« indietro

Manzoni’s Electronic Interpretations

di Claudia Bonsi,

“Sapienza” Università di Roma, claudia.bonsi@yahoo.it

Angelo Di Iorio,

Univerisità di Bologna, angelo.diiorio@unibo.it

Paola Italia,

paolaitalia3@gmail.com

Fabio Vitali

Università di Bologna, fvitali@gmail.com

Abstract:

The case study of the famous Italian Alessandro Manzoni’s novel: I Promessi Sposi / The Betrothed, and its complicated history of different writings, due to the author’s searching for a real Italian Language, has given La Sapienza’s researchers group the idea that every critical lecture may be a marking of text and leaves on the text a sign of its passage. Using a brand new informatic platform derived from European differences in law proposals, the research group has developed PhiloEditor 2.0, a tool that students, scholars and teachers may use to apply their critical categories to the text online, sharing with other students, scholars and teachers their critical hypothesis, checking each other the rightness of markers. With PhiloEditor® 2.0 students can mark texts without computer skills, for learning and scientific purposes, annotating phenomena by choosing between a range of existing annotations – after turning to the traditional tools of literary studies – and connecting elements of different chapters that belong to the same category or methodology of correction, leaving a sign of a non-mechanical reading made with mechanical methods.

1. Digital Ecosystem Innovation for Scholarly Editions

1. Digital Ecosystem Innovation for Scholarly Editions

If we agree that «the Internet ecosystem does not only provide new channels for making available editions originally disseminated in printed format but, more important, pushes a real change of methodology in the interpretation of a text» [1], a Digital Ecosystem brings a brand new innovation for Scholarly Editions, because it changes all the basic elements of a Textual Environment, which we can list in Time, Space, Form and Social.

Each of these categories must be explained to understand the great changes in representing changing texts, especially texts we can study through their manuscripts:

1 TIME: Diachronic Text. Digital Scholarly Editions may give a synoptic view and a diachronic representation of the variants: all the changes may be represented, and their diachronic relationship may be easily shown. Despite the importance of the chronological asset, most of the Digital Scholarly Editions are Diplomatic, and not Critical, that is to say that they don’t represent the different phases of the genesis of texts, but only the transcription of the variants and their position in space.

2 SPACE: All the texts. The topographic aspect is emphasized due to a clearer representation and a larger available space, with important consequences also in the ecdotic field: the possibility to publish all the witnesses brings a crisis of the traditional philology, and a sort of ‘Bédier effect’: someone believes that it is better to publish many different real editions/manuscripts rather than make an effort to do a reconstruction of a hypothetic text.

3 FORM: Iconic Text. The digital scholarly edition is based much more on its iconic representation rather than on a series of abbreviations and explanations, and has a deep relationship with the imaging of text. Sometimes the imaging of text is considered the edition itself, the critical edition.

4 SOCIAL: the «Wiki text». The greatest change in Scholarly Edition related to the Digital Environment is the collaborative and participating way of working, due to the specific characteristic of the web, after the revolution of the Social Network: the edition is not the scientific achievement of a single scholar, but a collaborative action on the web. It is not the result of a single philological choice, but a collective sum of choices, none of which plays a former role, brings the responsibility as a critical editor of the text. The reader is not only a passive user of the text: the reader is the scholar. This latest change is the biggest revolution in Scholarly Edition. It’s something similar to the great changes due to the Wikipedia way of building the biggest Encyclopedia on the web. Two projects can easily show the methods and the results of this new way of editing text: the project of Transcribe, Bentham Manuscripts, case study of http://transcriptorium.eu/ and https://transkribus.eu/Transkribus/ according to the idea that «everyone can make a valuable contribution to scholarship and science» (https://transkribus.eu/ Transkribus/#download). In this environment, but following a different way of working, the sharing platform WIKI GADDA (www.filologiadautore.it/WIKI) leads to the Italian Way to a collaborating a sharing philology. WIKI Gadda is a Scientific Project lead by Sapienza University and other University Partners (Siena University, Parma University, Pavia University), made by scholars and students following close ecdotic criteria, aimed at working together on a digital platform, but correcting each other under the guide of specialists.

If we consider texts born in the analogic era, texts coming from Gutenberg time and driven towards Google time, we can conclude that digital environment provides us with a new layout to visualize texts, new tools to analyse them, new methods to explain and understand them [2], but, according to Thomas Tanselle, it doesn’t change the ontology of a text. Moreover the idea that reading it on a screen leads to a different way to read and analyse texts goes too far: «the computer is a tool, and tools are facilitators; they may create strong breaks with the past in the methods of doing things, but they are at the service of an overriding con tinuity, for they do not change the issues that we have to cope with» [3].

What is evident is the richness of the way in which a Scholarly Edition can exist on the web, but the process to make the Scholarly Edition itself doesn’t depend on the digital environment, but comes from a scientific knowledge of the text. Almost twenty years ago, an old up to date XX Century philologist, Domenico De Robertis, tried to represent Leopardi’s variants on the web with a basic and rough tool which illustrated manuscript variants in their transition from one edition to another [4]. What he did, his philological pioneering attempt is not old fashioned at present. What is old fashioned is the digital tool he used, as his web site is no more active, the link doesn’t work anymore.

2. Digital Ecosystem Innovation for Scholarly Interpretations

2. Digital Ecosystem Innovation for Scholarly Interpretations

The same basic elements examined before may be analyzed from another point of view, i.e. the interpretation of the text. From this point of view, the digital environment is much more impactful on the way to study texts, and for their interpretations, because it is rapidly evolving towards the Semantic Web, which provides us with useful technologies to represent what is not on the surface of the texts: its content, language and style, but what is implicit in a series of relationship inside the text: the ‘unsaid’ of the text. As Francesca Tomasi wrote, under the Scholarly Edition, is the «Digital Scholarly Infrastructure: texts, services, and instru ments to use text and paratext» [5]. It’s facing all these new problems that we will be able to use the challenge of Semantic web in a wonderful hermeneutic opportunity, developing tools which may help us to connect, in a digital environment, all the dimensions of texts.

TIME. Diacronic Text. In the Digital Ecosystem text isn’t anymore an entity, unbound from its chronotope, but is to be understood in its time and diachronic variants: text is inside its history rather than out of time and history.

SPACE. All the texts. The immediate relationship with other texts written by the same author, or similar texts written by different authors, leads to a topographic interpretation of the text, a new light on its place in the literary space, which, much more than before, is related and connected.

