« indietro

In Zanzotto e le lingue altre, Semicerchio LXVIII, 2023, pp. 24-32.

"Duty Free": Notes on the English of Andrea Zanzotto

di John P. Welle

In the essay, Il mio Campana (2011), Andrea Zanzotto discusses his youthful discovery of Hölderlin, Rimbaud and Campana, all at the same time. In reflecting upon «il problema semantico, imposto dalla diversità delle lingue»[1], he summarizes his experience of the learning of languages:

In realtà, non ho mai appreso completamente alcuna lingua e mi sono sempre più considerato un botanico delle grammatiche piuttosto che un vero e proprio conoscitore di lingue e di teorie del linguaggio. In compenso, mi sono salvato da questi deficit linguistici di tipo ... duty free imparando a memoria una quantità eccezionale di poesie, per lo meno millecinquecento, duemila versi distribuiti in varie lingue[2].

What interests me here, rather than the botanical metaphor that other critics have examined to good effect[3], is Zanzotto’s utilization of English words and expressions, such as «deficit» and «duty free». They help make his point with the kind of ironic rhetorical precision characteristic of his style. However, when we begin to point out that the poet is speaking ‘tongue in cheek’, we pull back. We realize he has already beaten us to that spot. In a dialogue entitled Tra passato prossimo e presente remoto, he ‘flips the script’ by translating the English idiom into Italian and placing it between quotation marks «lingua contro guancia»[4].

Zanzotto’s use of English words and expressions, as in the cases indicated above, invite closer analysis. The poet himself has commented upon his relationship to the English language, in numerous places, particularly with regard to Haiku for a Season / per una stagione. He expressed himself in these words to Marzio Breda: «Li componevo in un inglese ridotto quasi al grado zero, minimo e minimalista, perché quella lingua la conoscevo poco ma mi piaceva esplorarla»[5].

While the haiku remain, in Breda’s formulation, «un capitolo piuttosto misterioso nella sua vasta opera»[6], we should not lose sight of the fact that Zanzotto’s other works already contain extensive use of English words and idiomatic expressions[7]. Also relevant here are the not infrequent references in his critical works to Anglo-American and Irish writers, beginning with his thesis at the University of Padua in 1942, Il problema critico dell’arte di Grazia Deledda, which contains allusions to Aldous Huxley (p.22), Anna Radcliffe (p.40), D. H. Lawrence (p. 71), Ralph Waldo Emerson (p. 86), Caterina Mansfield (p.88), Jack London (p.08), Erskine Caldwell (p. 183), John Steinbeck (p.183), and J. M. Barrie, the author of Peter Pan (pp.186-87)[8].

Already beginning in the 1960s, with the publication of La Beltà (1968), we find him reflecting on «il disagio nei confronti delle lingue in uso e degli imperi linguistici, [...] nel ‘villaggio elettronico’ mondiale [...]. Quindi tendenza al babelismo, alla contaminazione interlinguistica e, insieme, alla visualizzazione, al grafismo, agli ideogrammi»[9]. He also writes at length on his perceptions of the current state of English in a globalized world in such essays as Europa, melograno di lingue, where he reflects on the universal presence of English, on the emergence of ‘broken English’, and on «un possible, e già ipotizzato, super-pidgin mondiale anglo-cinese»[10]. He has also written extensively about the negative impact of English on Italian and on the resulting weakening of national identity: «E qui si fa avanti il problema odierno, della scomparsa dell’affetto, si fa per dire, alla propria lingua nazionale, col suo glorioso corteo di dialetti [...] lingua minacciata a valanga da un ‘anglosassone’ sempre più invasivo e sbrodolone»[11].

Most notably, Stefano Dal Bianco has written with insight on this topic. Regarding the presence of English in Zanzotto’s poetry, for example, with the exception of Haiku for a Season/ per una stagione, he offers the following synthesis:

L’inglese è trattato regolarmente con disprezzo da Zanzotto. È la lingua dell’alienazione, e non compare mai senza una componente di sarcasmo o di violenza. È la lingua bastarda della pubblicità, della contaminazione, della plastica, del trash, del fumetto, dei prodotti commerciali [...] è la lingua della guerra fredda, del potere e dell’imperialismo americano, dell’economia, dell’usura, del denaro simbolico, della sofisticazione. E poi è la lingua dell’irrealtà virtuale, di internet. L’inglese è una poltiglia linguistica, un gel, una lingua-detrito massificato. Non faccio esempi, che sono dappertutto[12].

While I agree with Dal Bianco’s overall assessment, I sense that he paints here with too broad a brush.

