« indietro

Certosa di Pontignano, 12th June 2015

The Mechanic Reader. Instead of a Preface

di Francesco Stella

Università di Siena,

francesco.stella@unisi.it

Abstract:

Introduction to the proceedings of the Siena 2015 conference about Digital Methods and Literary Criticism, presenting the initiative within a history of the ‘digital philology’ research projects at the University of Siena and highlighting the impact of the new insights among the professionals of literary studies as well as the fluctuations of criticism against the quantitative methods, frequently swinging from apparent interest (more in the technological tools than in the theoretical methods) and awkward pedantry about its unavoidable imperfections, rarely offering alternative trials or advice for possible improvements. And yet the quantitative processing of texts proves to be one of the most promising innovations in the domain of literary criticism.

To my knowledge, this is the first international meeting on quantitative literary criticism held in Italy, where we are happy to test a new or updated model of in terpretation of literary texts. This initiative follows the 2014 Atelier doctorale de Textométrie held at the Ecole Française in Rome [1] and – back in 2006 – a series of yearly DIGIMED conferences or seminars on digital philology and computing archival sciences [2], all con nected to the Master in “Digital Edition”[3] and initially promoted by Dept. of Classics and Cultural Heritage in Arezzo, now by Dept. of Philology and Criticism of the Ancient and Modern Literatures of the Siena University and by the Ph.D. School in Philology and Criticism, whose head professors Bettalli and Pellini send their greetings. This meeting is thus a part of a series of initiatives on methods and experiences in the application of digital tools and environments to literary and historical studies.

The seminar is sponsored by the Committee for the History of Comparative Literature in European Languages (CHLEL), which has met here in this monastery over the past two days, and which has just edited a volume on literary hybrids [4] that will also be the subject of one of the round tables of the conference. The Committee is represented here by its President Prof. Marcel Cornis-Pope, whom I warmly thank. The other partner is the Italian Associazione per l’Informatica Umanistica e le Cultura Digitale (AIUCD), here represented by its President Fabio Ciotti, who helped me organize this seminar. I also thank Emanuela Piga, one of the directors of the electronic journal for compara tive literature Between, also discussed in one of the seminar’s presentations.

The title we have chosen is a variation of The Mechanic Muse, a well known book by Hugh Kenner [5] that looks at the close kinship of modernist writers with the technologies of their time. The title lent its name to a permanent column in the New York Times, later adapt ed in Italy by the «Corriere della Sera» [6], in which the latest digital humanities news is regularly commented.