FORM. Iconic Text. It’s easy to prove the iconic interpretations and relationship with the imaging of text given by its Web life. The real essence of a Web Scholarship Edition is a representation of its iconic shape, from the manuscript of the text to the first print, to the reprinting and new editions which may have changed its shape. The iconic interpretation is not only related to the philological aspect of the text, but also to its figurative aspect: the hermeneutic action goes through its iconic life.

SOCIAL. Wiki texts. Also the critical aspect may be changed by the Web environment, especially on its social side. After having a big collection of Scholarship Editions of Manuscripts and Text, it is necessary to study them, and is impossible to do it without sharing knowledges, methodologies, points of view. Since we have collaborative & participating editions, so we have collaborative & participating interpretations: the reader is not only an editor but is the critic.

As the sharing ecdotic may be out of scientific con trol, it is necessary to give some precise guidelines not to make a superficial and unscientific transcription of text [6], so the critical action may be out of critical control, and go into an amount of personal point of views, angry debates among ideological ideas, or even places of personal struggle for narcissistic performance. As the Italian way to WIKI Edition is a community of scholars guided by specialists, the same happens with a Wiki Critical Analysis: not a Blog of criticism around a text, guided by speed and exhibitionism, but a slow training sharing platform of participating in critical lectures, guided by specialists on Literature, Linguistic, Narratology, Comparative Literature, etc.

3. A (non) mechanic reading: Manzoni’s PhiloEditor 2.0.

3. A (non) mechanic reading: Manzoni’s PhiloEditor 2.0.

The mechanic reading we have developed with PhiloEditor 2.0 has a basic starting point: the idea that every critical lecture may be a marking of text, leaves on the text a sign of its passage, as a new painting gives a new face to the wall it has painted. With Philoeditor 2.0 students, scholars and teachers may apply their critical categories to the text on line, sharing with other students, scholars and teachers their critical hypothesis, checking each other the rightness of markers, and so on.

The case study is the famous Italian Alessandro Manzoni’s novel: I Promessi Sposi / The Betrothed.

