« indietro

Giacomo Leopardi’s Zibaldone as a digital research platform:

a methodological proposal for its semantic reconstruction and discursive mediation

di Silvia Stoyanova

Trier, sms116@caa.columbia.edu

Abstract:

Giacomo Leopardi’s collection of fragmentary research notes known as the Zibaldone, has presented its author and scholars with challenges of semantic and discursive organization. The project of building a digital research platform for the Zibaldone aims to respond to these challenges and to facilitate scholarly research by implementing the affordances of XML and HTML technologies to allow the reconstruction of its semantic and bibliographic networks, the strategic retrieval of Leopardi’s own editorial annotations on the text, as well as the addition of user annotations.

I miei disegni letterari sono tanto più in numero, quanto è minore la facoltà che ho di metterli ad esecuzione; [...] I titoli soli delle opere che vorrei scrivere, pigliano più pagine; e per tutto ho materiali in gran copia, parte in capo, e parte gittate in carte così alla peggio.

G. Leopardi, letter to P. Colletta, January 16, 1829

I. Leopardi’s research note collection and its discursive challenges

Giacomo Leopardi’s Zibaldone belongs to a strand of ‘failed’ modern epics which has yet to find an ef fective critical and editorial methodology – the note books of fragmentary reflections of prominent intellectuals, whose research projects never attained narrative form [1]. This kind of unachieved text is generated by authorial intentionality whose ethical motivation, encyclopedic ambition and epistemological methodology in composing scholarly narratives present insurmountable discursive challenges, especially in the paper medium where the semantic coherence of the fragments is scattered over vast material space. Leopardi’s lamented shortcoming in converting his notable potential as scholar and author into opus is concretely embodied in the voluminous fragmented corpus of his Zibaldone di pensieri.

The Zibaldone manuscript consists of six notebooks of 4526 numbered pages and ca. 3678 fragmented reflections delimited by their date of composition; it is marked with thousands of underlined words, marginal, interlinear and inline additions. In the course of fifteen years, the fragments engendered each other, as evidenced by the numerous cross-references between them (some composed explicitly as a continuation of the referenced passage) and by the frequent implicit references to previously discussed subjects. The formal fragmentariness of the text reflects its thematically, linguistically and stylistically heterogeneous contents: quotations and bibliographic references; commentaries on referenced works; reflections on a vast variety of topics – from linguistics and literary criticism to anthropology and metaphysics; aphorisms; memoir sketches; lyricisms. In a letter to his publisher Antonio Stella from September 13, 1826, while discussing one of his publication projects based on the Zibaldone – a philosophical dictionary after Voltaire’s, Leopardi comments on the difficulty of revising the gathered material for publication because of its minimal style and formal organization which make it barely intelligible to another reader: «Quanto al Dizionario filosofico, le scrissi che io aveva pronti i materiali, com’è vero; ma lo stile ch’è la cosa più faticosa, ci manca affatto, giacché sono gittati sulla carta con parole e frasi appena intelleggibili, se non a me solo. E di più sono sparsi in più migliaia di pagine, contenenti i miei pensieri; e per poterne estrarre quelli che appartenessero a un dato articolo, bisognerebbe che io rileggessi tutte quelle migliaia di pagine, segnassi i pensieri che farebbero al caso, li di sponessi, gli ordinassi ecc.».

The manuscript material presents the mediation challenges of manifold fragmentariness: of its dispersal over a vast textual terrain; of its compound syntax cluttered by relative clauses, often added between the lines and in the margins; and of its phenomenological discourse, lacking the style of strong authorial intentionality and sutured instead by a grid of cross references. The Zibaldone’s heterogeneity, however, is an organically interconnected aggregate generated by the author’s continual attentiveness to the observed phenomena over an extended period of time, which accounts for their high potential for association and which requires him to work through the entire manuscript (amounting to 4200 pages at the time of writing the above letter) in order to extract the material pertinent to any given subject. Once Stella commissioned the philosophical dictionary, Leopardi undertook the arduous task of editing his note collection in the summer of 1827 by distributing the material thematically with the help of index cards, which were subsequently compiled into an alphabetical index listing ca. 1000 headings and sub-headings. Of these, 169 cross-reference other index themes according to relations of synonymy, antonymy, hypernymy, and meronymy: for example «Culto» has a reference to the heading «Religione»; «Dialetti italiani» to «Toscano (volgare)»; «In sensibilità» to «Compassione» and «Beneficenza», etc. Besides the overarching designs for a philosophical dictionary and an [2], Leopardi had more nar rowly defined writing projects for utilizing his research material. A few of the 1827 Index headings list a great er number of passages than the average dozen, suggesting titles of works, such as «Civiltà. Incivilmento», «Continuativi latini», «Greci», «Romanticismo», «Teoria del piacere», etc. Another series of treatises can be gathered from the headings of the so-called «PNR Index», which consists of eight general themes group ing 2264 passages, among which «Teorica delle arti, lettere» in two parts, «Trattato delle passioni, qualità umane», «Manuale di filosofia pratica», etc. [3].

Leopardi’s meticulous textual analysis in assigning ca. 11,000 Zibaldone segments to multiple thematic categories with various degrees of semantic specificity and in establishing cross-references between fragments with different degrees of target specificity (ranging from lines in a paragraph or a marginal comment on a page to a range of pages) and between index themes (with a range of semantic values), probes deeply into the individual semantic associations that compose his note collection. However, the complex dimensionality of their intersecting semantic fields is lost in the arbitrary alphabetical order of the headings, which Leopardi had adopted from his 18th-century models, Voltaire’s Dictionnaire Philosophique, and Diderot and D’Alembert’s Encyclopédie ou Dictionnaire raisonné des sciences, des arts et des métiers. The proto-hypertextual expedient of cross-references, to which both Leopardi and Diderot resorted in their endeavor to capture the relativistic structure of their texts, is suggestive but very limited in its organizational and discursive capacity. Whether and how Leopardi attempted to use his analysis of the Zibaldone for composing his projected works is a matter of speculation, but the scholarly engagement with the text’s encyclopedic ambition and phenomenological discourse similarly confronts significant mediation challenges, despite the aid of sophisticated print editions and of digital remediations, such as the CD-ROM or the wiki project, which enhance the text’s analytical methods but do not activate its relational features beyond basic hyperlinking [4]. Hyperlinks connect the sequence of re lated passages for more immediate perusal, but they still move in linear space to the extent that they do not chart that sequence in a meaningful way [5]. The close textual analysis performed by Leopardi and his editors, who have expanded significantly on the authorial thematic index and cross-references [6], is suggestive in its interconnected hypertextuality, however fails to analyze the semantics of the resulting networks of hy perlinked relationships. One of the biggest challenges of this digital project, therefore, is to formulate a taxonomy to describe the semantic relationships between textual fragments, and thereby to transform the Zibaldone’s virtual hypertextual organization into a small scale prototype of a semantic web, which demands a suitable platform for its navigation.