In fact, more recently, Dal Bianco himself provides a cogent, succinct and revised summary of the status questionis. Contrasting the English of the Haiku with that of the preceding and subsequent volumes, he writes: «Incredibilmente, l’inglese di questi Haiku è invece del tutto pacifico, del tutto innocente e anzi un po’ childish, un po’ bambinesco. […] In ogni caso, una certa ambigua e sotterraneamente inquietante fascinazione per la lingua inglese esiste in Zanzotto»[13].

Following Dal Bianco, I am interested in exploring Zanzotto’s «ambiguous and […] perplexing fascination» with English. While such a complex subject matter merits a more sustained analysis than can be undertaken here, the notes I offer point towards a few unexamined topics with the hope of creating ‘spunti’ that might stimulate further discussion.

One component of the English of Andrea Zanzotto that has received scant attention involves his remarks on the Anglophone characteristics of other Italian writers[14]. Ugo Foscolo provides a case in point. Zanzotto has dedicated no fewer than three articles to his illustrious compatriot with whom he shares linguistic and other affinities. In Omaggio al poeta, for example, which was published in 1978, at the height of the Italian ‘years of lead’ when national identity and national unity were being tested, he observes:

Poco o nulla sappiamo della parlata quotidiana del Foscolo, anche se si hanno invece molte testimonianze di frasi pronunciate in momenti eccezionali. Possiamo immaginarlo, con probabilità, parlante in un veneto coloniale, in un dialetto veneto-orientale dotato di una vivissima forza espressiva nella quotidianità: o egli già aveva ‘fatto il salto’ direttamente verso una forma di italiano? Purtroppo non conosco nulla in proposito[15].

Probing Foscolo’s sense of identity as the son of a Venetian father and Greek mother, who would spend the tragic final years of his life in exile and in poverty in and around London, Zanzotto pens this succinct characterization: «Ugo Foscolo, greco, veneziano, italiano, ‘inglese’»[16].

Well known for his longstanding interest in languages, Zanzotto digs deeper into the subject matter:

Nell’inconscio del poeta [...] si aggrovigliano [...] numerose lingue/patrie. C’è in Foscolo ad esempio colui che usa come lingua veicolare ed epistolare in modo abbastanza elegante il francese; c’è un Foscolo che conosce l’inglese, non si sa quanto, ma che importa sapere “quanto” lo conosca? Chi conosce una lingua? Nessuno[17].

Zanzotto’s speculations concerning Foscolo’s linguistic competencies are relevant to our own inquiry. How ‘well’ did our «botanist of grammars» know English? By his own admission, not as well as he would have preferred[18]. Do such qualifications matter? The evidence – his extensive use of English in poetry, prose and criticism (not to mention the Haiku) – suggests they do not.

In a letter to the present writer (May 5, 1986), Zanzotto remarked on some materials in English that I had forwarded, which I thought might be of interest to him:

Molte grazie delle pubblicazioni, entrambi interessanti nei loro diversi motivi. Purtroppo le mie conoscenze dell’inglese non sono tali da permettermi di leggere gli autori direttamente. Io ho sempre usato testi con traduzione a fronte, anche per poter far più precisi riscontri. Duncan mi è noto abbastanza e lo credo di grande valore[19].

In another letter (March 22, 1992), Zanzotto commented on the editorial problems regarding Ezra Pound’s works in Italy. In an article on Dante in the pseudo-trilogy[20], I had cited Zanzotto’s inaccurate quotation of Canto CXX.

Trovo che hai messo un (sic) in una citazione di Pound. Forse è sbagliato? Purtroppo non riesco ad avere il testo definitivo del conclusivo Canto CXX. So che c’è una questione in proposito, anche sulla sua autenticità; ti sarei grato di tue informazioni[21].

These fine points – minutiae even – would seem to be of little importance. And yet, they beg the larger question of Zanzotto’s relationship to the great modernists in the Anglophone canon, especially those most influenced by Dante, namely Joyce, Pound and Eliot[22]. For example, in an exchange with Stefano Verdino, Zanzotto states: «Eliot ha contato anche per me, come, penso, per la maggior parte di quelli della mia generazione. Ma sono vaghe e sotterranee irruzioni e vene»[23]. Moreover, very little research has been done on his relations with contemporary English-language poets such as Robert Duncan and Michael Palmer cited above, to name only two[24].