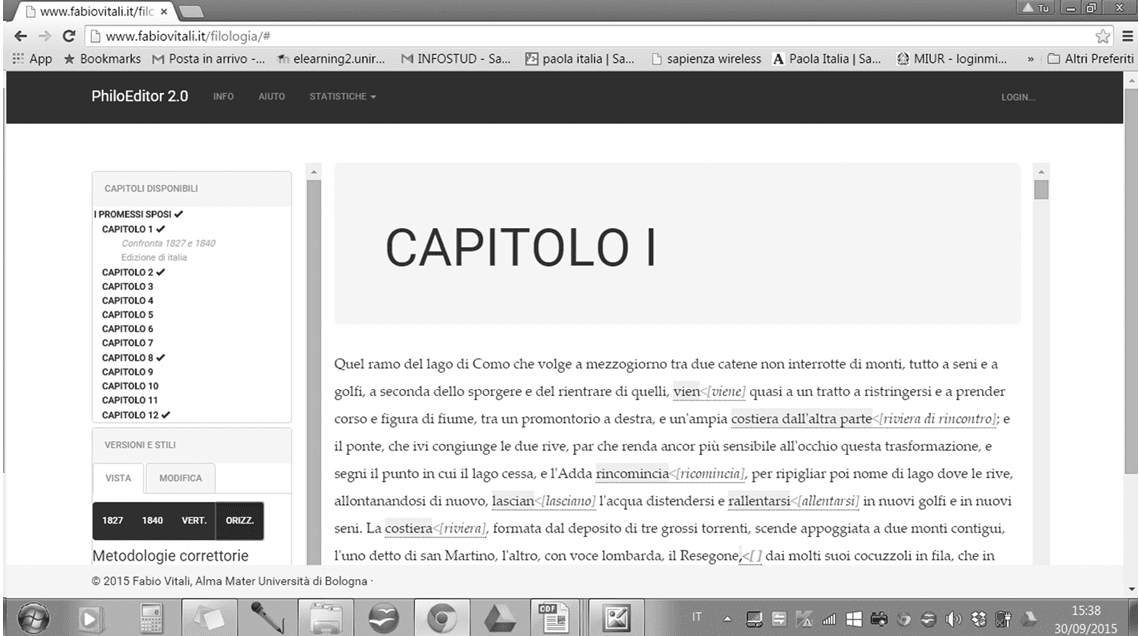

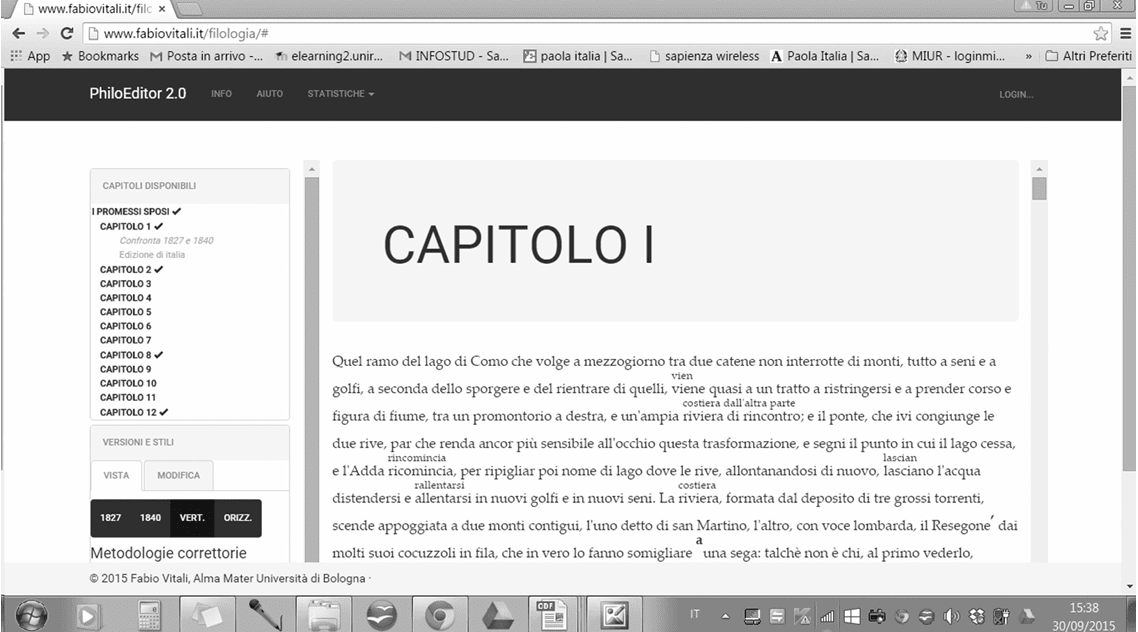

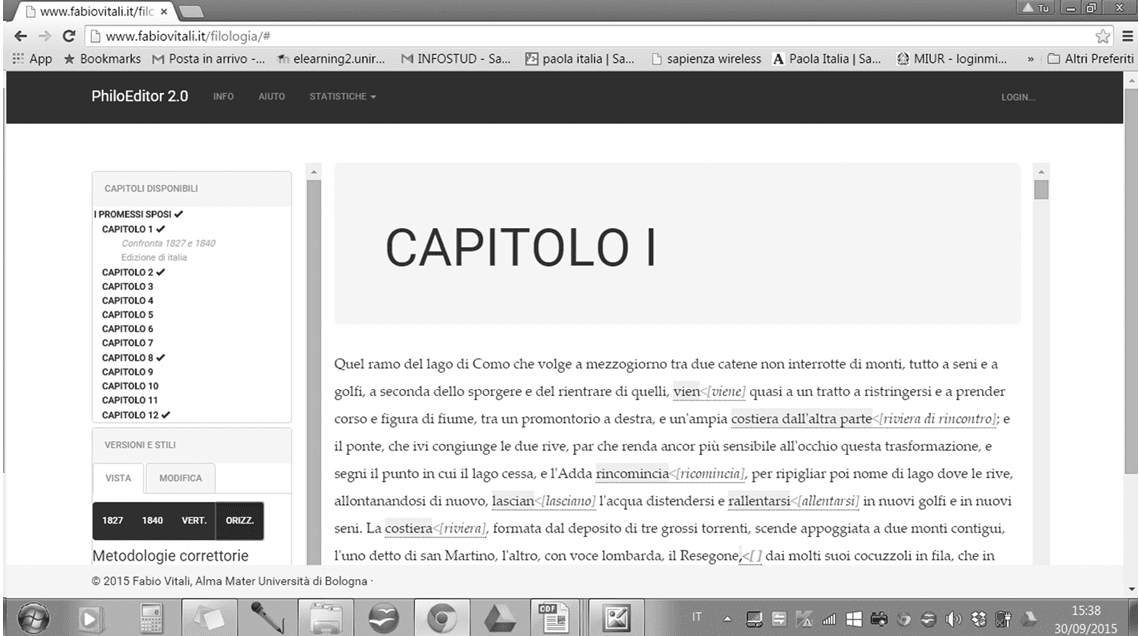

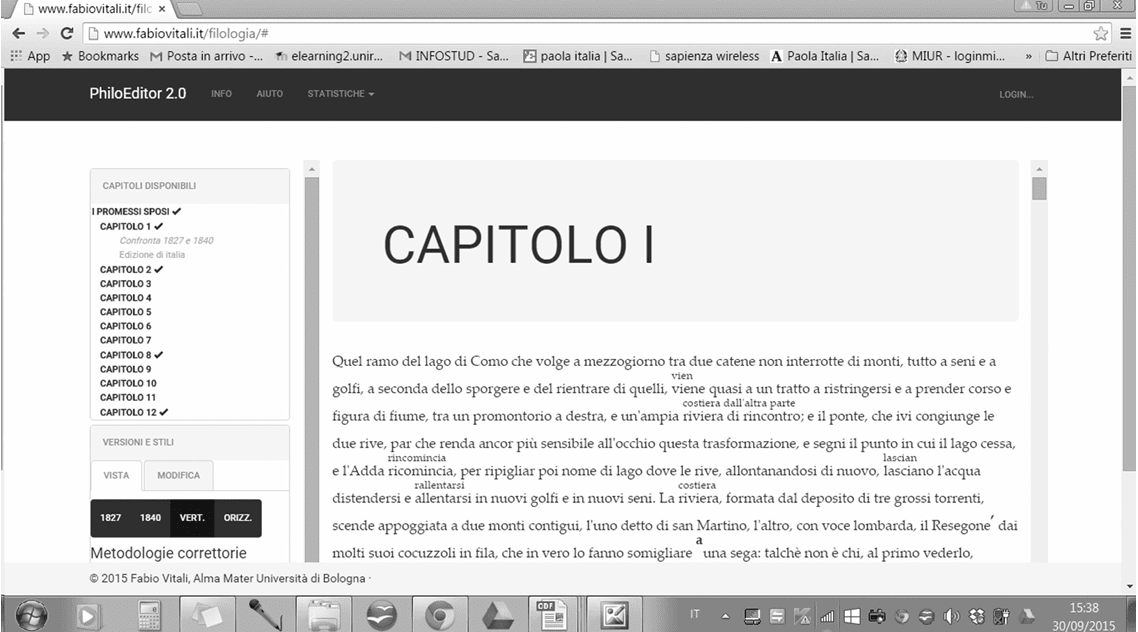

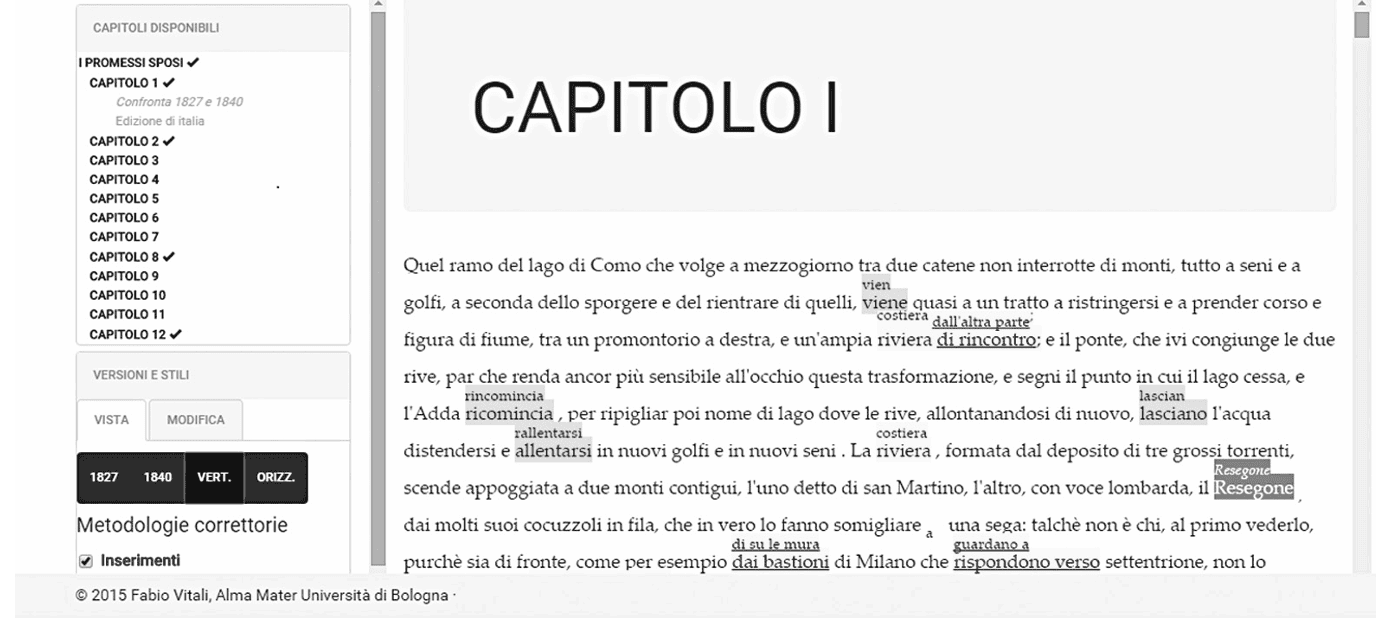

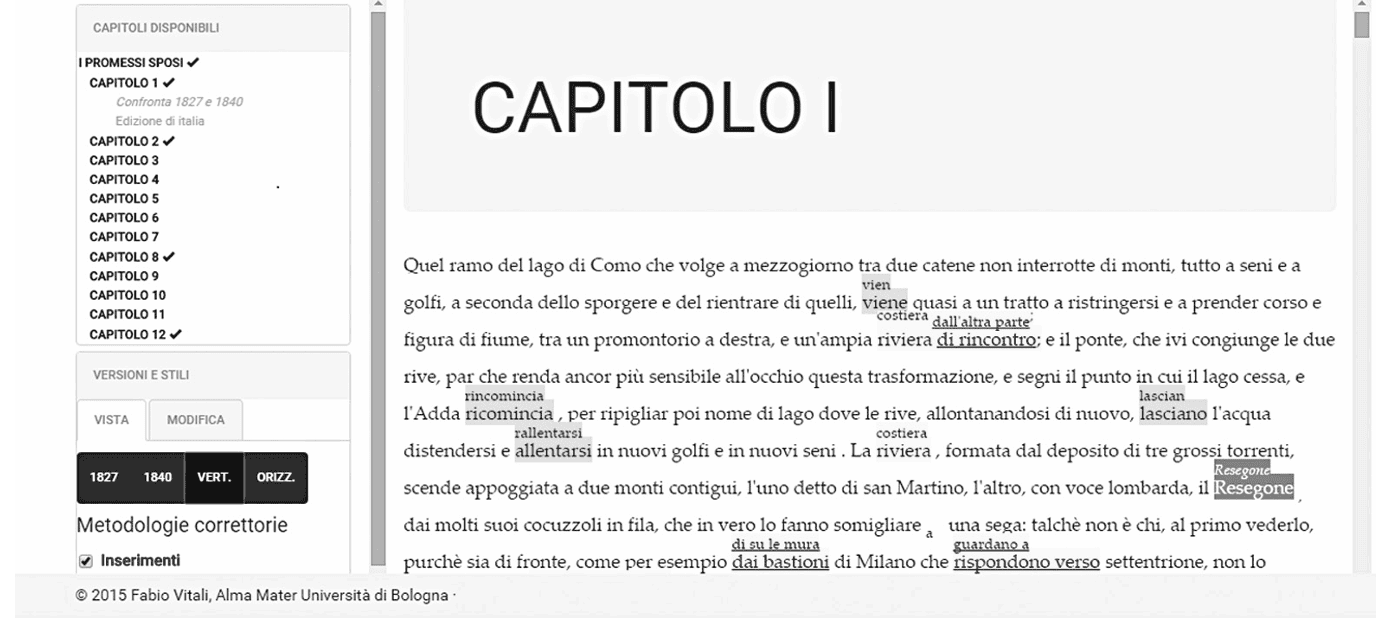

Why The Betrothed? Because it’s the most relevant novel of the Italian Literature, it was subjected to a continuous and long elaboration (both textual and linguistic) from 1821 to 1840; it’s a grounding source not only for the Italian novel but also for the current Italian language and it’s a primary case study of a didactic tool for a non mechanic reading with mechanic instruments on a mandatory textbook in the Italian Secondary school. Moreover, Manzoni made some specific linguistic and stylistic corrections, not structural ones, to change the language towards a Tuscan-Florentine spoken language, and these corrections are easily represented. Philoeditor 2.0 provides a mechanic comparison of the texts and gives a visual representa tion in a horizontal (Fig. 1) or vertical way (Fig. 2).

It isn’t a complete mechanic analysis, just because no complete mechanic analysis may be done without an individual control: the best mechanic reading of a text is the one which needs a human government. And it needs a previous training on the critical categories you want to recognize in the text: be they linguistic (as for Manzoni’s The Betrothed, because of its specific genetic history), stylistic, narrathological, anthropological categories, and so on.

Fig. 1. PhiloEditor 2.0, Horizontal View of The Betrothed, Chap. 1.

Fig. 2. PhiloEditor 2.0, Vertical View of The Betrothed, Chap. 1.

Fig. 1. PhiloEditor 2.0, Horizontal View of The Betrothed, Chap. 1.

Fig. 2. PhiloEditor 2.0, Vertical View of The Betrothed, Chap. 1.

As we have already shown [7], PhiloEditor 2.0 is a web-based environment for reading texts in a synchronic and diachronic way, annotating their variants and marking linguistic and stylistic phenomena. So its functions are not only philological but also critical and hermeneutic: the GAE: Genetic Analytic Editions provides not only a text-to-read but a text-to-comment.

PhiloEditor 2.0 may be used in two different modali ties: reading mode (VISTA) and edit mode (MODIFICA).