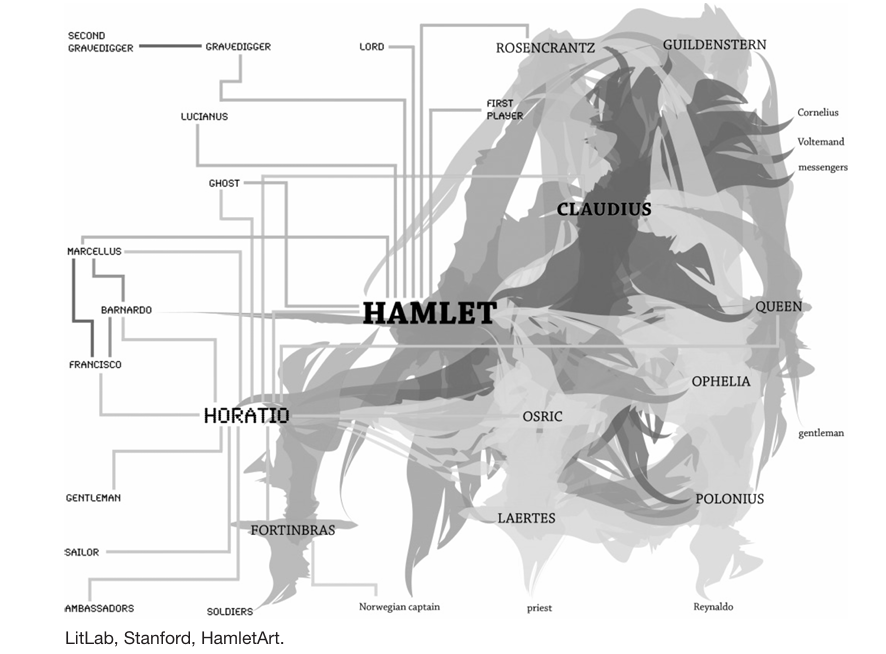

The Mechanic Reader refers to methods of textual analysis involving data mining, lexical statistics, frequency percentages, graphic processing of linguistic clusters or semantic networks, topic modelling, and so on. As Fabio Ciotti pointed out in his last article in Between, “the groundbreaking steps in this direction are due to researchers of the Stanford Literary Lab, founded and directed by Franco Moretti and Matthew Jokers” [7], and we all know that it was especially Moretti who gave this kind of research visibility and acknowledgment in his Distant reading, which will also be the subject of a round table this afternoon [8]. I have the impression that thanks to Moretti’s network analysis, certain literary phenomena, such as the role of Horatio in Shakespeare’s Hamlet, or the distribution of the characters in Dickens’ novels or Sophocles’ Antigone, were highlighted and even formulated in a way that would have been unthinkable by any other kind of literary analysis. It’s only through corpus observation that we become aware of the simple fact that literary theory has only concerned 1% of published novels, just the surface of literary produc tion. The Stanford LitLab demonstrated, or rather it reminded the forgetful literary community, that many literary features are not evident to the naked eye and that enquiries into textual corpora, often improperly called “big data”, can highlight connections and features that we could not even imagine and verify hy potheses that we could not draw from impressions, tastes or samples.

Above all, Moretti showed that the quantitative (not necessarily digital) systems for examining literary phenomena, systems which are not new but are now much better equipped and fashionable, need critical competence and skills, if not always Moretti’s undeniable ingeniousness and confidence, to extract a sense from such data and link it to a historical cul tural context. Automation of the data acquisition procedure is just an apparent result and does not grant any critical usability of the data itself. Moretti’s 2013 book and his subsequent 2014 article Operationalizing [9], awarded with the American Prize for Literary Criticism, proved to a wider audience that the meth od can have many deficiencies, including failure to weigh the ‘edges’ (i.e. the network connections), the absence of semantization and the need to manage tools that are often beyond the control of the average scholar; yet from close reading to structuralism and deconstructionism and so on, the key to their success, as with any other method, is the scholar’s ability to use it, to ask it the right and most productive questions in a consistent way, thus highlighting hitherto undetected aspects of the texts.

I have heard and read some odd and defensive objections to the reliability of these methods [10], which reminded me of criticism against Wikipedia and other internet sources: all of it was based on the unproven assumption that the paper encyclopaedia was exempt from errors, while we all know that the Encyclopaedia Britannica and Treccani volumes teem with errors, not to mention less prestigious enterprises on paper. In the same way, criticism of distant reading seems based on unproven assumptions that more traditional methods and other digital methods are free from errors, abuses, shortcuts. In quantitative criticism such dangers lie in the reader, not in the reader-device. We are here to improve the lenses of our reader device, whatever it may be. The assumed explosion of interest in literary analysis based on computing tools cannot be reduced to its most fashionable side, namely so-called big data mining, and the first of the errors to sweep away is that of grounding the method exclusively on data that meets the quantitative definition of “big data” [11]. Literature is literature, whatever the quantity of it, and we must discover and develop statistical laws (for example derogating from the χ square test for data that is not casually but intentionally produced, such as liter ary texts) that even work under this level instead of only applying them above it, as happens in medical or demographic statistics. The same caution is required regarding the composition and treatment of the data set under observation, which is not always Moretti’s point and which on the contrary should always be ex plained: [12] one should avoid making big efforts just to close the hermeneutic circle confirming by quantitative metrics what ‘intuitive’ criticism had already singled out [13].

In general, the most immediately valuable advantage of the attention drawn to distant reading is that it ‘refreshes’ the significance of the use of quantitative methods in the history of literary criticism, first of all in authorship attribution, stylometrics, lexical analysis, namely what we can still call a form of close reading [14]. The real problem is that if we want to challenge or in any way discuss the results of research which claims to be objective, we not only need a general knowledge of literary history and in-depth knowledge of the works (and languages) under observation, but we should have even some technical abilities that are neither common nor easy to acquire. The spread of amateurish use of digital analysis, amateurish in what concerns of the so-called professional literary scholar, however technically skilled, is therefore an insidious danger we can tackle only by mastering the methods. [15] The opposite is repeated by Moretti in his frequent warnings about his possible overestimation of network analysis results and his lack of technical competence [16].

On a personal level, I have been interested in theseapplications since 1999, when researching medieval Latin texts with disputed authorship, such as the ninth century poem Karolus magnus et Leo papa [17] or the twelfth century letter collection Epistolae duorum amantium [18]. I obtained some results that seem to have been accepted by the scholarly community, but I have experienced how much even relatively simple frequency analysis reveals about the work room of literary authors and about the development of languages. This is why we decided to set up this initiative: not to present the progress of our work or our team, which are not involved in the program, but just to get new impulses and explore new methods. So this is not the kind of conference we organized at other times, meetings for 150 to 400 people with two or three volumes of proceedings, but it is what EU bureaucratic language would call an ‘exploratory workshop’, which I consider a working tool far more effective than big conferences.

