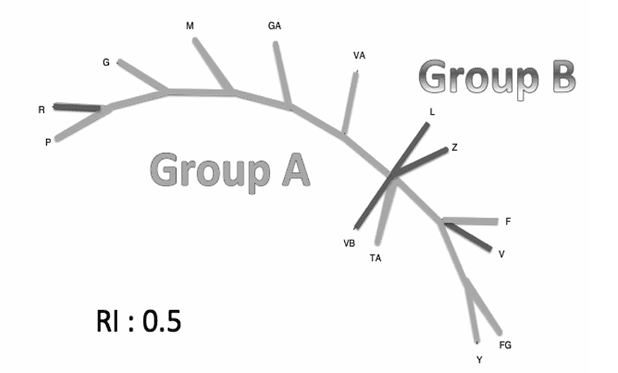

So in this example, A is closely related to B – the distance (i.e. number of mutations) that separates them is small (on average every trait would have to change 0.2 times to get from A to B). However, A is also somewhat similar to C (e.g. because of contamination), although they are separated by a larger distance than A and B (with each trait having to change 0.7 times). Instead of ignoring this information, NeighborNet shows the relationship between A and C as well as between A and B. The length of the branches is proportional to the distance separating them, so you can also see that A is much closer to B than to C. However, the number of mutations is not necessarily the same thing as chronological distance – sometimes a large number of mutations can occur very quickly – what biologists call «punctuated evolution». For example, a scribe may decide to make a lot of changes, or makes a lot of mistakes, etc. If contamination can increase distances, in some cases it may reduce them (e.g. copies that include content from old manuscripts may cut distances to the root). This is the case for the Yule version which was written in the 19th C. and appears close to FG, written in the 14th Century (see graph 3). Neighbor-Joining trees are simplified NeighborNets. Our attention will be focused on the cross -connections of group A and group B interpreted as a contamination of versions belonging to two different groups. As stated by David Morrisson, cross-connections between branches might represent horizontal flow (hybridization, lateral transfer), in addition to the vertical flow (from parent to offspring) repre sented by the tree branches [29] (see graphs 7 to 10). An other method used consisted in creating Parsimony Trees generated by PAUP4 [30]. This method minimises the number of copying errors/innovations required to explain the relationships among the texts. The shorter the branches, the closer the versions. The fit between the data and the tree was assessed using the Reten tion Index (RI) ranking from 1 to 0. The closer to 1, the more probable that the versions derived from one source. Inversely, a Retention Index ranking toward 0 indicates different sources (see graphs 11 to 14).

So in this example, A is closely related to B – the distance (i.e. number of mutations) that separates them is small (on average every trait would have to change 0.2 times to get from A to B). However, A is also somewhat similar to C (e.g. because of contamination), although they are separated by a larger distance than A and B (with each trait having to change 0.7 times). Instead of ignoring this information, NeighborNet shows the relationship between A and C as well as between A and B. The length of the branches is proportional to the distance separating them, so you can also see that A is much closer to B than to C. However, the number of mutations is not necessarily the same thing as chronological distance – sometimes a large number of mutations can occur very quickly – what biologists call «punctuated evolution». For example, a scribe may decide to make a lot of changes, or makes a lot of mistakes, etc. If contamination can increase distances, in some cases it may reduce them (e.g. copies that include content from old manuscripts may cut distances to the root). This is the case for the Yule version which was written in the 19th C. and appears close to FG, written in the 14th Century (see graph 3). Neighbor-Joining trees are simplified NeighborNets. Our attention will be focused on the cross -connections of group A and group B interpreted as a contamination of versions belonging to two different groups. As stated by David Morrisson, cross-connections between branches might represent horizontal flow (hybridization, lateral transfer), in addition to the vertical flow (from parent to offspring) repre sented by the tree branches [29] (see graphs 7 to 10). An other method used consisted in creating Parsimony Trees generated by PAUP4 [30]. This method minimises the number of copying errors/innovations required to explain the relationships among the texts. The shorter the branches, the closer the versions. The fit between the data and the tree was assessed using the Reten tion Index (RI) ranking from 1 to 0. The closer to 1, the more probable that the versions derived from one source. Inversely, a Retention Index ranking toward 0 indicates different sources (see graphs 11 to 14).