With regard to James Joyce, an interesting component of Zanzotto’s English involves his close engagement in the translation of Filò[25]. In our epistolary exchanges, for example, various choices for a title to the work were discussed. Zanzotto clarified his intentions in a letter to the present writer (June 29, 1990):

Se ti pare che “Wake” non vada bene, si potrebbe sostituire con Talks, come tu suggerisci (anche se mi pare che nel titolo joyciano la sfumatura funebre non risulti evidente – e del resto, l’allusione a Joyce sarebbe più utile)[26].

In suggesting the title Peasants Wake, Zanzotto distinctly echoes Finnegans Wake. With a touch of elegance, he intends to send forth Filò in a trilingual edition (Solighese, Italian, English) under the sign of an iconic modernist, James Joyce. The rich polysemy of the original title also becomes mirrored in translation through the famous missing possessive apostrophe: Finnegans [‘] Wake / Peasants [‘] Wake, to comment on only the most basic level[27].

Returning to Zanzotto’s observations on Ugo Foscolo’s command of English, we should underline his emphasis on his role as a translator: «Esisteva comunque un Foscolo inglese, capace di tradurre un autore come Sterne (con un tipo di libertà, che si potrebbe paragonare a quella, così produttiva, di Pavese o Vittorini)»[28].

As is well known, Ugo Foscolo’s free translation of Lawrence Sterne’s A Sentimental Journey in France and Italy (1768) would have a profound impact in Italian literature; it created what Giancarlo Mazzacurati has termed the «Sterne effect», a humorous vein in Italian narrative built upon digression and self-reflexivity[29]. «Today», Olivia Santovetti writes

the ‘Sterne effect’ is clearly visible in the catalogues of most Italian publishing houses, that feel compelled to have Sterne in their collection. In the bookshops in Italy one may choose between three editions of Tristram Shandy [...] and eight editions of A Sentimental Journey [...] It is clear that Sterne has reached classic status in Italy[30].

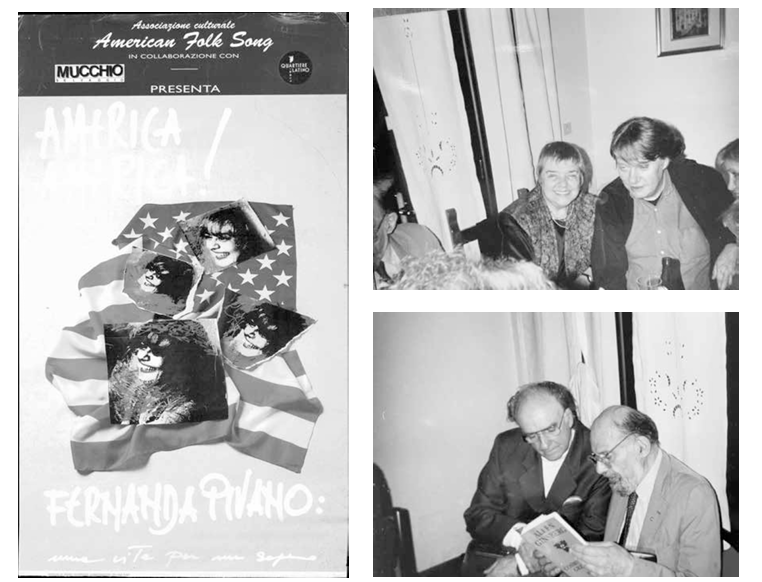

Furthermore, Zanzotto’s meditation on Foscolo’s English prompts him to reference Cesare Pavese and Elio Vittorini as translators. The Piemontese writer’s versions of American authors in the 1930s and 1940s were prodigious and we need not list them here. Moreover, Pavese’s young protégé, Fernanda Pivano, would translate Edgar Lee Masters’ Spoon River Anthology (1915) for Einaudi in 1943. After this auspicious beginning, she would embark on a distinguished career as a poet, journalist, writer, and translator who was chiefly responsible for the diffusion of leading American authors in Italy. Perhaps she is best known today for her versions of the Beat Generation writers of the 1960s, Jack Kerouac, William S. Burroughs, Gregory Corso, Lawrence Ferlinghetti, and in particular, Allen Ginsberg[31].

Moreover, Zanzotto’s fecund comment on Foscolo’s English translations leads him to reference a second modern Italian writer/translator: Elio Vittorini. A fine point regarding the publication of Ginsberg’s Jukebox all’idrogeno (1965) sheds light on an important collaboration involving Ginsberg, Pivano and Vittorini.

At Mondadori, Elio Vittorini was the director of the series Nuovi Scrittori Stranieri, which was to publish Jukebox all’idrogeno. Vittorini was in charge of the publication of Ginsberg’s anthology, and Pivano mediated between the editor and the author on editorial matters and the choice of title. In fact, the agreed title – Jukebox all’idrogeno – was the result of a series of negotiations between Ginsberg and Vittorini[32].