If we attempt to demarcate the relational complexity of the semantic field of broad subjects (such as «style» and «nature») or of recurrent concepts which escaped Leopardi’s editorial attention and were not indexed (such as «cura») by extracting the passages where the term appears and then follow the threads of their references, parts of the Zibaldone would be replicated (often several times) from the perspective of the chosen focal point and their order would present considerable difficulties or prove impossible to unfold in the two-dimensional space of the codex or the digital page of a Word file. Surveying the entire text from the standpoint of any given subject of its encyclopedic scope would be a valuable exploratory method if it could be automatically generated on the basis of cross-references and index themes in the form of a thematic map, which indeed is how Diderot envisioned the representation of semantic order in the Encyclopédie [7]. The links between cross-referenced passages sometimes align them into narrative threads or cluster them into networks, demanding graphical rendition. The links between passages grouped by the thematic indexes further multiply and specify the semantics of interrelations in the Zibaldone, making another claim for implementing the multidimensional discursive potential of the digital medium.

The project of reconstructing the semantic structure of the Zibaldone as a digital platform aims to facilitate scholarly research by enabling the strategic retrieval of Leopardi’s own editorial work and including that of his scholars, and by adding tools and con tents for its further analysis enabled by XML and HTML technologies. The research platform incorporates the intertextual network of the text’s bibliographic references, a biographical database of the normalized names of persons mentioned in the text, and modules for sharing user annotations. Opening the platform to a community of editors, which collective knowledge building privileges process over end result (Siemens et al., 2012), is particularly relevant to the Zibaldone’s processual, modular and interconnected textuality, as these demand significant reader interaction and offer multiple semantic frameworks that could be explored. Scholars can add the results of their own research to the editorial features of the platform or contribute to defining or expanding the thematic indexes, establishing or qualifying additional cross-references between passages and between individual themes in the indexes, thus creating cumulative layers of interpretation which can be consulted by future users, as well as analyzed statistically.

Another very experimental stage of the project is to create a platform to support the process of formalizing the fragmentary records of research activity into multi layered narrative configurations by producing graphical representations of the text’s relational structures. For this agenda of finding the proper discursive mediation for fragmentary research material that resists streamlining into traditional stylistic forms of scholarship, it is useful to recuperate the idea of scholarly hypertext, which, despite being the originary context of hypertext technology, has found scant scholarly implementation. Its major practitioner, David Kolb, had argued already in 1997 for constructing enhanced composition, presentation and publication platforms for argumentative writing by exploiting the semantic relatedness of textual units in a spatial environment with graphical display: «There should be advantages to presenting ideas and assertions in regions that are multiply explodable landscapes located in complex relations to others. Imagine even as small a text as this present essay presented in several regions with multiple links on different levels of detail instead of the paragraphs plus digressive foot notes» [8]. However, as Kolb notes a decade later, there seem to be few scholarly contents with complex style that intrinsically demand the discursive modes of spatial argumentation [9]. On the other hand, as Johanna Drucker has been contending in her call for a critical understanding of the graphical methods for analyzing, organizing and producing knowledge, it is our digital screens that continue to imitate print and do not foster the diagrammatical imagination that we already naturally employ in our handwriting: «Diagrammatic techniques used in note taking express associative thinking about ideas and arguments. […] But the potential of the electronic environment to create those multiplicities of argument structure that are possible within the digital spaces of an n-dimensional screen has not yet been activated» [10]. This project’s experimental agenda is based on the hypothesis that the research notebook genre’s intrinsic demand for relational discursive mediation could find a working platform in the «constellationary, distributed, multi-faceted modes» for producing scholarship envisioned by Drucker [11].