NeighborNet Trees generated by SplitTree4 software

So in this example, A is closely related to B – the distance (i.e. number of mutations) that separates them is small (on average every trait would have to change 0.2 times to get from A to B). However, A is also somewhat similar to C (e.g. because of contamination), although they are separated by a larger distance than A and B (with each trait having to change 0.7 times). Instead of ignoring this information, NeighborNet shows the relationship between A and C as well as between A and B. The length of the branches is proportional to the distance separating them, so you can also see that A is much closer to B than to C. However, the number of mutations is not necessarily the same thing as chronological distance – sometimes a large number of mutations can occur very quickly – what biologists call «punctuated evolution». For example, a scribe may decide to make a lot of changes, or makes a lot of mistakes, etc. If contamination can increase distances, in some cases it may reduce them (e.g. copies that include content from old manuscripts may cut distances to the root). This is the case for the Yule version which was written in the 19th C. and appears close to FG, written in the 14th Century (see graph 3). Neighbor-Joining trees are simplified NeighborNets. Our attention will be focused on the cross -connections of group A and group B interpreted as a contamination of versions belonging to two different groups. As stated by David Morrisson, cross-connections between branches might represent horizontal flow (hybridization, lateral transfer), in addition to the vertical flow (from parent to offspring) repre sented by the tree branches [29] (see graphs 7 to 10). An other method used consisted in creating Parsimony Trees generated by PAUP4 [30]. This method minimises the number of copying errors/innovations required to explain the relationships among the texts. The shorter the branches, the closer the versions. The fit between the data and the tree was assessed using the Reten tion Index (RI) ranking from 1 to 0. The closer to 1, the more probable that the versions derived from one source. Inversely, a Retention Index ranking toward 0 indicates different sources (see graphs 11 to 14).

So in this example, A is closely related to B – the distance (i.e. number of mutations) that separates them is small (on average every trait would have to change 0.2 times to get from A to B). However, A is also somewhat similar to C (e.g. because of contamination), although they are separated by a larger distance than A and B (with each trait having to change 0.7 times). Instead of ignoring this information, NeighborNet shows the relationship between A and C as well as between A and B. The length of the branches is proportional to the distance separating them, so you can also see that A is much closer to B than to C. However, the number of mutations is not necessarily the same thing as chronological distance – sometimes a large number of mutations can occur very quickly – what biologists call «punctuated evolution». For example, a scribe may decide to make a lot of changes, or makes a lot of mistakes, etc. If contamination can increase distances, in some cases it may reduce them (e.g. copies that include content from old manuscripts may cut distances to the root). This is the case for the Yule version which was written in the 19th C. and appears close to FG, written in the 14th Century (see graph 3). Neighbor-Joining trees are simplified NeighborNets. Our attention will be focused on the cross -connections of group A and group B interpreted as a contamination of versions belonging to two different groups. As stated by David Morrisson, cross-connections between branches might represent horizontal flow (hybridization, lateral transfer), in addition to the vertical flow (from parent to offspring) repre sented by the tree branches [29] (see graphs 7 to 10). An other method used consisted in creating Parsimony Trees generated by PAUP4 [30]. This method minimises the number of copying errors/innovations required to explain the relationships among the texts. The shorter the branches, the closer the versions. The fit between the data and the tree was assessed using the Reten tion Index (RI) ranking from 1 to 0. The closer to 1, the more probable that the versions derived from one source. Inversely, a Retention Index ranking toward 0 indicates different sources (see graphs 11 to 14).NeighborNet Trees generated by SplitTree4 software