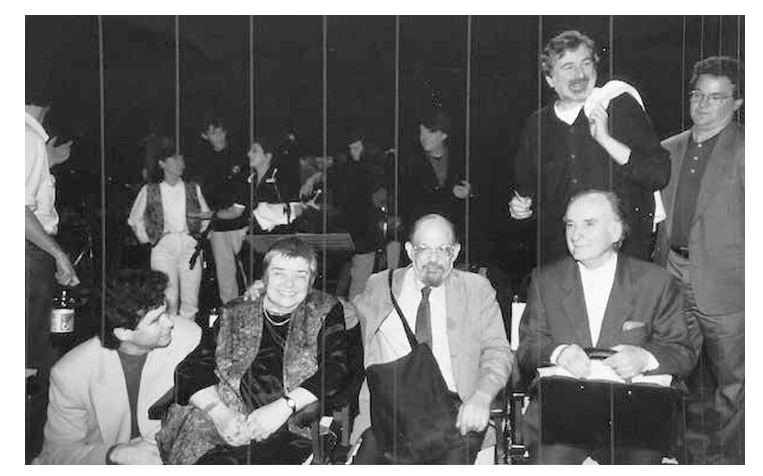

When she retired, she was celebrated at Coneglia no Veneto in June of 1995 with a two-day «Tributo a Fernanda Pivano»[33]. Distinguished participants in this event included Fabrizio De André, Allen Ginsberg, Francesco Guccini, Jay McInerney, Pivano, and Andrea Zanzotto, among others. In the photographs that follow, we see her during a moment at dinner with Fabrizio De André before going on stage for the Saturday evening encounter involving speeches, poetry, music and translation. She delivered her remarks on this occasion to a packed theatre. In other photos, Zanzotto and Ginsberg are seen at the same dinner, on June 10, 1995. The two poets were overheard conversing in French.

Back in 1981, Zanzotto had this to say with regard to Allen Ginsberg, England, America, poetry, young people, and popular music:

Si dice che in Inghilterra e in America vanno a migliaia a sentire i poeti che cantano le loro canzoni; ma è necessario distinguere: spesso l’ascolto lo hanno quelli che sono ‘cantautori’ più che poeti. Anche Ginsberg fa concerti di questo tipo, accompagnato da un piccolo gruppo musicale, e non si tratta certo di spettacoli scadenti; ma il Ginsberg attuale non è confrontabile con quello di venti anni fa, quando ha scritto le sue opere maggiori[34].

In fact, while on stage at Conegliano, Ginsberg delivered his poetry with considerable intonation, even singing at times and also playing the harmonium. Zanzotto’s intervention touched upon translation, as was fitting for the occasion. I had the honor of reading a version of Charlot e Gigetto in English, which I had developed in collaboration with Ruth Feldman. For their part, the cantautori, who participated, De André and Guccini, along with the Italian rock group, ‘The Groovers’, performed musical numbers independently of the literary figures.

Zanzotto’s comments on Allen Ginsberg’s English, and specifically his criticism of his American counterpart’s lowering of the intensity of poetic language, are worth noting: «Basta pensare a Ginsberg che, da poeta rivolto a cercare i valori formali tipici della poesia, si è trasformato in propagandista ambulante di una ideologia pacifista, utilizzando un linguaggio che potrebbe essere benissimo quello di un buon giornalista»[35].

Some two decades earlier, in the process of composing the poem D’un fiato, Zanzotto had included, in the first two drafts, a reference to Allen Ginsberg. Working from archival sources, Luca Stefanelli sheds light on the issue at hand

Tra gli appunti della Beltà, si trova inoltre un foglio (V/II, 5) in cui il poeta annota [...] una serie di nomi riconducibili al filone soprattutto francese, ma anche americano, di poeti e scrittori che legarono le loro opere all’esperienza delle droghe [...] Troviamo il nome di Michaux, accanto a quello di William Burroughs, nella prima redazione di D’un fiato, dove una variante aut. aggiunge all’elenco anche Allen Ginsberg, sostituito poi definitivamente da Timothy Leary a partire dalla terza stesura[36].

The passage from D’un fiato, in its definitive third version with Timothy Leary substituted for Allen Ginsberg, published in Pasque (1973), reads as follows:

la fräulein si vocalizza usignuolizza in inviti

(e lui Leary Burroughs e Michaux

nel fossato butta via butta gìu

barbume barbume che non ci sta pìu[37];

Zanzotto may have had any number of reasons for substituting ‘Leary’ for ‘Ginsberg.’ At first glance, however, one notices the repetition of the consonant ‘L’ – «e lui Leary». Alliteration plays a big role in this poem. The stress on sound might be the simplest explanation for Ginsberg’s elimination from the definitive version of the text.