II. Zibaldone digital research platform: features and functionalities

II. Zibaldone digital research platform: features and functionalities

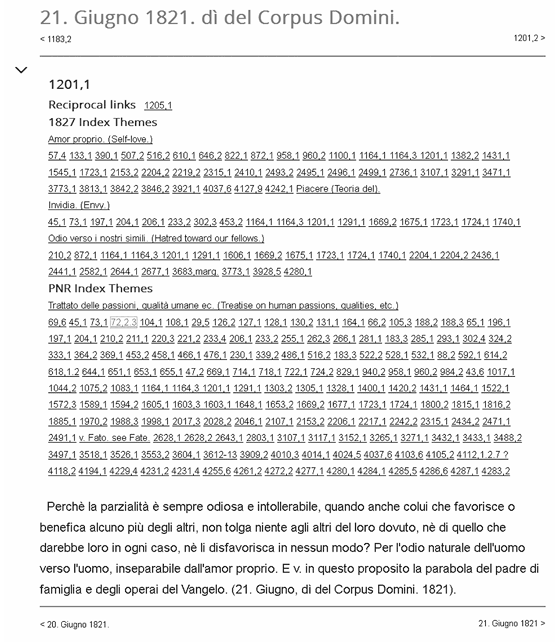

The digital Zibaldone platform’s current stage of development is based on a TEI encoding of the text, host ed in eXist XML database with Drupal CMS and can be consulted at http://zibaldone.princeton.edu [12]. Its main features address the representation and navigation of the stratified composition of the text, its hypertextual structure, and its thematic relationality, as established by its author and editors. The platform settings allow to distinguish these layers and to choose which ones to include in using the interface. Manuscript features that can be evidenced on demand include underlining, markers for quotes, marginal, interlinear and inline comments; editorial additions include paragraph numbers (the manuscript only marks pages, but the majority of references in the indexes are directed to paragraphs), date suggestions, link suggestions for Leopardi’s implicit references, underlining for emphasis, explanatory notes. Many encoded elements, such as variations and dating of the ink used in the manuscript, individual responsibility for editorial additions, qualifications of the semantics of link references, bibliographical references, place names, person names and their attributes, still need to be implemented into the site interface. The thematic associations recorded in the indexes could be explored with computational methods for analyzing semantic relatedness which could be compared to the author’s manual analysis. Statistical charts and graphic visualizations of the relational web of encoded elements are still rudimentary. The user participation modules are in the process of being designed. However, the platform is already operational in assisting the strategic navigation and mining of the text by activating its cross-references, linking the thematic headings of the indexes, and harvesting Leopardi’s analysis of its semantic patterns by providing an informational window, automatic generation and export of thematic relationships from the indexes, and their visualization as graphs.

Informational window: cross-references, thematic threads and networks

Informational window: cross-references, thematic threads and networks

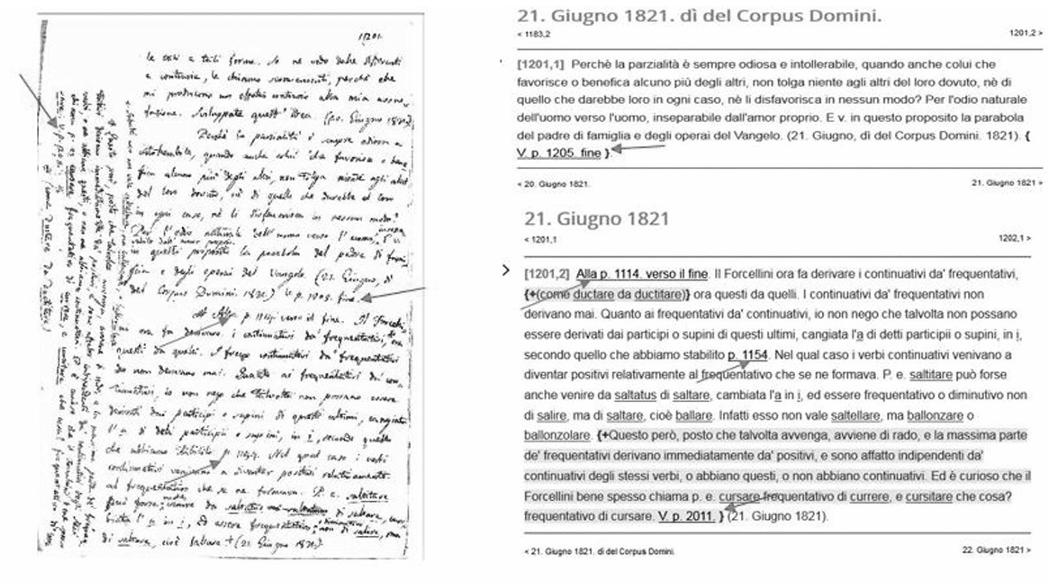

The informational window is a central feature of the platform’s synoptic functionality. It gives an overview of each paragraph’s immediate semantic field of relations, first on the basis of its cross-references followed to the first degree, distinguishing three types of references: reciprocal, outgoing and incoming, and second, on the basis of the index themes. If the reader were to follow the authorial indication of references in the course of reading the text, information about any incoming but not reciprocal references would likely be missed given the length of the text, unless they are in close proximity to the referenced passage. As can be seen from the manuscript facsimile of the two paragraphs (and date divisions) on p.1201 and its html rendering (Fig. 1) [13], some references appear as marginal or inline annotations and refer to subsequently written passages (p.1205 and p.2011, evidenced by the red arrows), suggesting their addition during re-reading on other occasions. Others are made in the course of writing, such as the reference to p.1154 written some 10 days earlier (green arrow). Yet others indicate the explicit continuation of a previous thought, such as the reference to p. 1114 at the very beginning of par. 1201,2 (blue arrow). These have been given the attribute of “subordinate” in the TEI encoding, to indicate that their relatedness is closer in comparison to references established in parallel to the given pas sage, in an experiment to give semantic value to the link references.

Fig. 1. Facsimile and platform rendering of p.1201 of the Zibaldone.

Fig. 1. Facsimile and platform rendering of p.1201 of the Zibaldone.

As already mentioned, there is another category of link relatedness, which is based on the degree of authorial intentionality, namely the implicit references, many of which have been suggested by editors of print editions of the Zibaldone (Pacella; Caesar and D’Intino). Based on content, some references are strictly bibliographical, pointing to where a work was cited previously, and their semantics could also be evaluated under a separate category. Furthermore, the target of references differs in its segmentation, suggesting another possible approach to categorize the link references within the manuscript.

The informational window does not yet have the desirable function of harvesting further degrees of references, which could also implement an ontology of their relationships, but it provides a basic idea of the thematic associations of a given paragraph by also listing any index headings to which it is assigned, with the option to view and link to the other passages under the same index headings. Whereas the informational window now simply gathers the encoded information in a list, it could be followed by computational analysis and graphical representation of the intersections between the thematic threads and net works of explicit and implicit cross-references and the constellation of related passages listed under the same index theme. Computational support becomes indispensable to the extent that the user would like to pursue all the ramifications and contexts of how a logical argument unfolds, which is particularly useful given Leopardi’s tendency to continuously relativize statements (sometimes to the point of dialectical reversal) and to transfer terminology from one context to another, where it acquires more, often surprising connotations, as in the analogical methodology of «encyclopedistics» practiced by Novalis in his own research Notes for a romantic encyclopedia.