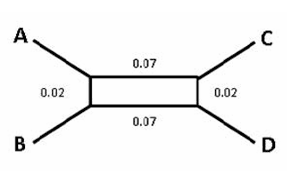

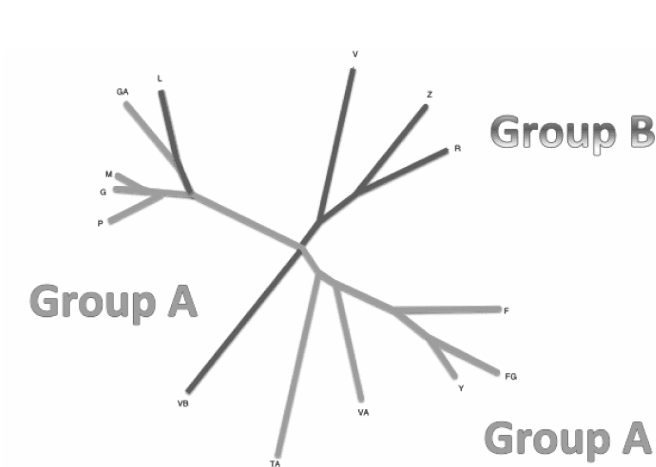

Graph 3: The miracle of the mountain

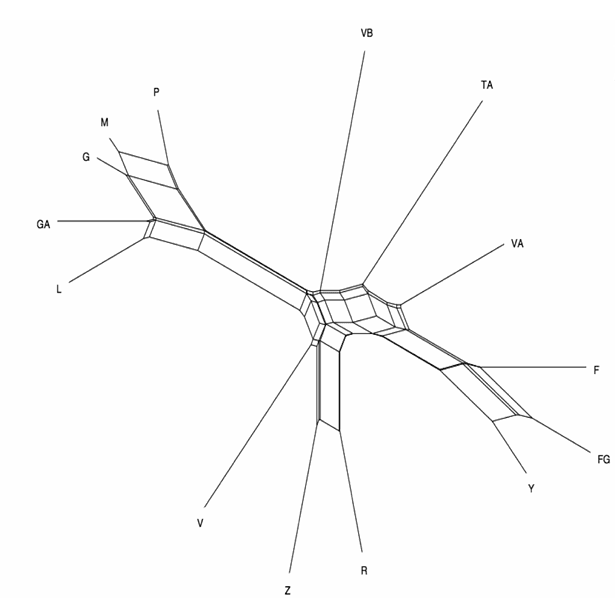

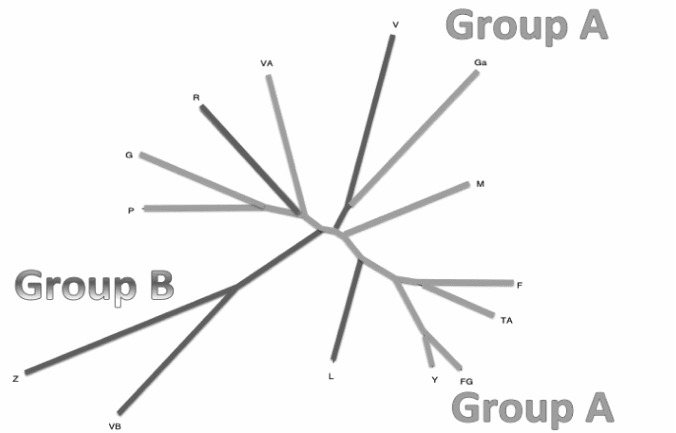

Graph 6: The miracle of St Thomas

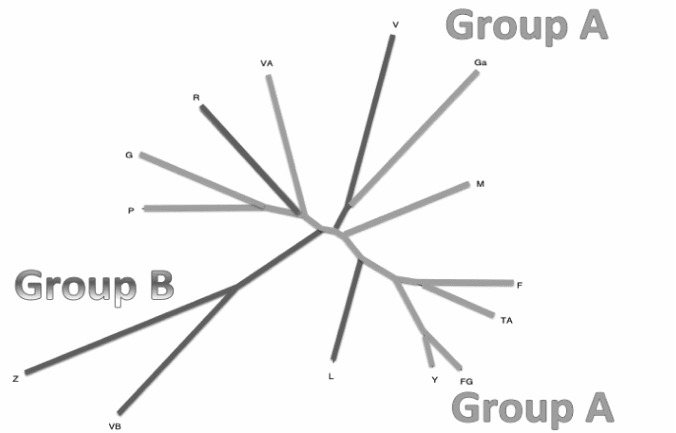

Neighbor-Joining Trees generated by SplitTree4 software

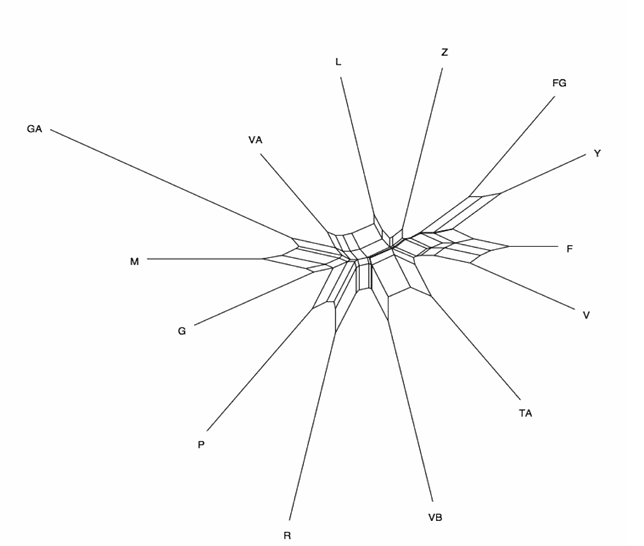

Graph 7: The miracle of the mountain

Graph 4: The Miracle of St Leonard |

Graph 5: The miracle of the column |

Graph 6: The miracle of St Thomas

Neighbor-Joining Trees generated by SplitTree4 software

Graph 7: The miracle of the mountain

Graph 8: The miracle of the column

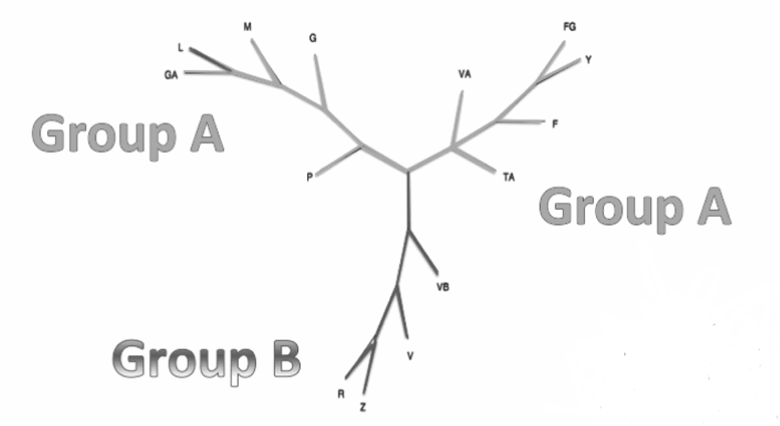

Parsimony Trees generated by PAU4

Graph 11: The miracle of the mountain

Graph 12: The miracle of the column

Graph 9: The miracle of St Thomas |

Graph 10: The miracle of St Leonard |

Parsimony Trees generated by PAU4

Graph 11: The miracle of the mountain

Graph 12: The miracle of the column

Graph 13: The miracle of St Leonard |

Graph 14: The miracle of St Thomas |

Before going into the details, the most striking thing about these graphs – wether generated by SplitsTree4 or PAUP4 – is their lack of consistency. In fact, according to the episodes, these representations differ from each other. Had the episodes taken from The Divisement du Monde followed the same pattern and used the same sources, the graphs would have looked similar. On the contrary, they are totally unlike. Let’s focus on the episodes one by one and see what we can learn from these trees.

The tales

The tales

They all deal with miracles, which happen to be less important in number than wonders in the Devisement du Monde. If wonders are related to natural or man-made phenomenons, miracles are due to God’s sign. Three of them appear during the ongoing journey of Marco Polo to China – St Leonard, the Mountain, the Column – and one during the returning journey to Venice – St Thomas. Interestingly, although some episodes are common to all the versions, their content differs in many ways. Besides, the amount of words for each episode varies greatly depending on the version. How can these disparities be interpreted?

Saint Leonard

Saint Leonard

The miracle of the convent Saint Leonard is the first to be mentioned in the narrative. It is located in Georgia, and comes after a description of the Iron Gate, supposedly dating back to Alexander the Great. Once a year, between the first day of Lent and Easter Eve, fishes of all kind appear and then disappear for the rest of the year. In their titles, most of the versions attract the reader with the mention of the king of the region. VA is the only version which, in its title, advertises the miracle as the main topic of the chapter. It is also the only version which offers a whole chapter dedicated to the tale, which shows a particular interest for it. Conversely, in Miller’s version, the miracle has turned into something worth noticing, but not more. The miracle has fallen to the funny story, a simple anecdote. The use of «they» in «they say something noteworthy about their land...» shows the distance the narrator takes from the story, which sounds like «hear say» more than a true fact. Four centuries separate the two versions and maybe a better knowledge of natural life. The Retention Index (0.55) of