READING MODE (VISTA). The reading mode changes the way of viewing texts on the web: from a synoptic mode (texts side by side) to a stratigraphic representation (texts overlapped); from a taxonomy of variants to a deep study of texts, and from a plane view to a stereoscopic and collaborative reading of texts, useful in a didactic perspective. Colors and typographic elements easily mark linguistic and stylistic phenomena.

EDIT MODE (MODIFICA). The edit mode allows the reader to become a critic, creating new annotations. The reader re-organizes the text where differences exist between the two versions, assigns a category to each annotation, saves annotations so that are available when the document is re-loaded [8].

While PhiloEditor 2.0 detects automatically the differences between the two variants, the reader gets from GAE – marking the text – all the information about his specific interests: linguistic, historic, theoretical, etc. The tool shows the variants to the reader in two alternative views: horizontal or vertical, for displaying the same change, while the reader can mark changes, classify variant and propose his own analysis of the text. In Manzoni’s case study we have marked methodological corrections (order of words, corrections to avoid repetitions, systemic corrections, phraseological corrections), which are formatted with different colors and linguistic corrections (deletions of literary words, tuscanisations, allotropy, truncation, elision, monoph thongization, graphical corrections, punctuations) formatted with a colored background, so that such a classification can co-exist with the methodological one, and avoid the problem of overlapping.

4. PhiloEditor 2.0: Mechanic quantitative analysis

4. PhiloEditor 2.0: Mechanic quantitative analysis

PhiloEditor 2.0 helps users in marking multiple phe nomena on the same text. The possibility of sharing and editing such annotations is one of the key aspects of the tool: scholars can apply different analyses on the same text, compare overlapping or conflicting analyses, edit previous annotations, and so on. To support this, PhiloEditor 2.0 integrates an access control manager: users can login into the system and, if they have write permission, can add annotations and save these annotations in a shared and controlled workspace. Each annotated variant is associated to an author and can be easily accessed by all others.