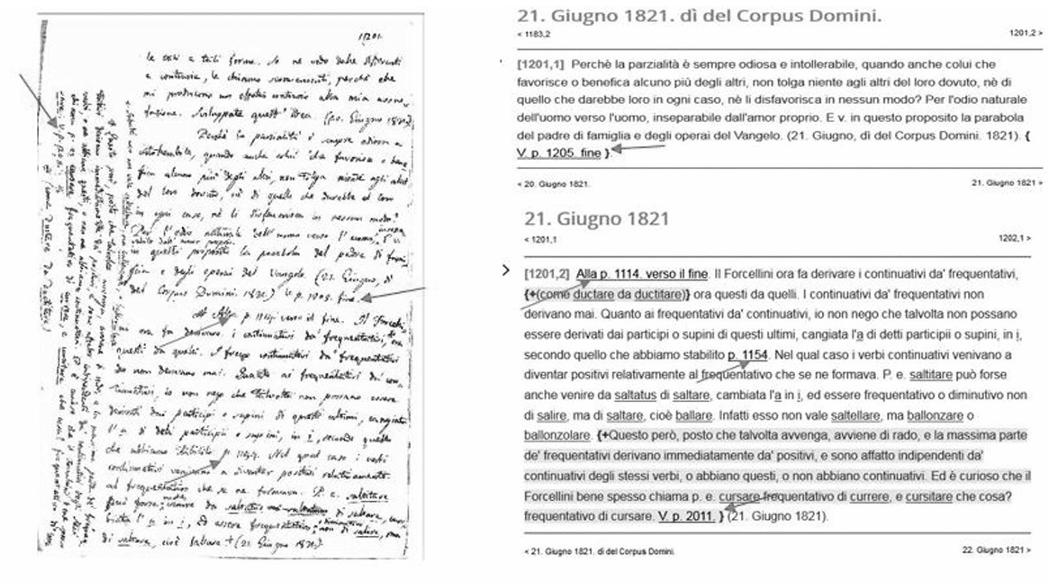

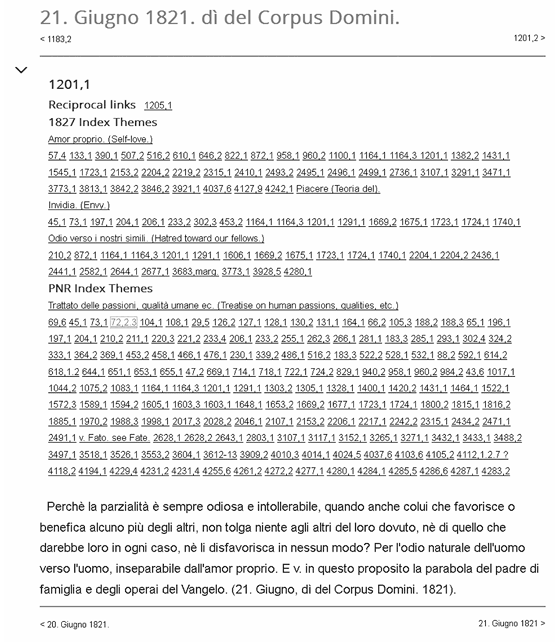

Reconstructing the thematic field of a passage by navigating its references is feasible also on paper to the extent that it forms a linear or short thread, but it is not always possible to capture its scope, while its references become impossible to follow either in print or as hyperlinks when they form networks with multiple and overlapping sequences, as the two paragraphs on p.1201 exemplify (Fig. 2):

Fig. 2. On the left, thematic thread of par.1201,1 based on all references with corresponding index themes. To the right, thematic network sketch of par. 1201,2 based on references to the third degree.

Fig. 2. On the left, thematic thread of par.1201,1 based on all references with corresponding index themes. To the right, thematic network sketch of par. 1201,2 based on references to the third degree.