the Parsimony Tree is slightly higher than other episodes like The column or St Thomas. The episode appears as being moderately contaminated by other versions (see graph 14). However, the general pattern of the NeighborNet is more web-like than tree-like. The large boxes indicate con f licting signals which are not distributed evenly. This suggests that the episode has had more than one an cestor, which explain the variations between the ver sions (see graph 4). The Neighbor-joining Tree shows that R borrowed from Z and so did Yule who included parts of Ramusio’s text in his version (see graph 10).

The Miracle of the Mountain

The Miracle of the Mountain

In Iraq this time, after telling how the caliph of Bagdad was made to starve by the Mongols, the narrator switches to another caliph, who wants to clear out a Christian community living on his lands. To do so, he uses a passage taken from the Gospels to challenge the Christians. They are required to move a mountain by the power of their faith; if they fail, they will have to convert to Islam or die. The Christians are saved by a one-eyed cobbler whose prayer makes the mountain move. Ironically, some Saracens convert and so does the caliph. In the NeighborNet Tree (see graph 3) the elongated boxes make the network look more like a tree, which indicates a vertical pattern of transmission (i.e a common ancestor). This assumption is support ed by a high Retention Index (0.7) (see graph 11). Besides, the two groups – A and B – as presented in the textual tradition clearly appear. The Neighbor-Joining Tree provides more information – (see graph 7). If we focus on the versions which seem the most related:

• For this episode, Yule took his material from FG – which we knew already.

• Ramusio’s tale being based on Z manuscript is not surprising, for it was one of his alleged sources.

• M and G are close and related to P, for they are remote translations of P.

• What seems new is that GA – from group A – had common points with L (from group B). This is due to the fact that neither of these versions mention The Miracle of the Mountain.

The Column

This episode appears a few chapters after the Miracle of the Mountain. The story takes place in Samarkand where a church has been built in the honour of the local Christian ruler. To achieve it, a part compos ing the central pillar was taken from the Saracens. The latter ask to have it back as soon as the ruler dies. Against all odds, the church remains stable and doesn’t collapse after the basement of its central pillar was removed. Human architectural wonder or God’s will? According to the versions, the answer varies a lot:

• Z – in which the tale is omitted – stands apart from the rest of the versions.

• TA decides for a wonder (in which God is not ne cessarily involved).

• P, V, L, and R remain cautious and just mention that the column stands without support of any human hand.

• G, FG, and Y favour an intervention of God, and state that the church remains thanks to God’s will.

• F and VB are the only versions to declare explicitly it is a miracle.

• Z – in which the tale is omitted – stands apart from the rest of the versions.

• TA decides for a wonder (in which God is not ne cessarily involved).

• P, V, L, and R remain cautious and just mention that the column stands without support of any human hand.