As the passage cited above from Stefanelli indicates, Ginsberg, along with William S. Burroughs, Timothy Leary, and Henri Michaux, are all associated with the theme of hallucinogenic drugs and literature. To be sure, Michaux, whom Zanzotto deeply respected, and with whom he felt a close affinity, seems to be of greater relevance on this topic for him than the American writers.

In addition to penning two articles on Michaux in 1960 and 1966, Zanzotto translated a long section from the poem, La mescalina e la musica[38]. Michaux, a French-Belgian writer, took hallucinogenic drugs under medical supervision and wrote about their effects on his perceptions and consciousness[39]. In a letter dated February 6, 1960, to Giambattista Vicari, the editor of the literary journal, «Il Caffè», Andrea Zanzotto wrote: «Vorrei scrivere su Michaux, specie sull’ultimo. Ma è una cosa tremenda. Io gli somiglio troppo nei difetti senza avere nemmeno una pallida ombra dei suoi pregi, della sua forza»[40]. In another letter to Vicari from January 3, 1960, Zanzotto indicates having read Michaux’s «resoconto sulla psilocibina» and having found it to be «come sempre, emozionante»[41].

In English, the effects following the ingestion of psychedelic drugs are known colloquially as ‘a trip.’ The Oxford English Dictionary lists ‘trip’ as a slang word originating in the United States: «A hallucinatory experience induced by a drug, especially LSD»[42]. As an example of the term, the OED cites Norman Mailer’s book, Advertisements for Myself, published in 1959: «I took some mescaline... At the end of a long and private trip which no quick remark should try to describe, the book of The Deer Park floated into mind»[43].

In the lexicon of Zanzotto’s English, the word «trip» seems to possess a particular fascination. Although it is not possible to display the evidence here, this term re-occurs repeatedly over a remarkable half century of poetry, criticism and commentary [44]. Let the following example from the Haiku stand for many:

Within stars and trips

within gems and tears

an ‘I’ remakes as a movie its ‘I’

Tra stelle e viaggi

tra gemme e lacrime

un ‘Io’ rifà come film il suo ‘Io’[45]

In the line «Within stars and trips» we may also hear an echo of the familiar description of the American flag, ‘stars and stripes’[46]. While a compendium of Zanzotto’s poetic diction remains a task for future scholars, in the meantime, we might propose «trip» as a key word along with such familiar lexical items as «faglia», «pae saggio», «bosco», «infinito», etc.

Moreover, the word «trip», as it appears in Zanzotto’s writings, can also serve as a metonym for the act of writing poetry itself. The following statement provides necessary context:

in fondo in fondo chi scrive poesia ha sempre anche la vecchia tentazione della felicità, sia pure sotto la specie (infame?) del ‘paradiso artificiale’, da ottenere via droga – droga verbale. Così, se il discorso non appare nitido, non appare chiaro ad una prima lettura, si chiede almeno l’attenuante di una buona fede in chi se ne è fatto tramite, in chi è stato ‘parlato’, ‘attraversato’ da questo discorso che è insieme storiografia e trip da droga (per così dire) – che ha insieme questi due aspetti in apparenza così antitetici e invece connessi in una misteriosa radice[47].

As this statement indicates, and as is well known, poetry for Zanzotto constitutes an event. In the process of writing, the poet touches a margin, an outer limit, in an action that is both historiographic and transcendent. Here and elsewhere, the poet employs the American slang word «trip», and the experience it conveys, as an essential element of his meta-poetic discourse[48].

By way of conclusion, allow me to share a personal reminiscence regarding the English of Andrea Zanzotto. In June of 1989, my wife, Mary Kay Schanhaar Welle, and our two children, Katie and Andrew, who were 6 and 4 at the time, respectively, accompanied me during a visit to Pieve di Soligo. At a certain point, while we were conversing in the garden, Andrea Zanzotto went into the house and returned with a folder. He explained that he was writing haiku in English, a language that he did not speak, and that he would be honored if Katie would read some aloud so he could hear what the English sounded like. She read a half dozen of them in a clear voice to everyone’s delight and satisfaction.

This literary convivio, as Zanzotto called it, enlivened by the reading of a six-year-old child, brings to mind, and indeed would seem to embody, another of his many statements on English; one which is relevant for the Haiku, and with which I close: «si deve aggiungere che una lingua ‘universale’, l’inglese, per esempio, conserva parentele verticali, vocabolo per vocabolo, persino con il dialetto e, ancora più in basso, con la parlata della contrada, giungendo addittura all’idioletto personale: una dimensione linguistica panterrestre, insomma»[49].