Again I feel a gap between the Italian situation and how the development is felt in other areas. In a very good application of a European program to which I subscribed, I read: «The easy availability of massive amounts of data creates an irresistible pressure to wards over-systematization and over-empiricism. Humanities researchers have compelled to quantify whatever can be quantified, in a drive toward a more ‘scientific’ form of research, even while the significance of the quantitative results remains very tendentious (Sculley and Pasanek 2008 [19], Liberman 2010 [20]). This is doubly a problem because much of the data relevant to research in the humanities is not easily systematizable – it has many ‘cases’ and multiple interpretations. These interpretations are key to the work that is done in most of the field of the humanities (Drucker 2011) [21], but they are in many cases exactly what is not easily digitized. In the face of this pressure, many scholars in the humanities are not engaging with the possibilities of digitally-enabled research at all, but are instead retreating back to their pencils, protesting an academic political environment that seems to demand them to compromise their principles of reason and argumentation in service to a pseudo-experimental approach to their fields. On the other hand, as more academic disciplines become more data intensive, this resistance to empirical methods by many humanities researchers is interpreted outside the field as evidence of the back wardness and irrelevance of the humanities (Courant et al., 2006 [22])» [23].

In my opinion it is the same as the resistance that occurred when structuralism took the place of stylistic criticism, when cultural studies took the place of structuralism, and so on. It is not an issue about machines vs. humans, but of experimental vs. established methods, and therefore more comfortable customs and practices.

In comparison with such caution, the Italian situation appears to be reversed: while the very few insiders are constantly running after the latest technological fashion (especially developing a discourse about encoding standards), 99% of ‘humanists’ (including digital humanists), and literary critics in particular, have never tried to apply even the oldest and most stable of the new technologies for interpretative purposes. Some thing has been done rather on the philological side, e.g. by Paola Italia regarding Manzoni, [24] and especially in authorship detection: Paolo Canettieri re Dante’s or Brunetto’s Il Fiore [25], Maurizio Lana re Gramsci’s news papers articles, [26] Federico Condello re Montale’s Diario postumo [27] and a few others, but almost nothing has been done on the critical or literary side [28]. So a paradox is arising: on one hand, outsiders do not have the time or will to learn and apply certain methods, and on the other hand the connoisseurs already consider some such methods out of date and are learning the next one [29]. Technology depends on market laws, that subject it to the constraint of unceasing –though in some cases merely apparent – innovation, because it must offer new commodities to consumers; so ‘humanists’ retire outside the flow of these new possibili ties into a kind of ghetto. This is particularly true in Italy, where literary criticism is having a dreadful crisis. So I see the so-called ‘digital turn’ as a chance for recharge not to miss, not just to remain in the mainstream but to emerge from stagnation and to revitalize stale methodological commonplaces. We have to master the tools and launch a remediation of critical reading. The new tools may be fit to test the good old trends and free them from the weight of critical arbitrariness that none of them can bear, in this anti-hierarchical era devoid of any acknowledged authority.

Literary data (and data in general) is not self-evident: someone has to make it visible and audible [30]. This of course requires observers with technological open-mindedness, but first of all observers with literary education and skills, who have literary questions to ask of it.

Notes

1 http://www.efrome.it/actualite/atelier-doctoral-histoire-et informatique-textometrie-des-sources-medievales.html.

2. http://www.tdtc.unisi.it/digimed/.

3. See www.infotext.unisi.it.

4. M. Cornis-Pope (ed.), New literary hybrids in the age of multimedia expression. Crossing borders, crossing genres, Amsterdam-Philadelphia, John Benjamin Publishing Company 2014.

5. Hugh Kenner, The Mechanic Muse, Oxford, Oxford University Press 1987.

6. We refer to the survey of the Sunday cultural supplement La lettura called Visual Data.

7. Between 2015.

8. F. Moretti, Distant Reading, London and New York, Verso 2013, Kindle Version 2014.

9. F. Moretti, Operationalizing. On the function of measuring in Literary Theory, in «New Left Review» 84 (Nov-Dec 2014), pp. 103-19.

10 Just one example: A.R. Galloway, Everything is computational, in «Reset», June 27th, 2013. Some of these positions are echoed in some passages of a couple of contributions in this same conference.

11 About the dangers of working with big data in literature see Jonathan Freedman, “After Close Reading”, also dealing with Mark Algee-Hewitt, Mark McGurl, Stanford Literary Lab, Between Canon and Corpus: Six Perspectives on 20th-Cen tury Novels. Pamphlet 8, Jan. 2015, http://litlab.stanford.edu/ LiteraryLabPamphlet8.pdf.

12 See again Freedman.

13 The remark «true, but trivial» made by a Columbia student goes this direction, as reported by James F. English in his Morettian Picaresque («Reset», June 27th, 2013).