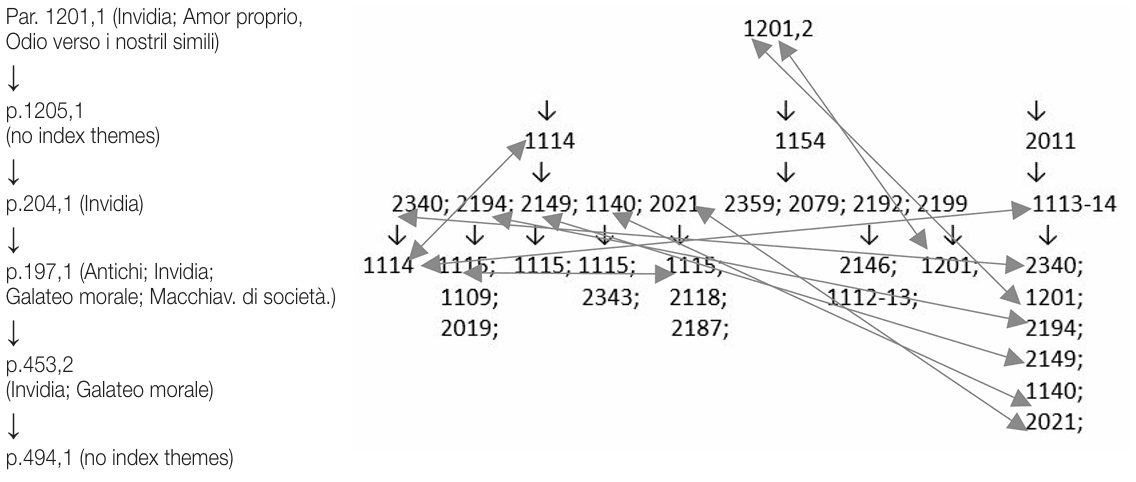

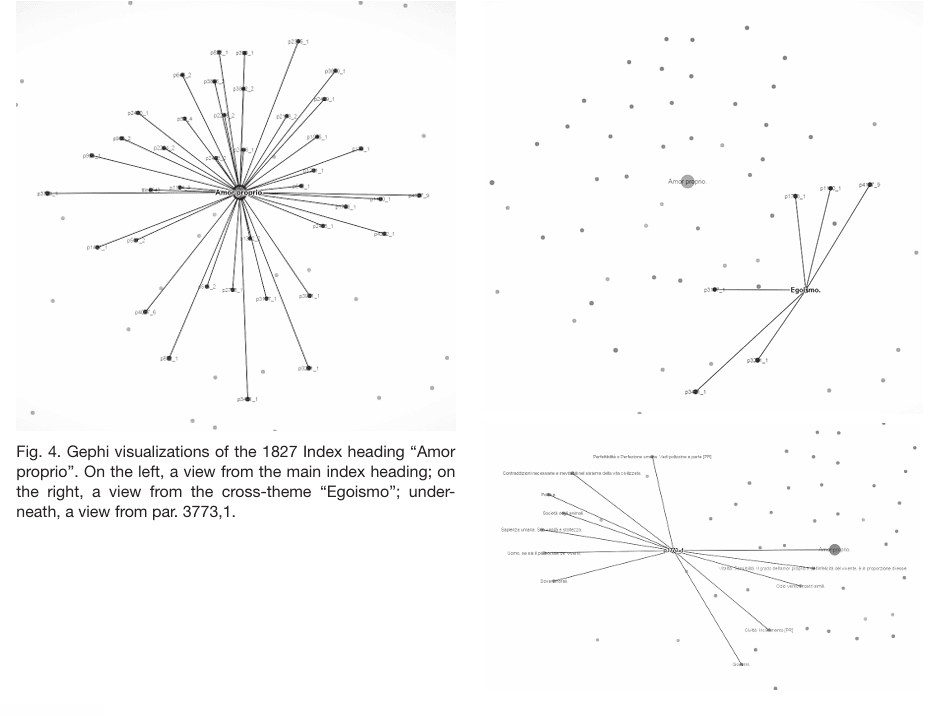

Par. 1201,1 has a single reference to par. 1205,1, which has no further references, but if the reader is using a print edition that gives suggestions for the implicit references, this thread will continue to p. 204 (implicit) and proceed to p.197, p. 453 and end at p. 494. The recurrent index heading of all referenced (and indexed) paragraphs thread is «invidia» and it is also one of three headings from the 1827 Index associated with par. 1201,1, which information, besides in this platform feature (Fig. 3), can be found only in the tabulations of Peruzzi’s facsimile edition, since Leopardi’s index is alphabetical. The thread of cross references thus captures only one of the three index themes, whereas the other two thematic groups of passages appear unrelated on the basis of link references in the manuscript. This comparison between the narrower semantic field of the references and of the more thorough one of the indexes, which can be tested computationally on a large scale for the entire text, suggests a possible distinction in the significance of the assigned themes. «Invidia» appears to be more pertinent to this passage, while its relatedness to pas sages belonging to the other two themes seems to have escaped altogether Leopardi’s attention in the course of writing. Similarly, the referenced passages in the thread that are also listed under «invidia» appear to have a closer relation to par. 1201,1 than the additional 13 ones listed under the same index heading. On the other hand, the relation to par. 494,1, which is the last link of the manually generated thematic thread, is missed by the informational window altogether, because it only lists first degrees of references and this particular paragraph was not indexed by Leopardi. Therefore, a desirable development of this feature would be to in clude all of the degrees of references, which will likely require graphical representation. Any associated headings from the PNR Index, which is the most general level of thematic relatedness encoded by Leopardi, are also provided by the window.

Fig. 3. Informational window, par. 1201,1.

Fig. 3. Informational window, par. 1201,1.

In the case of the second paragraph on p.1201 (as with many fragments on linguistics), the associations based on the references diverge in multiple directions, showing even more clearly the need for graphical or multi-dimensional support of their analysis (Fig. 2). There are three immediately outgoing links and if we begin to follow subsequent degrees of references, the narrative thread quickly grows centrifugally, sometimes looping on itself, while specific arguments gradually diffuse into the general category of Latin frequentative and diminutive verbs. This example shows the utility of listing incoming references in the informational window: the incoming reference to par. 1201,2 would most likely be missed from its location, since the link from par. 2199,1 arrives almost a thousand pages later. The general objective of the research platform is to extract all of the semantic information pertinent to a particular fragment, to get an overview of the thematic content of any fragment in the context of its larger semantic fields, and to capture and align the comprehensive development of the text’s interconnected arguments, which still requires a lot of computational processing.

Thematic extraction of contents and graphical display

Thematic extraction of contents and graphical display

While the platform still needs an interface that more effectively combines and mines the information from the cross-references with that of the indexes, the indexes can be further exploited for extracting the textual contents of all paragraphs belonging to an index heading which could be exported to a Word file. The list of paragraphs contains the additional index themes assigned to each paragraph, as in the informational window. A desirable feature would be to combine all of the additional themes from the individual paragraphs and list them under the main index heading as a chart according to their frequency. This is even more pertinent to the so-called PNR index, which lists a much greater number of paragraphs under a single heading. A similar interface is used for search results: the list of paragraphs containing the keyword can be selected for export in Word and each paragraph is listed along with its index themes. It is desirable for the search to harvest not only the keyword passages but also those referenced in them and provide a graphical display of the results.