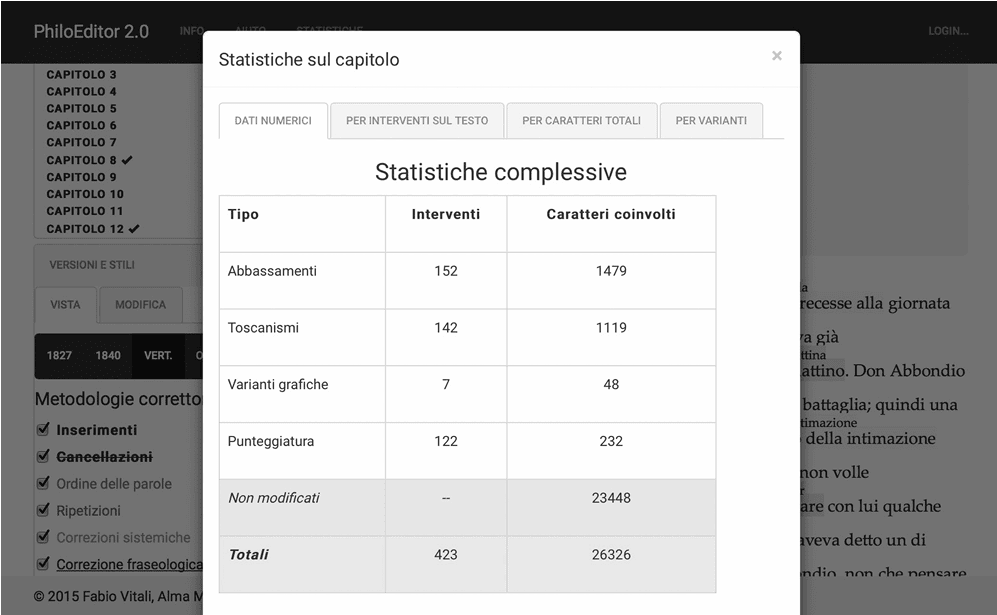

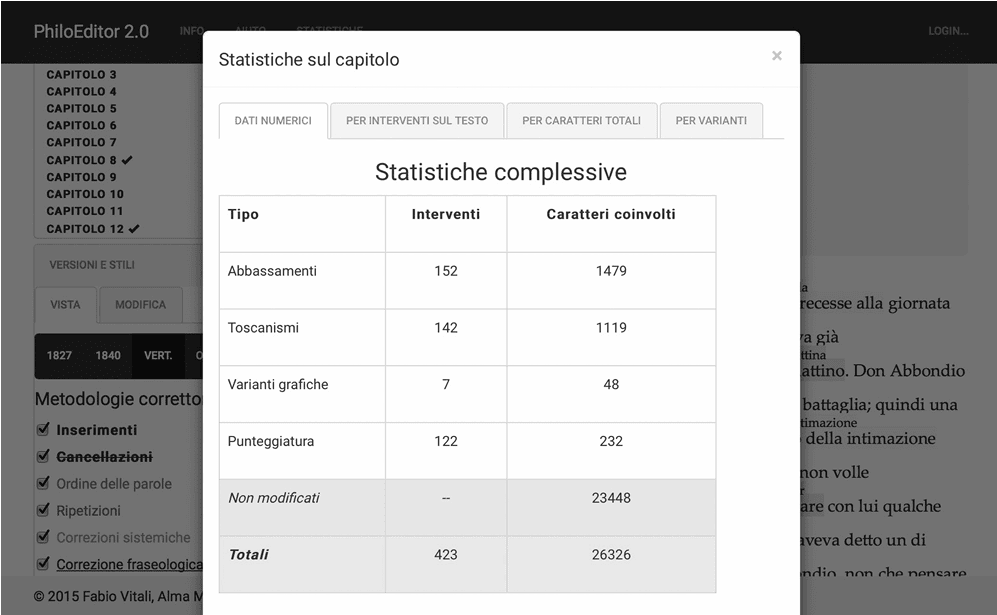

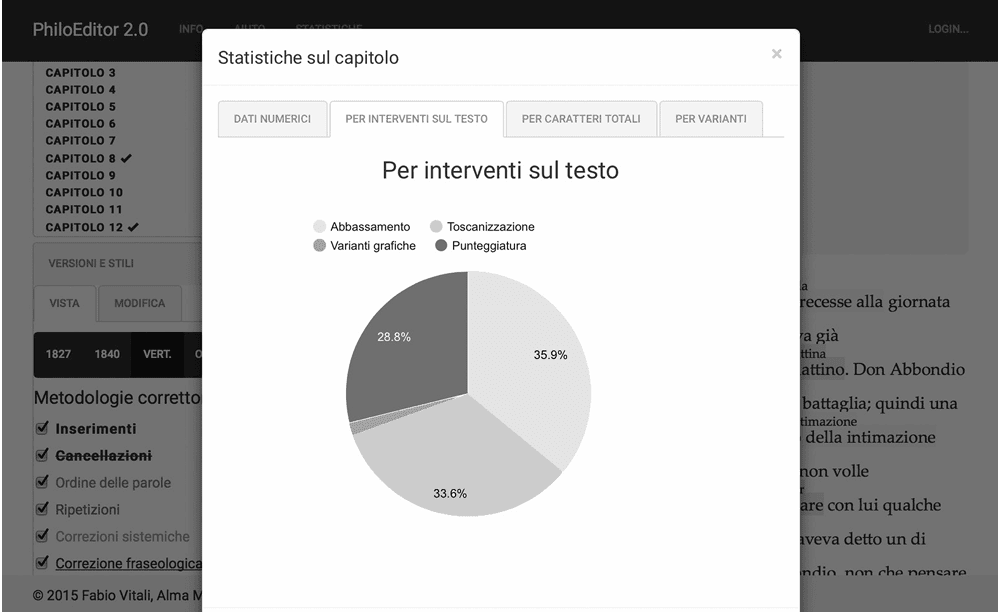

Besides studying annotations directly on the text, it is helpful for scholars to have a global view of what happened on a document. Towards this goal, PhiloEditor 2.0 provides a tool that aggregates and summa rizes data about all corrections identified by the users. The tool can be easily opened from the menu area. It opens a popup window, where users can find aggre gated data and charts. These data are calculated by counting the number of corrections on the input document and, for each correction, the number of charac ters affected by that correction. Corrections are also clustered by their type. Fig. 3 shows the first panel of the STATISTICS tool.

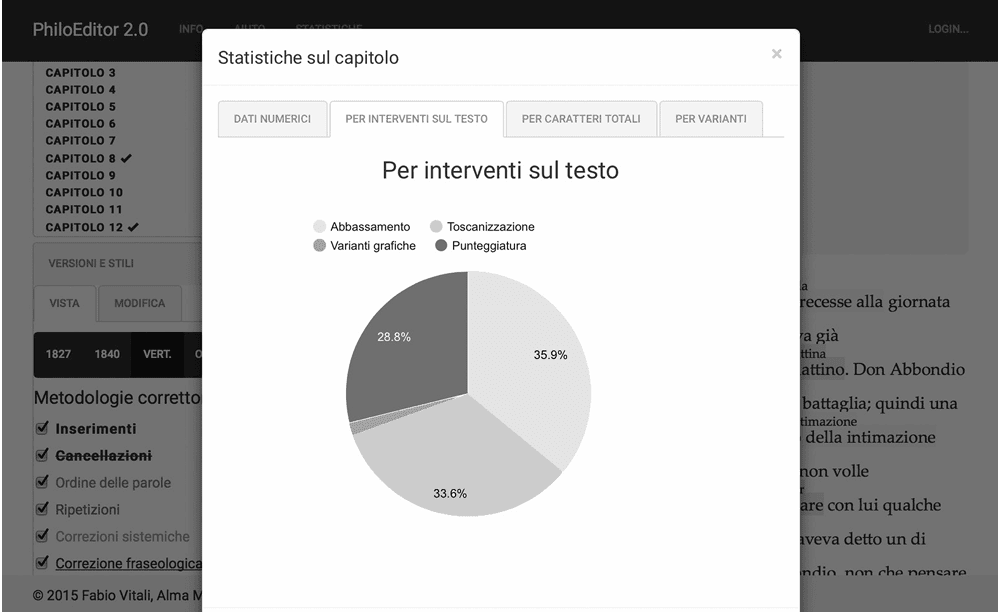

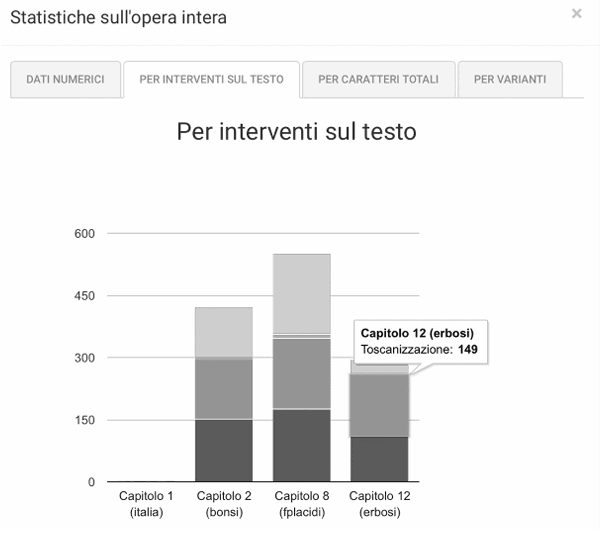

The panel shows general statistics about a chapter: the number of corrections and affected characters for the whole chapter (last row in the table) and the same data aggregated for each class of correction (first rows with white background). PhiloEditor 2.0 includes other three panels showing charts that summarize how corrections have been distributed in the chapter. In particular, these charts show: the percentages of each class of corrections (linguistic categories), the percentage of variants affected by each class and the percentage of affected characters. An example is shown in Fig. 4.

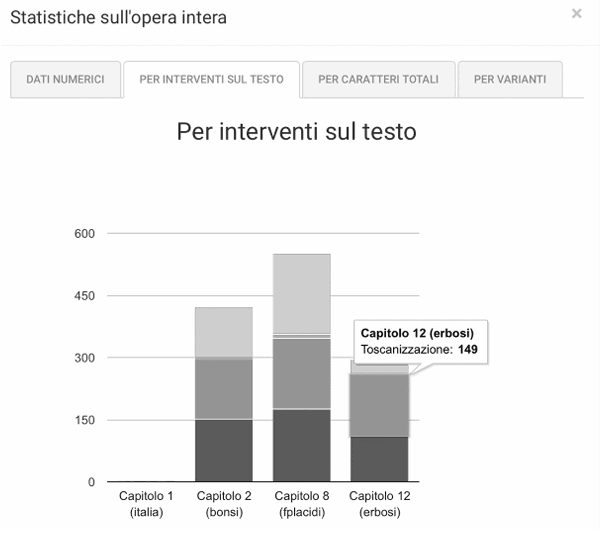

Finally PhiloEditor 2.0 allows users to access aggre gated statistics about multiple chapters, in an intuitive way that makes it easy to compare corrections inter- and intra-chapter. Data can be accessed in tabular form as well as in charts, as shown in Fig. 5.