[1] Andrea Zanzotto, Il mio Campana, edited by Francesco Carbognin, Bologna, Clueb 2011, p. 19.

[2] Ibid. pp. 19-20.

[3] Silvia Bassi, Un «giardiniere e botanico delle lingue»: Andrea Zanzotto traduttore e autotraduttore (tesi di dottorato), Università Ca’ Foscari, a.a. 2009-2010.

[4] Andrea Zanzotto, Tra passato prossimo e presente remoto, in Poesie e prose scelte (hereafter PPS), edited by Stefano Dal Bianco and Gian Mario Villalta, Milano, Mondadori 1999, p. 1376.

[5] Andrea Zanzotto, as cited by Marzio Breda, Alchimista della parola, in Andrea Zanzotto, Haiku for a Season / per una stagione, edited by Anna Secco and Patrick Barron, Milano, Mondadori 2019, p. 104.

[6] Ibid. p.105.

[7] Critical interest in Zanzotto’s English has begun to intensify in recent years, with particular, almost exclusive, attention to the Haiku. See Nicola Gardini, Linguistic Dilemma and Intertextuality in Contemporary Italian Poetry: the Case of Andrea Zanzotto, «Forum Italicum» 35.2 (2001) pp. 432-441, Andrea Cortelessa, Sotto la pelle delle lingue, in Andrea Zanzotto. La natura, l’idioma, edited by Francesco Carbognin, Atti del convegno internazionale, Pieve di Soligo-Solighetto-Cison di Valmarino, October 10-11-12, 2014, Treviso, Canova Edizioni 2018 pp. 187-202; Stefano Dal Bianco, Le lingue e l’inglese degli Haiku, in Nel «melograno di lingue». Plurilinguismo e traduzione in Andrea Zanzotto, edited by Giorgia Bongiorno and Laura Toppan, Firenze, Firenze University Press 2018, pp. 41 47; John P. Welle, Zanzotto in inglese: La vita letteraria come dialogo e corrispondenza, in Nel “melograno di lingue”: Plurilinguismo e traduzione in Andrea Zanzotto, cit., pp. 279-288; Niva Lorenzini, Approdi dello haiku nella poesia italiana tra fine del XX e avvio del XXI secolo, «Poetiche», XXI (2019), 1-2, pp. 33-41; Matteo Giancotti, Questioni preliminari agli ‘Haiku’ di Zanzotto, in Le estreme tracce del sublime: studi sull’ultimo Zanzotto, edited by Alberto Russo Previtali, Udine, Mimesis 2021, pp. 59-73; Matilde Manara, Diplopie, sovrimpressioni: Poesia e critica in Andrea Zanzotto, Pisa, Pacini Editore 2021, n. 56, pp. 109-10.

[8] Andrea Zanzotto, L’arte di Grazia Deledda, [1942], Padova, Padova University Press 2016. Matilde Manara provides insights on the thesis: «Dalla tesi traspaiono l’interesse per le dinamiche dell’inconscio; l’attenzione all’universo popolare e paesaggistico; una buona conoscenza della tradizione letteraria europea. Anche se viene attribuito a Deledda, questo bagaglio culturale è in realtà quello dell’autore». Matilde Manara, Diplopie, cit., p. 23.

[9] Andrea Zanzotto, Su ‘La Beltà, PPS, p. 1147.

[10] Andrea Zanzotto, Europa, melograno di lingue, PPS, p. 1350.

[11] Andrea Zanzotto, Tra passato prossimo e presente remoto, PPS, pp. 1373-74.

[12] Stefano Dal Bianco, Le lingue e l’inglese degli Haiku, cit. pp. 44-5.

[13] Dal Bianco’s remarks were occasioned by the recent theatrical performance in Pieve di Soligo on November 25th, 2022 of Interpretare Zanzotto: Haiku for a Season, which featured the New York-based multidisciplinary artist Helga Davis, original music by Andrea Liberovici, artistic direction by Lello Voce, and stage adaptation by these two, along with Stefano Dal Bianco. https://www.argonline.it/haiku-for-season-zanzotto-25-novembre-teatro-careni/ accessed on January 31, 2023.

[14] Related aspects of interest dealing with English and Italian are found in the following comments: «Goethe […] conosceva l’italiano quasi per eredità famigliare […] mentre non voleva saperne dell’inglese», and «la grande Elisabetta, parlava bene l’italiano, lo conosceva, lo leggeva». Andrea Zanzotto, PPS, p.1349.