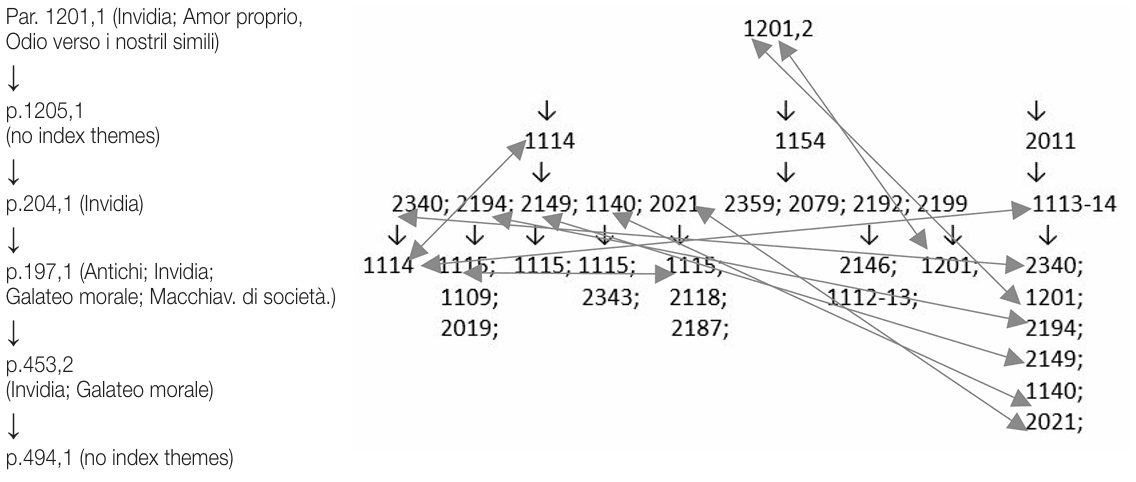

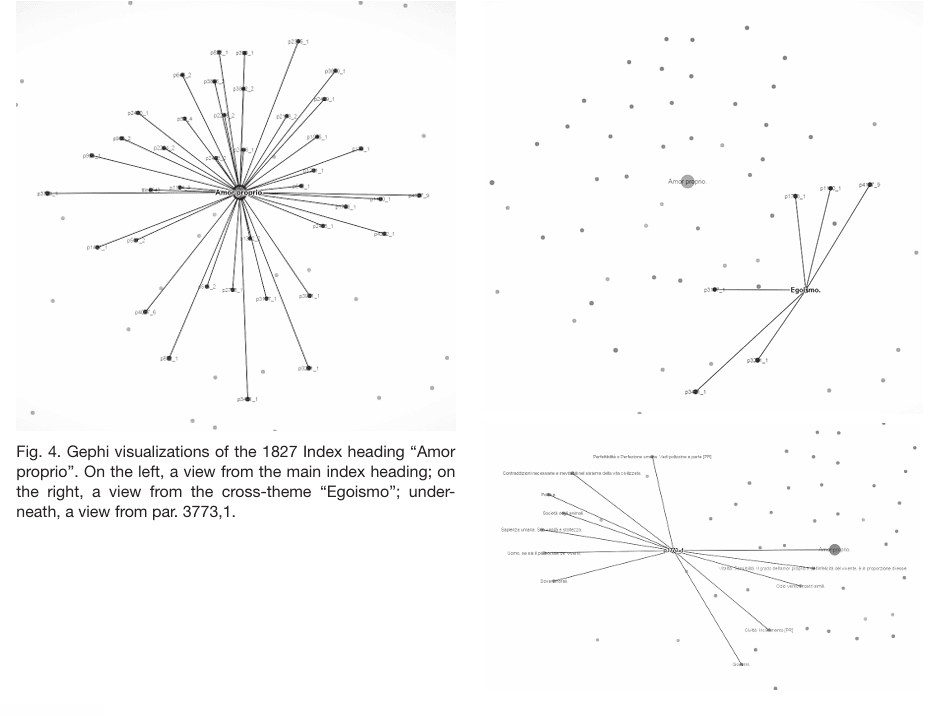

Basic Gephi graphs can be dynamically generated on the platform site for each of the index themes. The graph allows views from an index-heading node, highlighting its paragraphs; from a cross-theme node, highlighting its paragraphs within the central node’s semantic field; and from a paragraph node, highlight ing its related index themes (Fig. 4). The graph’s main imitations are that only one degree of references can be followed and its display modes can be viewed one at a time, whereas it would be useful to freeze previously explored paths, as one proceeds to browse the larger area. The graphical representation of the index networks has the potential to display overlapping the matic areas with precise definition and scale, but for now, their utility is limited to giving an impression of the magnitude of thematic interconnectedness at work in the Zibaldone.

Fig. 4. Gephi visualizations of the 1827 Index heading “Amor proprio”. On the left, a view from the main index heading; on the right, a view from the cross-theme “Egoismo”; under neath, a view from par. 3773,1.

Fig. 4. Gephi visualizations of the 1827 Index heading “Amor proprio”. On the left, a view from the main index heading; on the right, a view from the cross-theme “Egoismo”; under neath, a view from par. 3773,1.

Other content elements could also benefit from visual representation. The percentage of quotes and bibliographical references of the text can be presented as a histogram, to which additional content elements could be added, such as a thematic map of the areas with high proportion of quotes and bibliographic references for a quick overview of the Zibaldone’s intertextuality, a map which could also include time period, genre, author, country, etc. Another map can be generated of the persons mentioned in the text, along with their attributes of type, time period, provenance, etc., against the background of a thematic histogram, etc.

The mediation effected by the (relatively) distant reading of graphs, maps, and charts not only facili tates the explorative analysis of the text but could be instrumental in reproducing and capturing the figurative process of thought which engenders the kind of romantic fragment writing that defies expository narrative [14], as Leopardi (among other practitioners of the genre) describes it:

Quindi è che scoprendo in un sol tratto molte più cose ch’egli non è usato di scorgere a un tempo, e d’un sol colpo d’occhio discernendo e mirando una moltitudine di oggetti, ben da lui veduti più volte ciascuno, ma non mai tutti insieme (se non in altre simili congiunture), egli è in grado di scorger con essi i loro rapporti scambievoli, e per la novità di quella moltitudine di oggetti tutti insieme rappresentanti segli, egli è attirato e a considerare, benchè rapida mente, i detti oggetti meglio che per l’innanzi non avea fatto, e ch’egli non suole; e a voler guardare e notare i detti rapporti. (Zibaldone, pp. 3269-70).

The synoptic vision of a great number of interrelated phenomena, which is sometimes granted to the thinker after having analyzed them closely one at a time, reveals them in a new perspective which compels to «want to look at and to note these relationships», however briefly [15]. A machine reading, based on the encoding of close analysis, could extract these relationships from the continuum of their phenomenological description, bring them together, render them visually and arrest that vision, so that they can be revisited from new angles, lending them greater discursive power. The mediation of such relativistic perspective into scholarship demands the discursive mediation of diagrams, charts, maps, graphical disposition and linking of textual elements, as well as a community of editors.

A call for participation

A call for participation

This project has been propelled for the most part by the voluntary effort of two scholars with limited institutional support and expertise in respect to its potential for development, however the call for participation in this text is also motivated by factors intrinsic to its genre and to the project’s objective to offer a platform for its discursive mediation. The fragmentary records of phenomenological inquiry, where «one does not write primarily for being understood; one writes for having understood being» [16], distribute authorial intentional ity to its readers and summon the romantic notion of collaborative and performative criticism which needs «an interface that is meant to expose and support the activity of interpretation, rather than to display finished forms» [17].