• G, FG, and Y favour an intervention of God, and state that the church remains thanks to God’s will.

• F and VB are the only versions to declare explicitly it is a miracle.

The group of close versions – FG, Y and F – is main tained but TA seems to have more in common with F this time (see graph 8). Their chapter headings are very similar, even if the story is more developed in F (442 words) than in TA (270 words). The story of the column appears between the same chapters in the manuscripts, and they locate and date the events in the same way. The general layout is alike but their content differs. They divide on figures – how many Saracens came to the church to have their stone back or how high the column lifted in the air is uncertain. Names vary as well – who the people were submitted to, which sovereign allowed the stone to be removed, and what family link he shared with Kublay Khan differ in the two versions. More striking is the interpretation of the episode: the story is considered as a miracle in F but as a wonder in TA – something incredible but not related to God’s will. The Neighbor-Joining tree may show some parent hood, but it is more due to formal characteristics of the text than to its content and meaning. P and G are still connected but their relationship is loose. R seems to have borrowed some material both from P and VA this time. In the Parsimony Tree, the relationships seen in previous episodes are no longer valid. It looks as if the versions of this episode were a deck of cards that were re-shuffled (see graph 12). Compared to The Miracle of the Mountain and St Leonard, the Retention Index (0.5) is lower here, which indicates a less important phylo genetic signal. Besides, the shape of the NeighborNet is less tree like (see graph 5). There are conflicting signals – boxes both elongated and square – which show contaminations between the versions. As a result, the chances that the versions didn’t share a unique ances tor are higher, and the intervention of the copyist greater.

Saint Thomas

Saint Thomas

The story takes place in India – in a city nearby what is today called Chennai – where St Thomas died. His body, kept in a church, is worshipped both by Christians and Saracens. Two sets of actions are attributed to the saint. One consists in healing people who drink a potion made with the red earth which surrounds the church. The second involves Saint Thomas himself who makes a death threat to a local ruler in his dreams causing him the latter to empty the church and the surrounding houses which were requisitioned to store a huge harvest of rice. The Parsimony Tree generated for this episode signals a lower Retention Index (0.5), which infers more contamination within the versions. As one can observe on graph 14, versions which are supposed to belong to different groups are strangely close.

• Ramusio borrowed more from P this time.

• L which usually stands apart as a version shows some parenthood with Z.

• TA-VB come as a surprise, so does the V-F rela tionship for they belong to different groups. This time the shape produced in the NeighborNet Tree is totally web-like, and indicates a higher level of con tamination (see graph 6). It seems that the tale has given rise to many interpretations and/or additions. For example, how St Thomas was killed is uncer tain. Was he hurt in the right side as F, FG, V and L suggest? Or in the left side favoured by VB? Or in the right leg as stated in Z? TA and R are even less precise: «on the side/on the sides». GA innovates when proclaiming that the red colour of the earth where St Thomas was buried was due to his assas sination in that location.

Conclusions

• Ramusio borrowed more from P this time.

• L which usually stands apart as a version shows some parenthood with Z.

• TA-VB come as a surprise, so does the V-F rela tionship for they belong to different groups. This time the shape produced in the NeighborNet Tree is totally web-like, and indicates a higher level of con tamination (see graph 6). It seems that the tale has given rise to many interpretations and/or additions. For example, how St Thomas was killed is uncer tain. Was he hurt in the right side as F, FG, V and L suggest? Or in the left side favoured by VB? Or in the right leg as stated in Z? TA and R are even less precise: «on the side/on the sides». GA innovates when proclaiming that the red colour of the earth where St Thomas was buried was due to his assas sination in that location.