[15] Andrea Zanzotto, Omaggio al poeta, Scritti sulla letteratura, Fantasie dell’avvicinamento, Vol. 1, edited by Gian Mario Villalta, Milano, Mondadori 2001, p. 308.

[16] Andrea Zanzotto, Isabella e i ‘Ritratti’, Scritti sulla letteratura, p. 319.

[17] Andrea Zanzotto, Omaggio, Scritti sulla letteratura, cit., p. 309.

[18] Andrea Zanzotto, letter to John P. Welle, dated 1984-85: «Per quanto mi riguarda, come le dissi, sto passando un periodo di depressione assai pesante, e non ne sono ancora uscito. Ho scritto qualche verso, ma quasi per mia ‘autoterapia’. In ogni caso il 3˚ volume-parte della pseudo trilogia è quasi (da tempo) finito. Quel poco che mi resta da completare o ritoccare mi sembra però un compito difficile. Per uscire dalle solite strade avevo anche tentato di scrivere degli haiku (per così dire) anche usando un inglese molto elementare, turistico, ma mi sembra una cosa mal riuscita, fallimentare. In ogni caso saranno serviti, coi loro strafalcioni, ad un po’ d’esercizio di inglese, lingua che purtroppo mi è scarsamente familiare. E sento ciò come una grave limitazione culturale». In addition to Braida and Dal Bianco, cited above, see also Andrea Cortelessa, Zanzotto il canto nella terra, Bari-Roma, Laterza 2021, pp. 249-253, for his useful term «deskilling» as an artistic strategy to characterize Zanzotto’s English in the Haiku.

[19] Andrea Zanzotto letter to John P. Welle, May 5, 1986. The American poet, Robert Duncan (1919-1988) was a leading literary figure and public intellectual. His pamphlet, Dante Études, appears as Number 8 (1974) in a series of fascicules, A Curriculum of the Soul, a project initiated by Charles Olson, for the Institute of Further Studies, Campden, New York. Duncan’s work inspired by Dante was published in Groundwork: Before the War. Vol.1, New York, New Directions, 1984, a volume which I sent to Zanzotto. A more recent edition of Duncan’s masterpiece combines volumes 1 and 2: Groundwork: Before the War / In the Dark, Introduction by Michael Palmer, New York, New Directions 2006. The internationally recognized poet, Michael Palmer is the author of a sequence of poems, Letters to Zanzotto, in At Passages, New York, New Directions 1995, pp. 1-12. In a letter dated January 16, 1996-97 to the present author, Zanzotto wrote: «Salutami di cuore l’amico Palmer (se hai l’indirizzo, mandamelo)». I am grateful to my colleague, Stephen Fredman for the bibliographical details cited above. See his masterful essay on Duncan, https://www.poetryfoundation.org/articles/148874/poetry-of-all-poetries.

[20] John P. Welle, Dante and Poetic ‘Communio’ in Zanzotto’s Pseudo-Trilogy, «Lectura Dantis» 10 (Spring 1992), pp. 34 58, p. 49.

[21] Andrea Zanzotto letter to John P. Welle, March 22, 1992.

[22] On Joyce and Zanzotto, see Fabio Pedone, Dall’infans alla lingua-omega: Zanzotto, Joyce. «Strumenti critici» n.1 (2020 April), pp. 135-58. Luigi Tassoni’s essay, Caosmos. La poesia di Andrea Zanzotto, [2002] Roma, Carocci 2021, remains fundamental in this context.

[23] Andrea Zanzotto, in T.S. Eliot e l’Italia, edited by Stefano Verdino, «Nuova Corrente» n. 36 (gennaio-giugno 1989), p. 19.

[24] John P. Welle, Zanzotto in inglese: La vita letteraria come dialogo e correspondenza, in Nel “melograno di lingue”: Plurilinguismo e traduzione in Andrea Zanzotto, cit., pp. 279-288.

[25] Andrea Zanzotto, Peasants Wake for Fellini’s ‘Casanova’ and Other Poems, edited and translated by John P. Welle and Ruth Feldman, Urbana and Chicago, University of Illinois Press 1997.

[26] Andrea Zanzotto letter to John P. Welle June 29, 1990.