The diagram shows the amount of text affected by each class of correction in each chapter. There is in fact one bar for each chapter, divided in four parts (one for each linguistic category). Labels and callouts have been added to help readers access each piece of information.

Fig. 3. Aggregated statistics about corrections in PhiloEditor 2.0.

Fig. 4. Charts showing distribution of corrections on a chapter in PhiloEditor 2.0.

Fig. 5. Charts showing distribution of corrections on multiple chapters of the same book.

5. A new methodology to study texts: didactic potentialities

Fig. 3. Aggregated statistics about corrections in PhiloEditor 2.0.

Fig. 4. Charts showing distribution of corrections on a chapter in PhiloEditor 2.0.

Fig. 5. Charts showing distribution of corrections on multiple chapters of the same book.

5. A new methodology to study texts: didactic potentialities

The potentialities of this new methodology are enormous: the focus on the dynamic nature of the text has not only a philological function but also a critical one, since the instrument allows multiple, overlapping and even conflicting ways of annotating variants and different phe nomena of text (linguistic, stylistic, nar rative). For these very reasons, Philoeditor® 2.0 can be fruitfully employed in teaching practice with students, who can test their critical and interpreting competence by marking the variants between two versions of the same text.

Actually, the prototype has already been exploited for the first time in a workshop held by professor Paola Italia at Sapienza University (Rome, a.a. 2014-2015) [9], involving undergraduate students of Italian literature and philology that have been given the possibility of using traditional tools in a digital environment, improving two different skills at the same time.

In the first phase of the workshop, the students have been introduced to the fundamental concepts of critica delle varianti, that I will briefly resume: while error can be defined as the estrangement from an established norm or as a deviation in a material copy of the text from the original text decided by the author – more or less meaningful –, in authorial philology a variant is the modification of something that already exists, a different form, expression or phase compared to another, meaningful, one (principle of the comparability of variants) [10]. Variants can be substantial (lexical, structural) or formal (graphic, phonetic, morphological). The philologist highlights the directions at which the corrections aim through the catalogation of variants (e. g. in crease/decrease of aulicisms, tuscanisation, increase of dialectalism, censorship/selfcensorship etc.), in order to obtain a characterising description of the style of each analysed work (synchronic approach) and to stress the movement of the style (diachronic approach). After that, the professor has opened a guided reflection upon the different possibilities of transferring the methods of critica delle varianti on a digital interface, representing and marking the dynamic dimension of the text in the most coherent and economic way possible [11]. As a matter of fact, one of the challenges issued by new digital technologies in the field of literary and textual studies is to find the most effective interaction between conventional and non-conventional ways of learning, in order to illustrate cultural, linguistic and literary concepts without losing anything in the passage from print media to virtual ones.

The second phase has been dedicated to the illustration of our case study, The Betrothed, which shows a system of small, discrete authorial variants between its two printed editions. As a matter of fact, Manzoni, after the analogic, ‘europeanised’ language employed in the first draft of the novel, Fermo e Lucia (1821-1823), publishes the first edition of the text, the so called ‘Ventisettana’ (1825-27) – which displays macrotextual and structural variants compared to Fermo e Lucia –, in a literary Tuscan language, taken from dictionaries and Tuscan authors. In the last and definitive edition of the novel, the so-called ‘Quarantana’ (1840-1842), the author eventually achieves his goal, patiently making punctual corrections – of single words or phraseological expressions – on a working copy of the ‘Ventisettana’: a novel written in Florentine, as it was spoken by cultivated Florentine people of his time.

At this point, each student has been given a chapter of the first volume of The Betrothed and has been asked to mark with PhiloEditor® 2.0 prototype – applied to the first twelve chapters of the novel – the text of the ‘Quarantana’, compared to that of the ‘Ventisettana’, associating to each couple of variants a methodology or a category of correction, or both, using the prearranged set of typographical and chromatic marks. We can take as an example the very first lines of chapter I.

Fig. 6. PhiloEditor 2.0, Stratigraphic View of The Betrothed, Chap. 1.

Fig. 6. PhiloEditor 2.0, Stratigraphic View of The Betrothed, Chap. 1.

Yellow is used to mark effects of stylistic lowering (riviera > costiera; dai bastioni > di su le mura; rispondono verso > guardano a), blue for cases of tuscanisation (viene > vien; ricomincia > rincomincia; allentarsi > rallentarsi), red forgraphic variants (Resegone > Resegone). At the same time, these categories of correction can be combined with the methodologies: indeed, some variants are also double underlined (dai bastioni > di su le mura; rispondono verso > guardano a), so as to point out the simultaneous presence of a phraseological correction. The interpreting action of the students is not obviously confined to ‘clicking the button’. In order to assign the right annotation to each couple of variants, they have had to retrieve the information concerning linguistic and stylistic phenomena by resorting to the traditional tools of literary research: dictionaries, such as the fourth impression of the Vocabolario della Crusca (Firenze, Domenico Maria Manni, 1729-1738, also available on line at http://www.lessicografia.it/), the Vocabolario milanese-italiano of Francesco Cherubini (Milano, Stamperia Reale, 1814), the Vocabolario dell’uso toscano of Pietro Fanfani (Firenze, Barbera, 1863), the Dizionario della Lingua Italiana edited by Niccolò Tommaseo and Bernardo Bellini (Torino, Pomba, 1861-1874), the Grande dizionario della lingua italiana edited by Salvatore Battaglia (Torino, UTET, 1961-2002); annotated editions of the novel, such as the latest edited by Teresa Poggi Salani (Milano, Centro nazionale studi manzoniani, 2013); the remarks written by Manzoni himself on his copy of the Vocabolario della Crusca (ed. by Dante Isella, Milano-Napoli, Ricciardi, 1964); studies on XIXth century literary language and on Man zoni’s literary production, such as the works of Luca Serianni and Maurizio Vitale [12].