14 I totally agree here with Freedman: «distant reading doesn’t just have a guilty, complicitous secret-sharer relation to soi-disant close reading: it depends on it.». Even Ross (quoted below) writes «surface reading, distant reading, and DH do not op pose close reading per se, but rather certain kinds of inter pretation habitually associated with (but not inherent to) close reading. Pursuing these new forms of analysis does not automatically exclude close attention to the sentence-level details of form and style; indeed, moving back and forth between the microscopy of close reading and the wide-angle lens of distant reading would enrich both methods, creating a dual perspecti ve that boasts both specificity and significance».

15 Such danger is what Shawna Ross warns us against when she talks of «compromises» that «could devalue DH work» in her review of Moretti’s book, which collects citations from many essays against DH applications to literature.

16 This is highlighted by Ross: «He admits some of his work “may well have overstated its case” [p. 119], muses at ano ther juncture “I may be exaggerating here,» [op. cit., p. 228], and laments that his lack of technical skills drove him to hand draw his visualizations in the early stages of distant reading. «This is not a long-term solution, of course,»he remarks of the hand drawings, but instead a characteristic of «the childhood of network theory for literature; a brief happiness, before the stern adulthood of statistics» [ibidem, p. 215].

17 F. Stella, «Autor und Zuschreibungen des sog. Karolus Magnus et Leo papa», in Nova de veteribus. Festschrift P.G. Schmidt, Berlin, de Gruyter 2004, pp. 155-175 (first published in Italian as presented at a 1999 Conference in Paderborn in Am Vorabend der Kaiserkrönung. Das Epos “Karolus magnus et Leo papa” und der Papstbesuch in Paderborn 799, ed. P. Godman-J. Jarnut-P. Johanek, Berlin, Akademie Verlag 2002).

18 F. Stella, «Epistolae duorum amantium»: nuovi paralleli testuali per gli inserti poetici, in «The Journal of Medieval Latin» 2009, pp. 374-97 and «Analisi informatiche del lessico e individuazione degli autori nelle Epistolae duorum amantium (XII secolo)», in 8th International Conference on Late and Vulgar Latin (6th-9th Oxford), ed. R. Wright, Hildesheim 2008, pp. 560-569. A more recent development is F. Stella, «Generic constants and chronological variations in statistical linguistics on Latin epistolography», in Analysis of Ancient and Medieval Texts and Manuscripts: Digital Approaches, ed. Tara Andrews-Caroline Macé, Turnhout, Brepols 2014, pp. 159-79.

19 D. Sculley and Bradley M. Pasanek, Meaning and Mining: the Impact of Implicit Assumptions in Data Mining for the Humanities, in «Literary and Linguistic Computing», 24/4 (2008).

20 Fred Jelinek in «Computational Linguistics» 36(4), Dec. 2010, pp. 595-9.

21 «Humanistic Theory and Digital Scholarship,» in Debates in Digital Humanities, forthcoming.

22 P.N. Courant et al., Our Cultural Commonwealth: The report of the American Council of Learned Societies, Commission on Cyberinfrastructure for Humanities and Social Sciences. University of Southern California, 2006.

23 Text by Tara Andrews and Joris van Zundert, unpublished.

24 See her contribution in this volume and what she published in the proceedings of the Bologna AIUCD conference 18-19th September 2014 La metodologia della ricerca umanistica nell’ecosistema digitale: Paola Italia and Fabio Vitali, “Varianti testuali e versioning fra bibliografia testuale e informatica”, forthcoming.

25 Paolo Canettieri, Il Fiore e il Detto d’Amore, in «Critica del Testo», 14/1 (2011), pp. 519-30.

26 C. Basile, M. Lana, L’attribuzione di testi con metodi quanti tativi: riconoscimento di testi gramsciani, «AIDA Informazioni» 26 (2008), pp. 165-89.

27 F. Condello in the Proceedings of the AIUCD Bologna Confe rence 18-19th September 2014 La metodologia della ricerca umanistica nell’ecosistema digitale: Federico Condello and Mirko Degli Esposti, «La authorship attribution fra filologia e matematica«, forthcoming.

28 Even the useful guide Linguistica dei corpora by M. Fred di, Roma, Carocci 2014 overlooks the literary side. A pioneering attempt is Fabio Ciotti, Il testo e l’automa. Saggi di teoria e critica computazionale dei testi letterari, Aracne 2007, which deals above all with the encoding issues and for chronological reasons, could not take the new methods into account.

29 This is one of the most evident limits of Italian DH worshippers: placing fashionabilty before substantial results and research quality, by defining every previous method as dated. But it’s not just an Italian problem. Amanda Gailey and Andrew Jewell warned against the attitude of considering “the quality of work...not so important as staying at the edge of innova tion” [Editor’s Introduction to «Scholarly Editing» 33 (2012), pp. 1-7, at p. 5].

30 As Moretti p. 240 points out, «an enormous amount of empirical data must be first put together. Will we, as a discipline, be capable of sharing raw materials, evidence – facts – with each other? It remains to be seen».

¬ top of page