Conclusions

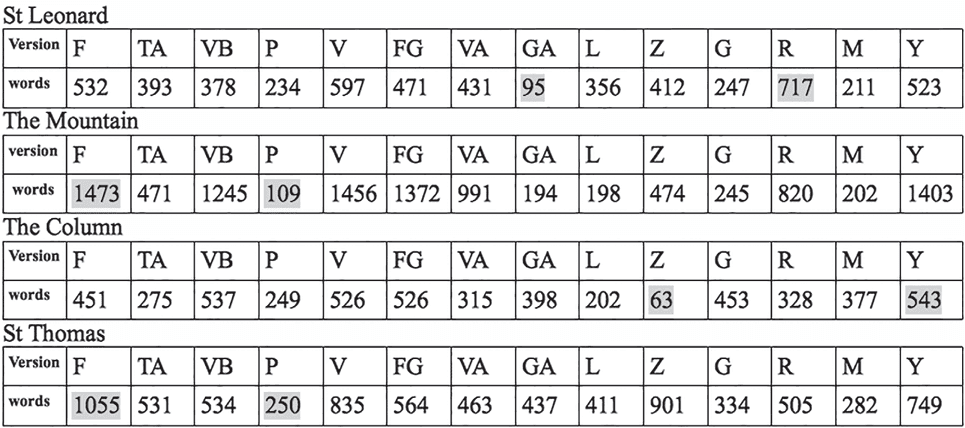

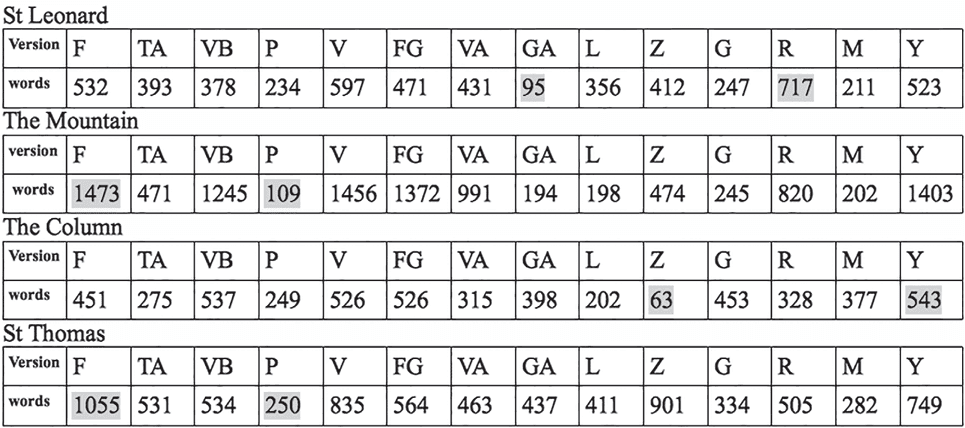

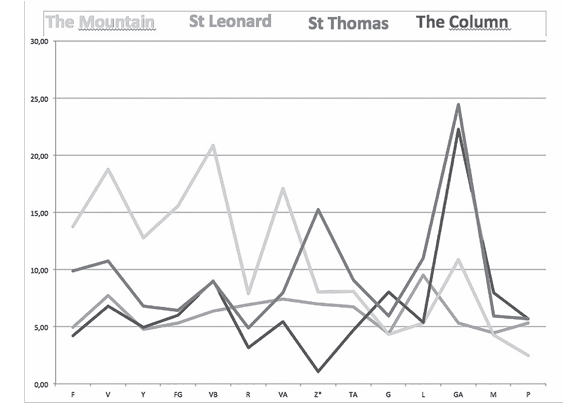

According to the versions of The Devisement du Monde, the miracles are not equally treated. They are sometimes included in a chapter and mixed with oth er elements, like in Ramusio’s version for St Thomas and The Miracle of the Mountain. They are sometimes singled out and have chapters purposely added and dedicated to it – like in VA for the miracle of St Leonard. On the contrary they can be omitted like in L for The Miracle of the Mountain or in Z for The Column. The role of the scribe and/or the political or religious issues are not to be excluded. As a matter of fact, the Latin versions tend to understate the selected episodes, either when they shorten the story like in P for the Miracle of Mountain and the miracle of St Thomas, or when they simply ignore it like in L for the Miracle of the Mountain, and in Z for the story of The Column. This might be explained by the fact that these tales were probably passed on to Marco Polo by Nestorian priests, and that this branch of Eastern Christianity was regarded as heretic in Western Europe. The total amount of words allocated to the stories plainly shows the importance given to each episode. According to the episode, they can vary from 3 to 13 times! (See tab. 1 and graph. 15).

Tab 1: Number of words by episode per version.

Tab 1: Number of words by episode per version.

Graph. 15. Number of words related to miracles for 1,000 words per version.

The topic of miracle is consequently not consistent. Its treatment depends on the versions and varies with time. Among the miracles, the most popular is The Miracle of the Mountain, and the least popular is St Leonard. GA, despite being the shortest version, dedicates more words describing these miracles than any other version, which reveals a real interest from the copyist for that topic, who sometimes innovates in the narrating. The similarities with Hayton’s Fleur de l’Orient, which was used as an incentive to set up an ultimate crusade in the near-East are troubling but out of our field of study.

In a multi-language context, the use of digital methods has proved particularly well founded, and neglected ethnographic aspects of Marco Polo’s narrative were underlined. Thanks to phylogenetic methods, it was possible to produce graphs showing that the copyists had at their disposal copies of different versions. Had they not, the general pattern of the graphs for each episode would had looked similar and they are clearly not. The use of different versions then explains the high level of contamination of versions depending on the stories. The copyists probably had at hand a Latin version (Z, L or P) when writing their own version of The Devisement du Monde. This is the case for Ramusio whose work is known as a compilation, but also for GA. In those cases, the different choices made when (re-)writing Marco Polo’s accounts were revealed.

The graphs generated by SplitTree4 and PAUP4 have highlighted unexpected similarities between some versions. In those cases, similarity was based both on the general layout and formal aspects (chapter headings, location in the narrative, spelling) and the content (meaning and interpretation). The variations, whatever they are, are given the same importance. Maybe the meaning of the text should prevail on formal aspects in order to minimize the risk of errors or misinterpretation.