Moreover, thanks to the handbook provided by PhiloEditor® 2.0, the students have been given the possibility to re-segmentate by themselves the variants wrongly generated by the diff, thus reflecting on the notion of textual unit according to the principle of the comparability of variants. Eventually, generating histograms and pie charts that show the relevance of every phenomenon, the students could actually see – and discuss in a composition written at the end of the workshop – the proximity, or the distance, between this quantitative representation of the novel’s language processing in its two printed versions and the specific bibliography on this topic.

As we have seen, with PhiloEditor® 2.0 students can mark texts without computer skills, for learning and scientific purposes, annotating phenomena by choosing between a range of existing annotations – after turning to the traditional tools of literary studies – and connecting elements of different chapters that belong to the same category or methodology of correction, leaving a sign of a non-mechanical reading made with mechanical methods.

Bibliography

Bibliography

Contini G., Come lavorava l’Ariosto [1937], in Id., Esercizi di lettura sopra autori contemporanei con un’appendice su testi non contemporanei, Torino, Einaudi 1974.

De Robertis D., «Il Coro dei morti nello studio di Federico Ruysch», in D. De Robertis, Genesi, critica, edizione, Annali della Scuola Normale di Pisa 1998, pp. 241-51.

Di Iorio A., Italia P., Vitali F., Variants and versioning between Textual Bibliography and Computer Science, Proceedings of the Third AIUCD Annual Conference on Humanities and Their Methods in the Digital Ecosystem, 2014 http://dl.acm.org/citation. cfm?id=2802614

Isella D., Le carte mescolate. Esperienze di filologia d’autore, Padova, Liviana, 1987 [new edition: Le carte mescolate vecchie e nuove, a c. di S. Isella Brusamolino, Torino, Einaudi 2009].

Italia P., Edizioni su web, un web per le edizioni, in Ead., Editing Novecento, Roma, Salerno Editrice 2013, pp. 223-31.

Italia P., Raboni G., Che cos’è la filologia d’autore, Roma, Ca rocci 2010.

Italia P., Tomasi F., Filologia digitale, fra teoria, metodologia e tecnica, in «Ecdotica», 11 (2015), pp. 112-30.

Schillingburgh P.S., From Gutenberg to Google, Cambridge, Cambridge University Press 2006.

Serianni L., Le varianti fonomorfologiche dei Promessi Sposi 1840 nel quadro dell’italiano ottocentesco, in Id., Saggi di storia linguistica italiana, Napoli, Morano 1989, pp. 141-213.

Tanselle G.T., «Foreword to electronic textual editing» (2006), in Id., Portraits & Reviews, The Bibliographical Society of the University of Virginia, Charlotteville 2015, pp. 416-21.

Vitale M., La lingua di Alessandro Manzoni: giudizi della cri tica ottocentesca sulla prima e seconda edizione dei Promessi sposi e le tendenze della prassi correttoria manzoniana, Milano, Cisalpino 1992.

The research group

The research group

Sapienza University (Rome), Dept. of Studies Greek-Latin, Italian, Stage-Musical

Paola Italia (paola.italia@uniroma1.it) and Claudia Bonsi (claudia.bonsi@student.uniroma1.it)

Alma Mater (Bologna), Dept. of Computer Science and Engineering Fabio Vitali (fabio.vitali@unibo.it) and Angelo Diorio (angelo. diiorio@unibo.it).

This paper has been written in a collaborative way: the §§ 1, 2, 3 are due to Paola Italia, § 4 to Angelo Di Iorio e Fabio Vitali, § 5 to Claudia Bonsi.

Web sites

Web sites

Centro Nazionale di Studi Manzoniani www.casadelmanzoni.it

Edizioni Critiche Digitali www.ecdleopardi.altervista.org

Edizioni Genetiche Analitiche www.fabiovitali.it/filologia/#

Filologia 2.0 Edizioni WIKI http://www.filologiadautore.it/wiki/index.php?title=Pagina_principale

Notes

Notes

1 A. Di Iorio, P. Italia, F. Vitali, Variants and versioning between Textual Bibliography and Computer Science, Proceedings of the Third AIUCD Annual Conference on Humanities and Their Methods in the Digital Ecosystem, 2014 http://dl.acm.org/ citation.cfm?id=2802614

2 On the contrary, if we consider texts born in digital age (poems, novels, essays, and so on), written on the web and for the web, the matter is different, we need a new Philology for new texts, a Philology 2.0 (cfr. Italia 2013, pp. 223-25).

3 G.T. Tanselle, «Foreword to electronic textual editing» (2006), in Id., Portraits & Reviews, The Bibliographical Society of the University of Virginia, Charlotteville 2015, p. 418.

4 D. De Robertis, «Il Coro dei morti nello studio di Federico Ruysch», in D. De Robertis, Genesi, critica, edizione, Pisa, Annali della Scuola Normale di Pisa 1998.

5 P. Italia, F. Tomasi, Filologia digitale, fra teoria, metodologia e tecnica, in «Ecdotica», 11 (2015), p. 121 and see also Tomasi’s website of Vespasiano da Bisticci’s Letters (http://vespasianodabisticciletters.unibo.it/) which provides an infrastructure to enrich semantic knowledge of Letters’ expressive ability.

6 Even if is now available a mechanic recognition of handwriting which should facilitate the transcription of a text (cfr. https:// transkribus.eu/Transkribus/).

9 Laboratorio Manzoni: Commentare i Promessi Sposi, a.a. 2014-2015. (http://www.lettere.uniroma1.it/node/5601/6421)

10 For the principles of authorial philology see Isella, Le carte mescolate and, for a recent and effective systematisation of the matter, P. Italia, G. Raboni, Che cos’è la filologia d’autore, Roma, Carocci 2010.

11 The critical method called critica delle varianti was founded by Gianfranco Contini with his paper Come lavorava l’Ariosto. See G. Contini, Come lavorava l’Ariosto [1937], in Id., Esercizi di lettura sopra autori contemporanei con un’appendice su testi non contemporanei, Torino, Einaudi 1974.

12 L. Serianni, Le varianti fonomorfologiche dei Promessi Sposi 1840 nel quadro dell’italiano ottocentesco, in Id., Saggi di storia linguistica italiana, Napoli, Morano 1989, pp. 141-213, M. Vitale, La lingua di Alessandro Manzoni: giudizi della critica ottocentesca sulla prima e seconda edizione dei Promessi sposi e le tendenze della prassi correttoria manzoniana, Milano, Cisalpino 1992.

¬ top of page