[27] Concerning Joyce’s masterpiece, Zanzotto writes: «Joyce è riuscito a fondere e a far entrare in collisione principio e fine, coatto borbottio e parola inaudatamente libera, nella più terrificante e inebriante consapevolezza, con l’esperienza compiuta in Finnegans Wake». Tra ombre di percezioni “fondanti” (appunti), PPS, p. 1345. Zanzotto’s comments on Joyce’s famous construction ‘chaosmos’ are also relevant: «Per questa situazione si può benissimo riprendere il bel vocabolo joyciano chaosmos, caos e cosmos fusi insieme», Tentativi di esperienze poetiche (Poetiche-Lampo), PPS, p. 1734.

[28] Andrea Zanzotto, Omaggio al poeta, cit., p. 309.

[29] Giancarlo Mazzacurati, L’Effetto Sterne: la narrazione umoristica in Italia da Foscolo a Pirandello, Pisa, Nistri-Lischi 1990.

[30] Olivia Santovetti, The Sentimental, the ‘Inconclusive’, the Digressive: Sterne in Italy, in The Reception of Laurence Sterne in Europe, edited by Peter de Voogd and John Neubauer, London, Continuum 2004, pp. 193-220, p. 193.

[31] Andrea Romanzi, ‘L’urlo’ di Fernanda Pivano: The History of the Publication of Allen Ginsberg’s ‘Howl’ in Italy, «The Italianist» n. 41 (2021-2), pp. 424-445. See also Vanessa Chizzini, Fernanda Pivano e la letteratura americana del’900’ (accessed February 10, 2023).

[32] Romanzi, ibid., p. 10.

[33] See Jay McInerny’s description of this event, Grazie, Fernanda, in «The New Yorker», July 24th, 1995, p.30.

[34] Andrea Zanzotto, PPS, p. 1264.

[35] Ivi., p. 1281.

[36] Luca Stefanelli, Il divenire di una poetica: il logos veniente di Andrea Zanzotto dalla Beltà a Conglomerati, Milano-Udine, Mimesis 2015, p.50.

[37] Andrea Zanzotto, PPS, p. 419.

[38] Andrea Zanzotto, Traduzioni trapianti imitazioni, edited by Giuseppe Sandrini, Milano, Mondadori 2018, pp. 41-49.

[39] For Zanzotto’s relations with Michaux, see Matilde Manara, Diplopie, cit., n. 63, p. 34.

[40] Andrea Zanzotto, Traduzioni trapianti imitazioni, cit., p. X.

[41] Ibid. p. 282.

[42] OED Online, 2nd edition, Oxford, Oxford University Press 2000.

[43] Ibid.

[44] I presented an earlier version of this material, «Trip dentro trip»: Andrea Zanzotto’s Meditations on English, at the conference, «Conglomerati: Andrea Zanzotto’s Poetic Clusters», sponsored by Oxford University, November 18-19, 2021, organized by Adele Bardazzi, Roberto Binazzi, and Nicola Gardini, whom I wish to thank.

[45] Andrea Zanzotto, Haiku for a Season, cit., pp. 52-53.

[46] Another haiku contains associations with the Beat Generation of the 1960s: «Hippy crowd against the rain, / poppy revolution --- / where I was solitary-red / a red billion bangs» [Folla hippy contro la pioggia, / rivoluzione di papaveri --- / dove io ero solitario-rosso / un rosso miliardo esplode]. Ibid., pp. 58-9.

[47] Andrea Zanzotto, PPS, 1201-02.

[48] The most forceful, intense and extended use of the word ‘trip’ by Zanzotto is found in a series of compositions related to the poem Attraverso l’evento, published in Il Galateo in Bosco (1978). See Francesco Venturi, Genesi e storia della “trilogia” di Andrea Zanzotto, Pisa, Edizioni ETS 2016, pp. 70-74. Attraverso l’evento is also adapted as a title for two artists’ books, which comprise small anthologies that have largely escaped the attention of critics. See Andrea Zanzotto, Attraverso l’evento, con tre serigrafie di Armando Pizzinato, Venice, Edizioni Terraferma 1977; Attraverso l’evento, Immagini di Giosetta Fioroni, Poesie di Andrea Zanzotto, Mirano/Venezia, Edizioni Eidos 1988. I am grateful to Giovanni Zanzotto and to Silvana Tamiozzo-Goldmann for making it possible for me to view a variant of the poem, Attraverso l’evento in Pizzinato’s artist book. It bears emphasizing that i libri d’artista, such as those by Pizzinato and Fioroni, beckon as a future object of study.

[49] Intervista ad Andrea Zanzotto, a cura di Glenn Mott e Francesco Carbognin, «L’anello che non tiene. Journal of Modern Italian Literature», Volume 15, Numbers 1-2 (Spring-Fall 2003), pp. 61-75, p. 70.

¬ top of page