The tale which presents the best tree-like shape is The Miracle of the Mountain. Its structure and content may have directly derived from the original missing manuscript dictated by Marco Polo to Rustichello. On the other hand, the most contaminated story is Saint Thomas. What to think of the numerous variations depending on the versions? Was the story really part of the original MS. or was it conveniently added and then re-written according to the specific needs of times. Whatever the answer, phylogenetics has pro vided some nuances to Marco Polo’s text tradition. At a time when some scholars are questioning the current classification, this approach offers new perspectives [31].

Sources

Sources

F = Ms. 1116 de la Bibliothèque Nationale de France. FG = Ms. Royal 19 D. I de la British Library. L = Ms. C1 della Biblioteca Comunale Ariostea. P9 = B.N Vienna, B.Pal. 3273. PI1 = Book of Lismore, Chatsworth House, Derbyshire. TA2 = II.IV.136 della biblioteca Nazionale di Firenze. V1 = Ms Ham. 424, Deutsche Staatsbibliothek, Berlin. VA3 = Ms. CM 211 della biblioteca civica de Padova. VB = Ms. 224 Museo Correr. Z = 49, 20 della Biblioteca Catedral de Toledo. G = Groulheau, Estienne, La description géographique des provinces & villes les plus fameuses de l’Inde orientale, meurs, loix, & coutumes des habitans d’icelles, mesment de ce qui est soubz la domination du grand Cham Empereur des Tartars, par Marc Paule gentilhomme Venetien, et nouvellement réduict en vulgaire françois, Paris, Groulheau 1556. M = Müller, Eugène, Deux voyages en Asie au XIIIe siècle par Guillaume de Rubruquis, envoyé de Saint Louis et Marco Polo, marchand Vénitien, Paris, Delagrave 1888.

Digital Editions

Digital Editions

F, L, P9, R, V1, VA3, VB = Digital edition, 2015. TA2= Biblioteca Italiana. Digital edition, 2003. PI1 = CELT Corpus of Electronic Texts, University College Cork, 1997. Cork: University College, 1997-present. G = Groulheau, Estienne, Digital edition. “Le Devisement du monde -Au Seigneur de Courlay,” Wikisource. M= Müller, Eugène. Digital edition.

Critical Editions

Critical Editions

Z = Barbieri, Alvaro, Milione: redazione latina del manoscritto Z, Parme, Fondazione Pietro Bembo - Ugo Guanda 1998. VB = Gennari, Pamela, Ph.D. Diss., Ca’ Foscari University of Venice 2009. P = Gil, Juan, trans., El libro de Marco Polo, ejemplar anotado por Cristobal Colón y que se conserva en la Biblioteca capitular y colombina de Sevilla, Madrid, Coleccion Tabula Americae 5, ed. Testimonio 1986. FG = Ménard, Philippe, Le Devisement du Monde, six volumes, Genève, Droz 2001-2009. F = Ronchi, Gabriella, Le Divisament dou Monde, Milan: Mondadori 1988. TA2 = Ronchi, Gabriella, Il Milione, Milan, Mondadori 1988). Y = Yule, Henry, The Travels of Marco Polo, The Complete Yule-Cordier Edition, vol. 1 & 2, New York, Dover Publications 1993.

References

References

Howe Christopher J., Barbrook Adrian C., Spencer Matthew, Robinson Peter, Bordalejo Barbara, et al. Manuscript evolution, in «Trends in Genetics» 17, 3 (2001), pp. 147-52

Huson, Daniel, Bryant David, Application of Phylogenetic Net works in Evolutionary Studies, in «Mol Biol Evol» 23, 2 (2006), pp. 254-267. Huy d’, Julien, A phylogenetic approach of mytho logy and its archaeological consequences, in «Rock Art Rese arch», 30,1 (2013), pp. 115-18.

Mayaffre, Damon, De la lexicométrie à la logométrie, hal.archivesouvertes.fr/docs/00/55/.../18_Mayaffre_Astrolabe_2005.pdf

Morrison, David, Introduction to Phylogenetic Networks (2012). http://acacia.atspace.eu/Tutorial/Tutorial.html#Intron.

Swofford, David L., PAUP* 4. Phylogenetic Analysis Using Parsimony (*and Other Methods). Version 4. (Massachussetts: Sunderland, Sinauer Associates, 1998).

Roos, Temu and Heikkilä, Tuomas, Evaluating methods for com puter-assisted stemmatology using artificial benchmark data sets, in «Literary and Linguistic Computing» 24 (2009), pp. 417-33.

Tehrani, Jamie, The Phylogeny of Little Red Riding Hood, in «PLoS ONE» 8(1): e78871, 2013.

Notes

Notes

1. L. Foscolo Benedetto, Marco Polo, Il “Milione”, prima edizione integrale, Florence, Olschki 1928.

2 C. Wagner Dutschke, Francesco Pipino and the manuscripts of Marco Polo’s Travels, Ph.D. Diss., University of California, Los Angeles 1993.