Bibliography

Bibliography

Axelrod C.D., Toward an Appreciation of Simmel’s Fragmen tary Style, in «The Sociological Quarterly» 18, 2 (1977), pp. 185 96.

Caccipuoti F., Edizione tematica dello Zibaldone di pensieri stabilita sugli Indici leopardiani, Roma, Donzelli 1997.

Caccipuoti F., «La scrittura dello Zibaldone tra sistema filosofico ed opera aperta», in Lo Zibaldone cento anni dopo: compo sizione, edizioni, temi: atti del X Convegno internazionale di studi leopardiani: Recanati-Portorecanati, 14-19 settembre 1998, Ed. Franco Foschi et al., Firenze, Olschki 2001, pp. 249-56.

Caccipuoti F., Dentro lo Zibaldone: il tempo circolare della scrittura di Leopardi, Roma, Donzelli 2010.

Caccipuoti F., Zibaldone di pensieri: nuova edizione tematica condotta sugli indici leopardiani, Roma, Donzelli 2014.

Drucker J., Humanities Approaches to Interface Theory, in «Culture Machine» 12 (2011), pp. 1-20.

Drucker J., Diagrammatic Writing, in «New Formations» 78 (Summer 2013), pp. 83-101.

Drucker J., Graphesis: Visual Forms of Knowledge Production, Cambridge, Harvard University Press 2014.

Kolb D., «Scholarly Hypertext: Self-Represented Complexity», in HT ’97 Proceedings of the eighth ACM conference on Hypertext 1997, pp. 29-37.

Kolb D., Association and Argument: Hypertext in and around the Writing Process, in «The New Review of Hypermedia and Multimedia», 11, 1 (2005), pp. 7-26.

Kolb D., «The Revenge of the Page», in HT ’08 Proceedings of the nineteenth ACM conference on Hypertext and hypermedia 2008, pp. 89-96.

Leopardi G., Zibaldone di pensieri, Ed. G. Pacella, Milano, Garzanti 1991.

Leopardi G., Zibaldone di pensieri, Eds. F. Ceragioli, M. Balle rini, Milano: Zanichelli 2009. CD-ROM edition.

Leopardi G., Epistolario, in Tutte le poesie, tutte le prose e lo Zibaldone, Eds. L. Felici, E. Trevi., Rome, Newton Compton 2013.

McDonald C., The Utopia of the Text in Diderot’s ‘Encyclopédie’, in «The Eighteenth Century» 21, 2 (1980), pp. 128-44.

Nancy J.-L., Lacoue-Labarthe P., The Literary Absolute, Albany, SUNY Press 1988.

Siemens, R. et al. “Toward Modeling the Social Edition”, Digital Scholarship in the Humanities 27, 4 (2012), pp. 445-61.

Stoyanova S., Johnston B., «Remediating Giacomo Leopardi’s Zibaldone: Hypertextual Semantic Networks in the Scholarly Archive», Proceedings of AIUCD ’14. New York: ACM 2015.

Van Manen M. Writing Qualitatively, or the Demands of Writing, in «Qualitative Health Research» 16, 5 (2006), pp. 713-22.

Notes

Notes

1 Some prominent examples of these potential texts are Lichtenberg’s Sudelbücher, Pascal’s Pensées, Joubert’s Carnets, Novalis’ Allgemeine Brouillon, Coleridge’s Notebooks, Valéry’s Cahiers, Benjamin’s Passagenwerk, Wittgenstein’s Culture and Value, Philosophical Investigations, etc. Genetic criticism’s attention to the analysis of the creative process recuperates the achieved text’s potentiality beyond the form constructed by the selection process of authorial intentionality; however, its methodology does not adequately address the processual textuality of intellectual notebooks, because these are scholarly texts in which the selection process becomes so complex as to never produce narrative form.

2 Leopardi discusses the Encyclopedia project with Stella in a series of letters from July 13 1827 (two days after starting to index the Zibaldone), August 23, 1827, November 23, 1827, and August 19, 1828, in which he repeatedly mentions the inadequate style of his material and the time its editing would demand.

3 F. Cacciapuoti, who has convincingly argued for the systematic tension and projecting intentionality at work in the Zibaldone (2001; 2010), has offered two thematic editions of the text (1997; 2014) according to the lists of passages under the «PNR Index».

4 Peruzzi’s facsimile edition (1989-1994) provides two computational tabulations based on the indexes: one is chronological and lists all the themes assigned to each paragraph; the other is alphabetical by theme and lists all cross-themes relevant to each paragraph under a certain theme. When the intricate interlacing of the Zibaldone is thus spun out over hundreds of pages, the mediation of its fragmentariness into higher orders of semantic organization becomes quite daunting. In the digital realm, the CD-ROM edition of Ceragioli and Ballerini provides images of the facsimile, records all the variations Leopardi made to the text, thus offering an authoritative transcription, determines the location of unattached marginalia, offers a word, page and name search function, all of which are very useful analytical tools; however, it gives a static representation of the text and does not link the manuscript to the indexes. The wiki project

(http://it.wikisource.org/wiki/Progetto:Letteratura/Zibaldone) enables the navigation of the cross-references, but offers no means to explore the seman tics of their relationships or to exploit those established by the indexes.

5 The application of hyperlinking in scholarship has not advan ced much further in its semantic potential than its proto-fun ction in V. Bush’s Memex, as David Kolb explains: «An association on a trail does not make a specific claim except that a connection exists. If the links on the trail were labeled with different types, then the trail could begin to assert specific kinds and directions of connection, but a series of such connections would still not have the intricate interrelations and subordinations found in the propositions of an argument» (2005, p. 8).

6 Especially Caesar and D’Intino (2013), Damiani (1997), Pacella (1991), Peruzzi (1989-1994).

7 C. McDonald, The Utopia of the Text in Diderot’s ‘Encyclopédie’, in «The Eighteenth Century» 21, 2 (1980), pp. 131-4; p. 143.