3 D. Mayaffre, “De la lexicométrie à la logométrie” hal.archive souvertes.fr/docs/00/55/.../18_Mayaffre_Astrolabe_2005. pdf

6 FG = MS. Royal 19 D. I, British Library, London. Philippe Ménard, Le Devisement du Monde, Genève, Droz 2006 2009), t. 1 to t. 6.

7 TA = MS. II. IV. 136, Biblioteca Nazionale Centrale, Firenze. (Biblioteca Italiana, 2003), digital edition.

8 VA = CM 211, Biblioteca Civica, Padova. A. Barbieri, A. Andreose, Il “Milione Veneto”, Venice, Marsilio 1999.

9 P = Copy annotated by Christopher Columbus, conserved at the Capitular and Columbus Library of Sevilla, J. Gil, trans., Marco Polo, Madrid, Testimonio 1986.

10 Yule opined the division into three books didn’t originate with Pipino for another older Latin version presented the same characteristic. (old Latin version 3195 of the Paris BnF). https://ebooks.adelaide.edu.au/p/polo/marco/travels/intro duction.html#section10

11 B. Wehr, «À propos de la génèse du Devisement du Monde», in Le passage à l’écrit des langues Romanes, ed. M. Selig, B. Franck and J. Hartman, Tübingen, Narr, 1993, pp. 299-326.

12 GA = PI1, known as “the Book of Lismore”, Lismore Castle, Chatsworth House, Derbyshire. Edition translated in English, (Cork: University College, 1997-present) CELT: Corpus of Electronic Texts, http://www.ucc.ie/celt/online/T305002/

13 G = Estienne Groulleau, trans., La description géographique des provinces & villes plus fameuses de l’Inde orientale, meurs, lois, & coustumes des habitants d’icelles, mesme ment de ce qui est soubs la domination du grand Cham empereur des Tartares, par Marc Paule gentillhomme Venitien, et nouvellement réduict en vulgaire françois (Paris: 1556).

14 This text was based on Grynaeus Novus Orbis – a Latin copy of a Portuguese version of The Devisement du Monde. The latter was translated from P, which was a translation of a Venetian version!

15 M = Eugène Müller, trans., Deux voyages en Asie au XIIIe siècle par Guillaume de Rubruquis, envoyé de Saint Louis et Maro Polo, marchand Vénitien, Paris, Delagrave 1888). Was also based on Grynaeus Latin copy with a collation of readings from the Pipino MS.

16 Z = MS. 49, 20, Biblioteca Catedral, Toledo. Alvaro Barbieri, «Milione». Redazione latina del manoscritto Z, Milano, Fond. Pietro Bembo - Guanda 1998.

18 Christine Gadrat-Ouerfelli, Lire Marco Polo au Moyen Âge, Traduction, diffusion et réception du Devisement du monde, Turnhout, Brepols, Terrarum orbis 12, 2015, p. 106.

19 V = MS. Hamilton 424, Deutsche Staatsbibliothek, Berlin. Samuela Simion, Il «Milione» secondo il manoscritto Hamilton 424 della Staatsbibliothek di Berlino. Edizione critica, PhD. Diss., Ca’ Foscari University of Venice 2008.

21 VB = MS. 224, Dona dalle Rose, Museo Civico Correr, Venice. P. Gennari, «Milione», redazione VB. Edizione critica commentata, PhD. Diss., Ca’ Foscari University of Venice 2009.

23 R = Giovani Batista Ramusio, Navigationi e viaggi, vol. II, 1559. E. Burgio, M. Buzzoni and A. Ghersetti, Digital Edition, 2015 http://edizionicafoscari.unive.it/col/exp/36/61/Filologie Medievali/5

24 Y = Sir Henry Yule, The Travels of Marco Polo, The Complete Yule-Cordier Edition, vol.1, New York, Dover Publications 1993.

27 For more details about this method, see D. Huson and D. Bryant, Application of phylogenetics Networks in Evolutionary Studies, in «Mol Biol Evol» 23 (2, 2006): 254-267, doi: 10.1093/molbev/msj030. As examples of phylogenetics applied to Digital Humanities, see J. d’Huy, A phylogenetic approach of mythology and its archaeological consequences, in «Rock Art Research», 30 (1, 2013), pp. 115-11. Howe Chistopher J., Barbrook Adrian C., Spencer Matthew, Robin son Peter, Bordalejo Barbara et al., Manuscript evolution, in «Trends in genetics», 17, 3 (2001), pp. 147-52.

28 D. Morrison, Introduction to Phylogenetic Networks (2012): http://acacia.atspace.eu/Tutorial/Tutorial.html#Intron.

29 Right and left have no particular meaning. What matters is the length of the lines between two versions: the shortest the closest.

30 D.L. Swofford, PAUP* 4. Phylogenetic Analysis Using Par simony (*and Other Methods). Version 4. (Massachussetts: Sunderland, Sinauer Associates 1998).

31 E. Burgio, S. Simion, Un’edizione moderna del milione nelle carte inedite di Luigi Foscolo Benedetto, in «Quaderni Vene ti», 2. (2013), pp. 59-70.

¬ top of page