8 D. Kolb, «Scholarly Hypertext: Self-Represented Complexi ty», in HT ’97 Proceedings of the eighth ACM conference on Hypertext, 1997, p. 35.

9 Id., «The Revenge of the Page», in HT ’08 Proceedings of the nineteenth ACM conference on Hypertext and hypermedia, 2008, p. 93.

10J. Drucker, Diagrammatic Writing, in «New Formations» 78 (Summer 2013), p. 101.

11Ead., Humanities Approaches to Interface Theory, in «Culture Machine» 12 (2011), p. 2.

12For a detailed discussion of the project’s methodologies of remediating and encoding the Zibaldone, see Silvia Stoyanova and Ben Johnston (2015).

13The image of the facsimile is a screenshot from the CD-ROM edition by Ceragioli and Ballerini (2009).

14As Jean-Luc Nancy and Philippe Lacoue-Labarthe write in their classical work on the theory of literature in German Romanticism, the romantic texts’ ineptitude to practice systematic exposition «bears witness to the fundamental impossibility of such an exposition, whenever an order of principles according to which the order of reasons unfolds is lacking. Such an order is lacking here, but rather by excess than by default» (1988, p. 44). The multitude of simultaneously perceived relations prevents narrative order, and in the absence of spatial representation thought takes the form of fragments with high signifying agency.

15Leopardi’s epistemological phenomenon of ‘colpo d’occhio’ resembles the formative process of Georg Simmel’s fragmentary style, as described by Wolff in his introduction to The Sociology of Georg Simmel (1950, p. xix): «Simmel often appe ars as though in the midst of writing he were overwhelmed by an idea, by an avalanche of ideas, and as if he incorporated them without interrupting himself, digesting and assimilating only to the extent granted him by the onrush». Cited in David C. Axelrod (1977, p. 193).

16M. Van Manen, Writing Qualitatively, or the Demands ofWri ting, in «Qualitative Health Research» 16, 5 (2006), p. 721.

17J. Drucker, Graphesis: Visual Forms of Knowledge Production, Cambridge, Harvard University Press 2014, p. 179.

3 F. Cacciapuoti, who has convincingly argued for the systematic tension and projecting intentionality at work in the Zibaldone (2001; 2010), has offered two thematic editions of the text (1997; 2014) according to the lists of passages under the «PNR Index».

4 Peruzzi’s facsimile edition (1989-1994) provides two computational tabulations based on the indexes: one is chronological and lists all the themes assigned to each paragraph; the other is alphabetical by theme and lists all cross-themes relevant to each paragraph under a certain theme. When the intricate interlacing of the Zibaldone is thus spun out over hundreds of pages, the mediation of its fragmentariness into higher orders of semantic organization becomes quite daunting. In the digital realm, the CD-ROM edition of Ceragioli and Ballerini provides images of the facsimile, records all the variations Leopardi made to the text, thus offering an authoritative transcription, determines the location of unattached marginalia, offers a word, page and name search function, all of which are very useful analytical tools; however, it gives a static representation of the text and does not link the manuscript to the indexes. The wiki project

(http://it.wikisource.org/wiki/Progetto:Letteratura/Zibaldone) enables the navigation of the cross-references, but offers no means to explore the seman tics of their relationships or to exploit those established by the indexes.

5 The application of hyperlinking in scholarship has not advan ced much further in its semantic potential than its proto-fun ction in V. Bush’s Memex, as David Kolb explains: «An association on a trail does not make a specific claim except that a connection exists. If the links on the trail were labeled with different types, then the trail could begin to assert specific kinds and directions of connection, but a series of such connections would still not have the intricate interrelations and subordinations found in the propositions of an argument» (2005, p. 8).

6 Especially Caesar and D’Intino (2013), Damiani (1997), Pacella (1991), Peruzzi (1989-1994).

7 C. McDonald, The Utopia of the Text in Diderot’s ‘Encyclopédie’, in «The Eighteenth Century» 21, 2 (1980), pp. 131-4; p. 143.

8 D. Kolb, «Scholarly Hypertext: Self-Represented Complexi ty», in HT ’97 Proceedings of the eighth ACM conference on Hypertext, 1997, p. 35.

9 Id., «The Revenge of the Page», in HT ’08 Proceedings of the nineteenth ACM conference on Hypertext and hypermedia, 2008, p. 93.

10J. Drucker, Diagrammatic Writing, in «New Formations» 78 (Summer 2013), p. 101.

11Ead., Humanities Approaches to Interface Theory, in «Culture Machine» 12 (2011), p. 2.

12For a detailed discussion of the project’s methodologies of remediating and encoding the Zibaldone, see Silvia Stoyanova and Ben Johnston (2015).

13The image of the facsimile is a screenshot from the CD-ROM edition by Ceragioli and Ballerini (2009).

14As Jean-Luc Nancy and Philippe Lacoue-Labarthe write in their classical work on the theory of literature in German Romanticism, the romantic texts’ ineptitude to practice systematic exposition «bears witness to the fundamental impossibility of such an exposition, whenever an order of principles according to which the order of reasons unfolds is lacking. Such an order is lacking here, but rather by excess than by default» (1988, p. 44). The multitude of simultaneously perceived relations prevents narrative order, and in the absence of spatial representation thought takes the form of fragments with high signifying agency.

15Leopardi’s epistemological phenomenon of ‘colpo d’occhio’ resembles the formative process of Georg Simmel’s fragmentary style, as described by Wolff in his introduction to The Sociology of Georg Simmel (1950, p. xix): «Simmel often appe ars as though in the midst of writing he were overwhelmed by an idea, by an avalanche of ideas, and as if he incorporated them without interrupting himself, digesting and assimilating only to the extent granted him by the onrush». Cited in David C. Axelrod (1977, p. 193).

16M. Van Manen, Writing Qualitatively, or the Demands ofWri ting, in «Qualitative Health Research» 16, 5 (2006), p. 721.

17J. Drucker, Graphesis: Visual Forms of Knowledge Production, Cambridge, Harvard University Press 2014, p. 179.

¬ top of page